Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

Photograph © Natalie Soysa

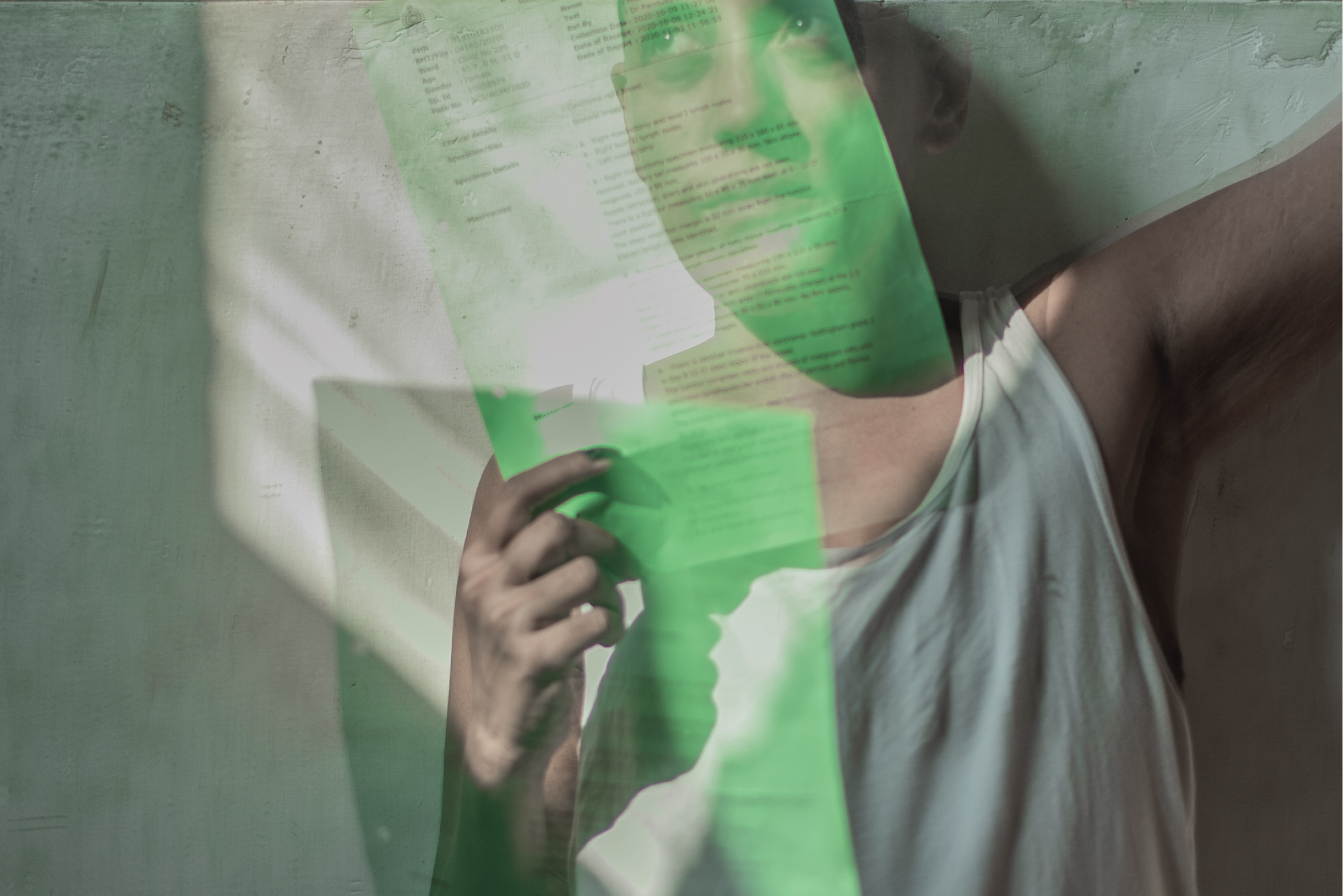

My photographic practice has involved forced confrontations with rarely documented issues like rape, abortion, gender, sexuality, sexual and reproductive rights, and how women are represented in the media. It does so by exploring the human form and giving my subjects agency as opposed to documenting bodies through a voyeuristic male gaze. It puts the unnecessarily private in a public space.

It was this very practice I leaned to when documenting my own journey this year. My own identity has been somewhat circumspect as I haven’t been able to connect with any of the labels in our lexicon. Being diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer forced me to finally confront and come to terms with my identity as my physical reality evolved from the loss of hair to the loss of my breasts, by way of clinical intervention and an evolving hormonal makeup.

Breast cancer is seen as a largely ‘private’ illness in South Asia. There is no celebratory head shaving or public seeing of someone experiencing cancer. As a result, the colossal evolution that a breast cancer patient must go through from a rapidly changing physical reality to how that reality confronts public healthcare or social encounters. This reticent mindset leaves society unprotected from breast cancer and results in many diagnoses (like my own) coming at an advanced stage. It also leaves everyone diagnosed in the region grappling for answers. We are not in the habit of regular breast checks nor are we in the habit of talking about it because we still see women’s bodies as taboo dialogs that are more suited to the pornographic than the everyday.

What began as documenting my journey to battle cancer, mutated into a journey of self-discovery. Who was I without breasts and a lower Estrogen supply? Was I in any sense really feminine merely because I presented that way for many years? Did I opt out of reconstruction because my breasts no longer corresponded with my sense of self? Being confronted with an illness, treatments, and a body that raised these questions more intensely made me feel at loggerheads with myself for a while.

Similar to Donna Haraway’s Cyborg, “a creature in a post-gender” world, I began to see myself beyond the binaries that life had set for me. Today I am grateful for cancer coming before its time. It now gives me the rest of my life with my identity finally intact.

I am mutant.

20 November