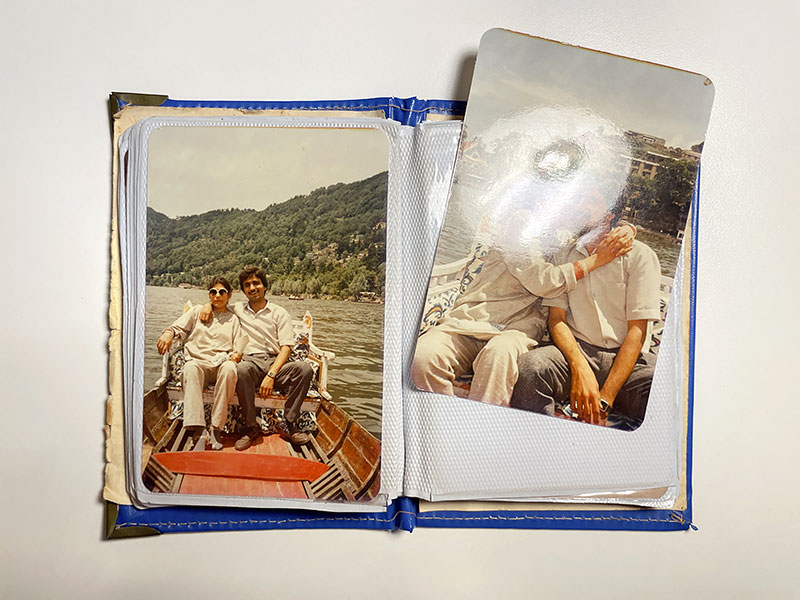

Photographer Unknown, My Parents on their Honeymoon, somewhere in Nainital, date unknown, 1990

Digital Scan, Analogue Photograph, 8.3 x 12.6cm. Courtesy of Jatin Gulati.

“… An artificial eye enables us to see ourselves – and our loved ones – as real. By positioning ourselves in relation to these photographic images, we posit ourselves in space and existence across the passage of time.”

~ Elissa Marder, Mother in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

“Myself, I saw only the referent, the desired object, the beloved body; …”

~ Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

This time around when I went home, I awaited the day my parents sat together and revisited the family albums, stored in Maa’s side of my parents’ cupboard, and wrapped in my late grandmother’s kameez printed with green, purple and ochre-yellow flowers.

I waited because photo albums, in a joint family such as mine, are shared documents: a repository of a collective’s existence, holding together individual members in the formal bounds of a book. Engaging with them solitarily, so I thought, would be a breach of long-set household conduct, and consequently could be misunderstood as a passive claim by an individual over their family’s inheritance.

So, I waited for the day Maa decided to spread out the relics of our past on her bed, as she would usually do – albums of various sizes, softened textures representing significant events of the family, and heaps of loose photographs were laid out on her bed, like faint pieces to be rejoined together and make up the life that is spent. Although some things were different this time: Maa’s hair grew thinner and was now difficult to shroud them behind the artificial black, or rather she had come to accept their fate. On the other hand, Papa’s body aged scrawny. His eyes now grieved when he smiled. Also, this time I began to consider myself carrying somewhat of a photographic sense. Consequently, I tended to observe closely their gestures and movements, the setting and action, and listened to their words carefully as we turned photographs after photographs and passed around the frayed books.

I noticed how my father gently stroked certain photographs – mostly of his mother – as if his entire being subsided in the gentleness of his touch. Intermittently he would rub his dotted cheeks, his eyes, his forehead somehow trying to shred away whatever the images were making him feel, and what we knew he was terrible at hiding. In moments, I noticed that he too was mourning. That he too feared the idea of never knowing his mother fully. And only recently did I realize how sitting with the family album alone could also be a sign of bereavement, or even misery, as goes the unsaid notion in my family. Someone who is absent or who has been lost, one tends to find their essence in these old photographs. Photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch us like the delayed rays of a star.[1] Engaging with them solitarily would be as if one is unable to live in the present, and is captivated by their loss. Looking at a photograph long enough, this way becomes almost an act of self-imprisonment. Perhaps with the company of the others, it was easier for them to remember the dead, and yet keep a sense of the present, making sure every member of the family is keeping afloat.

Meanwhile, Maa began by looking at her wedding album, which said ‘Sweet Memories’ on its maroon-velvety front, held together with strands of transparent tape and loosened stitches. Ecstatically, as always, she would introduce me to each and every relative, highlighting key instances of her wedding and allowing me to almost virtually become a part of the day that certainly changed her life.

Afterwards, she continued her engagement with an unnamed album, measuring exactly six inches by four inches, possibly the smallest of all, which at a first glance covered no significant occasion or gathering, and consisted of ordinary photographs put together from seemingly unrelated events of the family. I wondered how this came about as Maa intensely went over and over this album. Her presence now appeared more internal than before, and her voice felt too far away. In the secrecy of this album, stacked underneath the socially acceptable photographs, in one of the sections, was kept an intimate portrait of the couple sitting on a small boat in the middle of a lake. It showed Maa holding my father imitating a kiss on his cheeks. Her eyes closed, fingers interlocked, and arms gently resting around my father’s shoulder. My father looking straight into the camera, smiling. The mountains safeguarding at the back. Pulling the photograph out, she gave it a quick look, and before discreetly sliding it back under the photograph from the same event, only renditioned un-kissed, she mumbled in a now gravitated tone, “…this is something else!” and wanted to move on. As if she completely refused to identify herself with the woman in the photograph. Perhaps her role as a mother, with me being next to her stopped her from recognizing her own intimacies. Hesitatingly, she allowed me to glance over, and only briefly breaking down the otherwise indelible norms of an ideal maternal figure and the heavy pillars of patriarchy.

It was only now I realized the album in question was originally meant to be a record of my parents’ first-ever getaway after their wedding: The Honeymoon Diary! It was curious to know how an album which was initially intended to record the warmth and togetherness of a newly married couple over time gets transformed, suffused and devoured by the photographs of other members of the family. And how the now apparent honeymoon album ended up including photos of her in-laws, her children, of ritual and devotional gatherings for the family’s good fortune, and from other small events. Maybe for this very reason, couples at the first place after their wedding venture out to the higher altitudes or travel somewhere away from the domestic space, closer to nature where familial norms of relationship, intimacy, and closeness wouldn’t suffice, and love perhaps would make more sense amidst strangers.

The role of a maternal figure and in general, the subsumed place assigned to women in society is further validated by how the photographs are arranged in a family album: directing which photos to place on top and be allowed the scrutiny of others, and which need to be tucked away in the privacy of acceptable behavior within the family structure. Regulating us on how one should express love, and to whom one should be seen openly loving. Further upholding the outlined position of mothers, wives, and daughters in the hierarchy of a household. Possibly, for this very reason over the years, I too have kept secret the photos of my own love affairs, hidden in-between the pages of books, buried under cushions & bedding, and in many other recesses of my apartment. Most often it was the photographs of my mother holding a child – my elder brother or me – or posed in the formality of an Indian wife and a daughter-in-law, which were ubiquitous on the surface. It is only in the netherworld of the photo album where I could – in part – witness my mother before being confined to anything else, as a woman, as a friend, as an individual un-mothered.

The Honeymoon Diary, 2022, Digital Photograph. Courtesy of Jatin Gulati.

In certain moments that we spent with the family photographs, I observed my parents’ reactions from afar, objectively, viewed them with a sense of subtle detachment and sometimes devoid of any burden of familial relations. In these brief moments we stood together, closer, at the liminality where I became a little less of their son, and possibly they, a little less of my progenitors.

Let’s go beyond the domestic and look at the images of intimacy in the public spectrum.

Around the first week of April 2021, a photograph was circulated on various social media platforms, in which a police inspector is seen interrogating a young couple in a public space while media and passersby record the event with their cameras. What is so captivating about this rather unattractive and conventional image, with an otherwise unsophisticated visual aesthetic, and a relatively modest one when it comes to the kind of imageries we have seen of physical violence, state brutality, and the misuse of power, is perhaps the photograph’s ability to ceaselessly and plaintively deceive.

The photograph originally taken in Lucknow was first published on March 27, 2017, in an article by The Quint and other media outlets to report about the ‘Anti-Romeo Squad,’ an initiative to ‘protect the honor of women’ by the Uttar Pradesh CM Yogi Adityanath.[2] In other words, a provocation demarcating the social boundaries of love and intimate relationships. Three years later, the same image is revived, ripped off of its context, and now claims to be representing – alongside a meticulous text with communal undertones – a recent event from a public park in Noida, where the police inspector supposedly had caught hold of a Muslim boy and a Hindu girl, making an imaginary case of ‘Love Jihad.’[3] Asserting an islamophobic conspiracy theory: where the alleged hypersexual Muslim seduces, deceives, feigns love, and has motives of war of demographic and everything else that comes along with it. Religion and faith become potent subjects to read into the visual. Thereby, institutionalizing an imaginary concept in history and society merely through a revived photograph.

Certainly, a feeble case can be prepared for the resemblance between this image and Berger’s choice of the images of imperialism[4], both gestural and in terms of their function: the photograph of Ernesto Che Guevara at Vallegrande, Rembrandt’s painting of The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Nicholas Tulp, and this image of an alleged Muslim boy being investigated in a public space. The officer’s position and gestures analogous to those of the Bolivian colonel and of the Doctor; the passersby’s attention to the event transpiring; the placement of the subjects so as to interrogate, inspect and demonstrate respectively; the similarities in their function, as described by Berger to showcase a corpse (or a living corpse in this case, as someone undeserving of life, looking at the position of Muslim community in India) being formally and objectively examined; and so on and so forth.

Let’s make it clear that it would be foolish to attempt to repeat the discourse that Berger brilliantly orients us with in terms of reading a photograph. What is perhaps of immense interest here is not the similarities and resemblance, but the precise distinction between the photographs taken at least half a century apart. This is to say that the image in question, which is invariably an image of imperialism, is not what it was first meant to invoke, and has been reiterated, mishandled, perhaps manhandled and almost raped with imperial motives.

(Left) Bolivian army officers and reporters stand looking over the body of Che Guevara, October 1967

Digital Photograph. Photo: Topham Picture Library (TopFoto).

(Right) Rembrandt Van Rijn, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632

Oil on Canvas, 169.5 x 216.5cm, Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Photographer Unknown, UP Police inspector interrogating a young couple in a public space

Date unknown, Digital Photograph, Published on 27 March 2017, The Quint, PTI Archives.

It is not only the idea of the spectacular image that needs critical attention but the manipulated and morphed images of propaganda where the focus is shifting. Photographs that appear nearly harmless and insignificant at first, unlike Berger’s choice of the image of Che Guevara, perhaps because the state of propaganda has moved further, as has photography, from a single-image narrative to a web of disjointed images coming together, part by part, encapsulating the masses in a web of lies and fiction. For every one of Berger’s images of imperialism, countless such unimpressive images are unleashed in the digital sphere, navigating their invented second, third, and more lives, holding an immense amount of power and deception. These intermediary lives of the photograph invoke the birth of calculated fiction, and the contestation of the story it creates happens only after its damage is done.

The manipulated image on the web immediately goes viral, virulent, violent, frequently coming alive from the past, and plays a purposeful role before disappearing back into the abysmal database. This image which can be seen as ‘infected’ more often becomes relatable for the people than its original counterpart, resulting in the overlap of the public image with the image of the public. This is to say that it is not the honesty, but the distrust, infidelity and disbelief in photography that makes it the medium of interest and engagement.

I return to the day when past, present and future had ceased to exist progressively. I return to the moments in my parents’ room, where after half a day’s voyage, we were folding back books of lost times and began ebbing slowly to the present with heavy voids sulking in the air. “…In lives shaped by exile, emigration and relocation, such as my family’s, where relatives are dispersed and relationships scattered, photographs provide perhaps even more than usual some illusion of continuity over time and space,” writes Marianne Hirsch.[5] With this illusion of enduring past and history, I return to that precise moment, as I write this text, when I first encountered a particular photograph with the ‘stab of recognition.’ The photograph that silently lived for generations, and yet unseen for years, pressed against other photographs in an album which was exposed to its bare bones. The covers dislodged from the spine, like land carved out into two nations with a border. The blunt-edged cardboard pieces which make the covers were exposed through a thin layer of crumbled foam, hard-pressed underneath the torn and charred leather with stains of dried glue visible like the Violence that follows the Divide. Papa held the disjointed pieces together, tightly making a human spine through his veiny hand. As he went about this album, flipping backwards, my eyes met with the photographic eyes looking back at me, and there she was, my father’s-mother’s-mother’s look, which I first misread as the mother we all mourned. As Amma, my grandmother, whom we had all nursed during her prolonged sickness.

“Wait… Is this…?”

“This is…”

“This can’t be…,” I hesitated to bring out her name. Papa, understanding my couldn’t-mention reference, corrected me with a heavy tone, and annotated the woman with her almost disinterested face, situated firmly in the middle of the picture with unblinking eyes looking back at me, as his grandmother, Amma’s mother.

My heart palpitated as I heard the two words I never had imagined could be used together – “Amma’s Mother,” I repeated in my head. The tautological words, both meaning ‘mother,’ acted as two swings of a door that was opened at that moment to my family’s history which I thought had stopped at my grandmother, and synonymously at the Partition of 1947.

Family Album, 8inch x 5.5inch, 2022, Digital Photograph. Courtesy of Jatin Gulati.

Multiple mourning settles in the reading of this photograph: Amma’s mother who survived, along with her five daughters and a son, lived life longing for her home lost to the other side; at the same time, Amma herself mourned her brother who died young of cancer sitting graciously to the left; Amma’s sister-in-law, poignant to the right, who perhaps grieved her husband almost her entire married life; on the other side, six years past Amma’s parting, on this day, the onlookers of this picture, the bystanders, Papa and myself; and lastly, the baby girl on Amma’s mother’s lap in the middle, holding her father’s hand, who perhaps would have known her father only through this photograph.

The image of my grandmother’s mother had revealed my grandmother to me, for the first time, as a daughter. And her painstaking resemblance to her mother, to a person unknown – at least to me – had distanced Amma even further and seemed to have made me a stranger to her life. This in-recognition of the beloved, which is what Barthes had called, and later Hirsch explained as a prick, a jolt, a speck, a sting, a bruise, a stab, incapacitating, lacerating, a little hole, a cut, stupefaction has brought down grief all over again at the very first step of a seemingly endless ladder.

After a while, Maa knotted Amma’s kameez, appropriated as a bag, and stored the bundle of albums back in the cupboard. A few moments of silence led to the immersion of the three of us into daily errands.

Later that day, as my parents went for an evening stroll, still compelled as well as repulsed, I reached into the bundle and flicked the photograph from the album. The threads now loosened shall lead to the Sisyphean labor of understanding a photograph.

__________

[1] Roland Barthes. Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1981, p. 80-81.

[2] Meghnad Bose. In Yogi’s UP, Are Anti-Romeo’s Out to Enforce ‘Indian Morals’?, The Quint, 27Mar2017, https://www.thequint.com/news/politics/yogi-adityananath-up-anti-romeo-squads-for-harassers-or-couples-meerut-ground-report

[3] Archit Mehta. False Conspiracy About ‘Love Jihad’ in Noida Spun Based on 2017 Image from Lukhnow, AltNews, 9Apr2021, https://www.altnews.in/false-conspiracy-about-love-jihad-in-noida-spun-based-on-2017-image-from-lucknow/

[4] John Berger. Understand a Photograph, ed. Geoff Dyer. Penguin Classic, 2013, p. 3-16.

[5] Marianne Hirsch. Family Frames, Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997, p. xi.

Copyright © 2023, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Writer and visual artist with a background in architecture, Jatin Gulati’s practice is concerned with the ubiquity of the past, though most often driven by its traces in the immediate, personal and lived experiences. His interest in thinking photography stems from the role of images as myth-making for social, political, and familial ideologies. Graduated in photography from Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dhaka, his photographic work incorporates media such as photographs, text, and digital drawings. He teaches contemporary photography narratives at the School of Media, Arts & Sciences in Srishti Manipal Institute, Bangalore. He is currently based between Delhi and Bangalore.

Copyright © Jatin Gulati

Copyright © Jatin Gulati

20 November