Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

Photograph © Asim Rafiqui

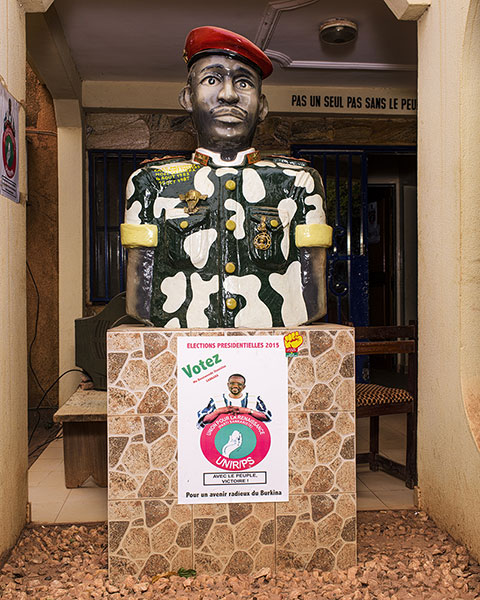

On October 31, 2014, a popular uprising toppled the twenty-seven-year dictatorship of Blaise Campaoré. And whereas mainstream media reported it as a spontaneous and unexpected development, the fact is that the rebellion resulted from decades of preparation and struggle. It was the outcome of a long history of arrogance and indifference towards the people. On that October morning, as hand-picked parliamentarians gathered at the Hôtel Indépendance to rubber-stamp Blaise Compaoré’s demand to permanently extend his 27 years in power, the people of the country came out onto the streets. A few days later, he, along with his family, was gone. The people’s uprising in Burkina Faso remains one of the most important, yet least engaged and reported, political developments in modern African history. Though not unique, it reflects the political and social changes sweeping across a continent where people speak out against exploitative and indifferent power. As Zachariah Mampilly and Adam Branch, when speaking about their recent book on African political movements titled Africa Uprising, argued in a recent interview that:

Many in Africa have lost faith in democratic elections as the solution to structural problems. Across the continent, protests have unfolded in countries spanning the democratic spectrum – often, the formal political institutions matter little in determining where protest will take place. We understand this popular disillusionment as part of a broader crisis of political legitimacy in Africa characterized by the increasing distance between state policies and popular demands.("Africa Uprising: Popular Protest and Political Change," African Arguments, online 23.Mar.2015.)

20 November