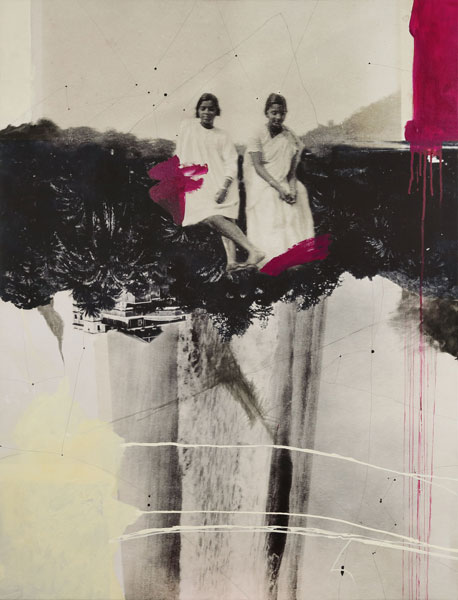

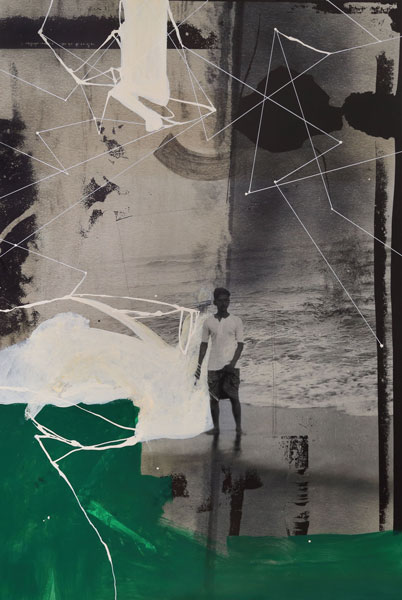

Asha Jaowa, Giclée print on canvas with acrylic and ink, 40 x 52 inches, 2023 © Sukanya Ghosh

It is often believed that memory can be both a blessing and a curse. When there is a rupture in time and the affiliations that surround it, the act of remembering is increasingly piercing. I repeatedly recall a text message from a friend post a crumbling relationship when they asked me to remember them “fondly.” With the passage of time, the memories that were once agonizing, have morphed into a bittersweet fondness that subconsciously emerges in hidden words, quiet photographs, and stray conversations.

As creative practitioners, we thrive in these nostalgic creations and destructions of worlds that sometimes fuel our practice and at other times deter it. But for multidisciplinary artist Sukanya Ghosh, the past is anything but a restriction, and instead behaves as a portal to infinite possibilities. Here, the fondness of memory is seen in biographical imaginations that are currently lining the walls of the Cymroza Art Gallery in Bombay, India. In an ongoing show titled The Parting of Ways, curated by Rahaab Allana, Ghosh creates ‘optical collages,’ using her family archives that were slated for destruction because the people in the images were often unknown.

With the layering and simultaneous unpeeling of these photographs discovered in her grandmother’s collection and various familial homes, Ghosh removes the specifics of time and place from her frames. Reality is upturned, as waterfalls emerge from beneath unknown muses, and landscapes are morphed to accommodate floating figures and drifting constellations. The viewer walks through a lucid dream, nudged by collective moments that aren’t necessarily theirs. And still, somehow, familiarity takes form in the tender cracks and missing pieces within the artworks. Is the surface of another’s memory enough to trigger our own?

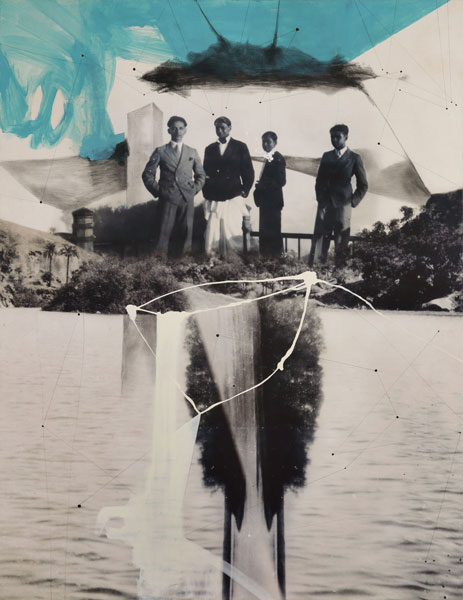

The Parting of Ways, Giclée print on canvas with acrylic and ink, 40 x 52 inches,

2023 © Sukanya Ghosh

In the essay accompanying the exhibition, Allana writes, “Perhaps the aesthetic here suggests that no matter where we locate ourselves, and whatever thresholds and interfaces we navigate, within each context our consciousness is a shifting middle world.” The artworks in the show prompt this ‘shift,’ which encourages viewers to visit their own family histories, anecdotes, and ethnographies rather subconsciously. The fragility of memory is quite evident, as Ghosh molds and melds disconnected stories to create her own universe, taking it to a place where its origin is unrecognizable but still deeply valued.

She is amused by Freud’s usage of the word unheimlich, which is used to describe the uncanny, the unfamiliar – almost absurd. “I keep coming back to it since this is precisely the feeling that I enjoy building into my works. You might see something that looks familiar, but simultaneously there is a strangeness to it,” elaborates Ghosh with a hint of mischief in her voice. I experience this firsthand, as I’m absorbed by her collage titled The Falls, which is a digital collage with archival photographs and acrylic paint that features her great grandfather and an unknown woman sitting amidst an idyllic scene engulfed by a waterfall. While the elements in the frames are completely created by the artist, I am instantly pulled towards an archival image of my own grandparents soaking in some quiet time by a gushing river in Kashmir, 1962. Funnily, it then leads me to a photograph of my great-grandparents in a similar setting from Surat in the 1920s. Much like the presence of water in these frames, memory seems to overflow.

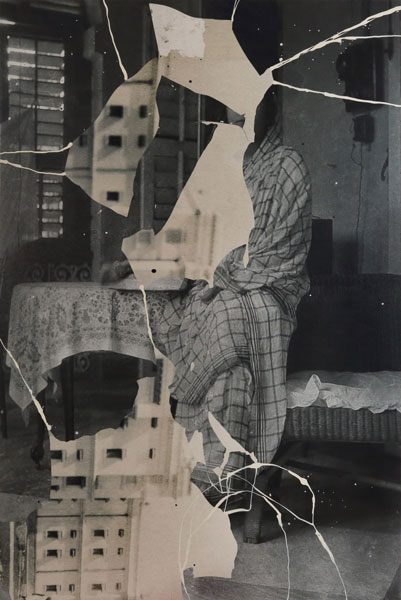

In Medias Res, Giclée print and mixed media on paper, 40 x 60 inches, 2023 © Sukanya Ghosh

In a talk which I attended between Ghosh and curator and art writer, Veeranganakumari Solanki, there is a thoughtful unravelling of the meaning behind an ‘archive,’ and this sense of formality that it holds in the artistic world. Ghosh attempts to break the weight that the archive carries and interpolates it with elements of play. She isn’t interested in the idea of nostalgia, but instead uses her interventions as an exercise in reimagining the past. “Archives are often associated with the passage of time, but they could also be what people have edited out or put together to form a family collection. In Ghosh’s practice, what was once considered a closed chapter, is an opening for change,” contemplates Solanki.

This idea of memory acting as a point of departure, draws me to a poignant passage in Sally Mann’s memoir, Hold Still. The sensitive photographer writes, “I tend to agree with the theory that if you want to keep a memory pristine, you must not call upon it too often, for each time it is revisited, you alter it irrevocably, remembering not the original impression left by experience but the last time you recalled it. With tiny differences creeping in at each cycle, the exercise of our memory does not bring us closer to the past but draws us further away.” Of course, here Ghosh is deliberately altering facts, but since it consists of people she barely knew, can it truly be seen as an act of dismantling memory or on the contrary – building upon it?

Mann also muses that “Part of the artist’s job is to make the commonplace singular, to project a different interpretation onto the conventional.” And while I’m unsure Ghosh sees it as her ‘job,’ so to speak – by using conventional family photographs and layering them with scans, digital collages, physical collages, printmaking techniques, old negatives, UV prints, animation, and reverse point-paintings – Ghosh has created an ongoing past. Allana further explains this in his writing, “Ghosh’s equivocal works juxtapose the random with the purposive, the accidental with the intentional, the coincidental with the causal, the bound with the liberated.”

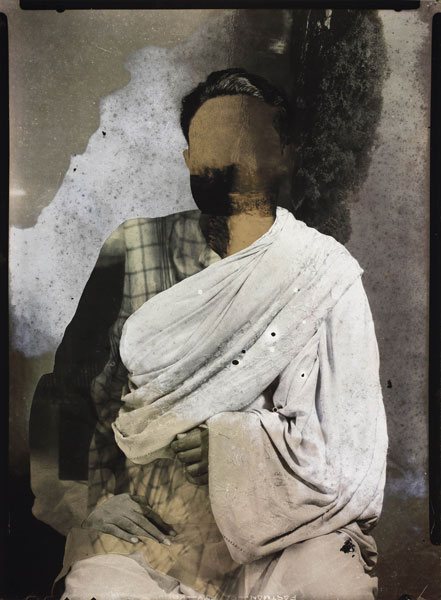

Dadubhai, Untitled, Digital collage using archival photographs, 19.5 x 26.5 inches,

Edition 1 of 6 +2 AP, 2016/23 © Sukanya Ghosh

As I move through the gallery space, the people in her images drape themselves onto the glass of the artworks opposite them, coincidentally continuing Ghosh’s techniques of overlay. It feels like a stroll through the artist’s overwhelmed mind that is a palimpsest of ancestral histories. The fragments maintain the secrecy of stories that are purely built by intuition and the distance between the artist and her archives. In his book Another Way of Telling, John Berger dissects this very aspect of artistic style and writes, “Meaning and mystery are inseparable, and neither can exist without the passing of time.” Here, the intangibility of time is the central protagonist, as Ghosh challenges herself to give it a form and structure that is legible.

Like the Stars in the Sea, Giclée print with archival photographs and mixed media,

Like the Stars in the Sea, Giclée print with archival photographs and mixed media,

40 x 60 inches, 2023 © Sukanya Ghosh

In artworks such as Jyoti, and Like the Stars in the Sea, the viewer is directly confronted by the people in the frames, who seem to blend effortlessly into their dystopian surroundings. The alternate universes seem believable because of the ease with which they stare back at you, comfortable in the geometry that encompasses them. In the exhibition essay, this thought is addressed by Allana, who writes, “The Parting of Ways then urges us to stay aware of at least one core function of the existential particle in any form: it serves as a potent reminder that we can remain satisfied with understanding the ‘part’, since the truth may well be that, despite our efforts or desires, we can never really know the ‘whole.’”

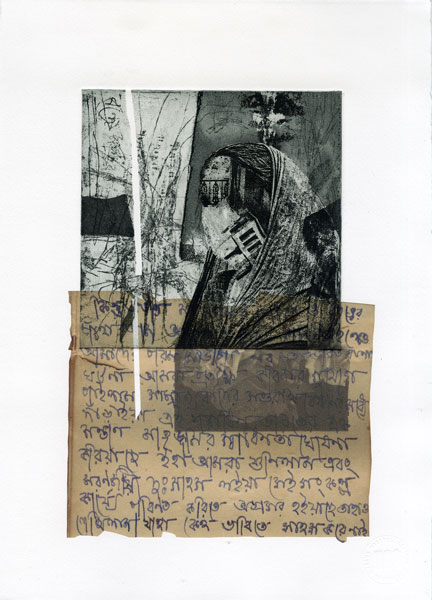

Smriti’s Dream, Soft ground etching with chine-collé on Zerkall Koperdruk, 15 x 10.4 inches,

Editions 2 of 6 +2 AP, 2023 © Sukanya Ghosh

It’s intriguing to think about how fragments from larger narratives seem so relatable, even though there is nothing to connect the viewer to the individuals in the artworks. In large portraits such as Smriti’s Dream, Binapani, and Dadubhai, Ghosh’s grandparents are the central protagonists, but are devoid of their original identity. The artist intervenes by removing the faces from the portraits and creates multidimensional worlds in the center of the gaping holes, proving that with anonymity comes relatability.

In an interview with ASAP, Ghosh says that the best part about experimenting with these images was that, in those days, there was no concept of deleting the photos or cropping someone out, or even changing the exposure. A lot of the images that she found had cracks in their negatives, accidental double exposures, and cropped heads, which only furthered her endeavor to build her own connections with the families within these photographs. Of course, she did ponder upon who was behind the camera, the purpose of the image, and the evolution of the medium over the years, but it was the excitement of the unknown that fueled her creative practice.

While the majority of Ghosh’s work stems from this concealed reality, the artist also was heavily inspired by her grandmother, Smriti, whose name in Bengali coincidentally means ‘memory.’ She was a keen collector of histories, objects, and crafts — a gene that clearly seems to have passed down to Ghosh, as well. “From her collection, emerged an elongated scrapbook with a red cover that is usually used for accounting. And amidst it I found scores of newspaper cuttings written in Bengali carefully saved!” exclaims Ghosh. At first, the articles were seemingly random, but upon closer inspection, she realized that this was her grandmother’s engagement with the freedom movement pre-independence. “It begins with Vande Matram, and then I found an excerpt that translated to ‘today there has been a declaration of independence, and it has given us a hope we never thought we’d have.’ I believe she was talking about the Quit India movement and Gandhi’s speech given at the August Kranti Maidan in 1942,” Ghosh elaborates.

This letter now finds itself juxtaposed against her grandmother’s anonymous portrait in the artwork Smriti’s Dream, that also happens to be the only work in the exhibition that has elements of text. Using a printmaking technique known as Chine Collé, the artwork almost feels like a torn page from Ghosh’s grandmother’s scrapbook, that is embedded in longing, and excerpts of Independent India’s origins. “As artists we are constantly playing around with form, but the end product is to evoke something in the reader,” continues a wistful Ghosh.

Apart from the static imagery that seems like it’s in a constant state of flux, the viewer is pleasantly surprised by the presence of a wooden cupboard sitting silently against one of the walls. A pensieve of sorts, it holds within it an animated video of random occurrences like chairs, architectural monuments, animals, people in the sea, and vast vistas, projected onto a muslin cloth. Titled A Chair Walks into a Landscape, it is Ghosh’s take on the famous joke “a man walks into a bar…” and her way of introducing a lightness within the works. Here, memories appear and vanish between the doors, ambiguous in narrative and intentionally bizarre.

In comparison, Ghosh’s artwork Breathing Stones, seems like the only obviously readable piece in the show, probably because of its contemporary reference. A blackened lung X-ray engulfs the façade of the Taj Mahal, which immediately reminds a conscious citizen of the literal pollution in the air, and pollutants of communal hate that are rapidly seeping into the fabric of our being. Ghosh says that as artists it is impossible to divorce oneself of the political environment that we’re subjected to, and her works are ‘mytho-poetic’ comments on these evolving histories. While she has been working with this style of expression since 2016, she says it is because of Allana’s important questioning that the works have found ways to sit next to one another.

The Sea Inside, Giclée print on canvas with acrylic and ink, 40 x 52 inches,

The Sea Inside, Giclée print on canvas with acrylic and ink, 40 x 52 inches,

2023 © Sukanya Ghosh

This idea of a looming dystopia inconspicuously emerges in the eponymous artwork of the show and the opposing wall which hosts the serene collage titled The Sea Inside. An elongated rectangle ominously hangs in the distance of the two artworks, breaking the quiet solitude that the water brings. Representing the cities we inhabit, a single shape shatters the calmness that possibly existed in the archival past. It reads as a subtle elucidation of growing cities acting as harbingers of chaos.

Close by, stacks of original archival images, a dictionary of names belonging to Ghosh’s grandmother, and wooden boxes which are reliquaries of a sort lie beneath a glass case. Ghosh, who is hugely influenced by German artist Joseph Beuys and American visual artist and filmmaker Joseph Cornell, uses these boxes and the objects within them as a montage to create narratives. “The story isn’t even mine; it’s about creating a tension so that the viewer can seek their own,” she explains. The multiple ancestral boxes on my own desk stare back at me while I write this – as keepers of memories, they invite me in, beckoning an intervention with a time long gone … suddenly prompting a parting of ways.

Copyright © 2023, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Zahra Amiruddin is an independent writer, photographer, and professor of photography who has been working in the field for nine years with a specialization in visual practices and contemporary art. Apart from being featured in national and international publications, her main areas of interest include ethnographic studies, astronomy, personal narratives, and family histories. She has shown her work in solo as well as group exhibitions across Greece, South Korea, Indonesia, and India and is currently developing a collaborative project with Eight Thirty, a women’s photography collective. Her work was published as the supporting text in Between Doors, a photobook about North Korea.

Copyright © Zahra Amiruddin

Copyright © Zahra Amiruddin

20 November