Calcutta, the greatest city of Romantic India, ‘Jewel of the East’ and the enigma of the world, has been graphically captured in this fascinating volume of photographs. For centuries writers have attempted to reveal the squalor and luxury, the poverty and grandiose wealth in this land of extremes. But it remained for the calculating eye of the twentieth century camera, in the hand of a skilled artist to record these ‘mysteries’ and reveal them to the outside world. There were few men in India as qualified as Clyde Waddell to accomplish the project on the following pages.[1]

A layered experience of the extreme is perhaps the strongest emotion that the Calcutta album of Technical Sergeant (T/Sgt) Joe Clyde Waddell (1915-1997) invokes in weaving a visual narrative of the city in 1946.[2] In a stylistically diverse and thematically eclectic manner, it foregrounds the momentous conditions of living and navigating the urban space, while also highlighting its historical specificities. Flipping through its pages more than half a century after its creation, viewers are alerted to the critical events that shaped the processes of political decolonization in South Asia and share Waddell’s perplexity in how unwavering disavowal of vulnerability normalized precarity. Simultaneously, the album is an ensemble of diverse visual styles and genres Waddell employed to represent the extremities that informed his encounters with the historical and the everyday. Furthermore, thinking through the album provides glimpses into material histories of the album’s production, reproduction, circulation, and reception and an opportunity to appreciate its continued affective value as a mnemonic site for the veterans of the U.S. armed forces or the GIs who served in the China-Burma-India Theatre (CBI) of World War II beginning 1942.

Waddell began his career as a photographer in 1936 with the Houston Press in Houston, Texas, during the uncertainties of the Great Depression. Subsequently, his journey as a war photographer started when enlisted as a noncommissioned officer in the Public Relations Staff of Southeast Asia Command in 1943, to serve as the personal press photographer to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Commander of the CBI. Towards the end of the war, he became the staff photographer of the Calcutta-based, short-lived war-time picture magazine Phoenix (1942-’46), in early 1945, till his return to the U.S. in late 1946. Despite his significant body of work on the CBI between 1943 and 1945, Waddell’s fame endures as a narrator of GI life through his self-published best-selling Calcutta album. Variously referred to as “A Yank’s Memories of Calcutta” or sometimes as “GIs in Calcutta,” the originally untitled trial sample album was produced in Calcutta in 1945-1946 with 74 silver gelatin prints accompanied by typed annotations for each photograph. It depicted the GIs’ everyday encounters with the city, after the war was over, when they could be tourists in the “East” on their way back home.

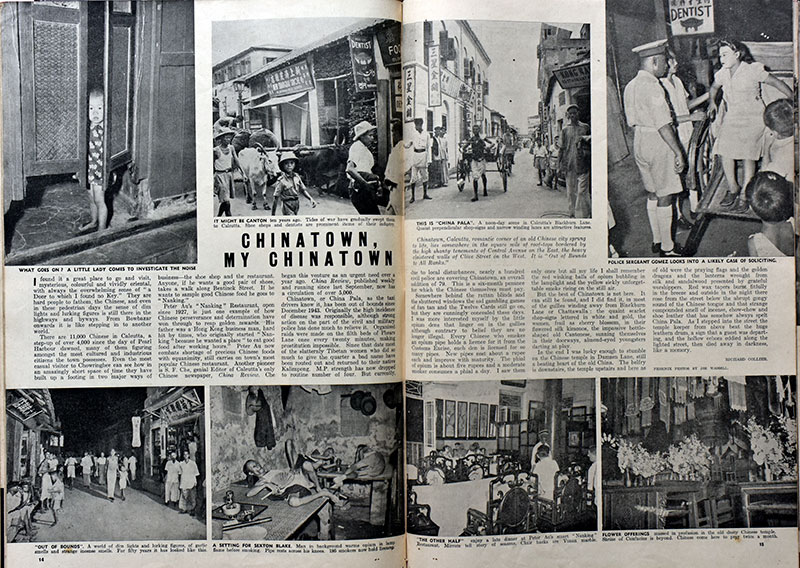

Waddell’s various engagements with the picture press and the army deeply impacted his album’s organizational schema that overlaps with the picture magazine on the one hand and the army handbook on the other. The sequencing of photographs is independent of any temporal or thematic structures usual for mid-twentieth-century official war albums. Instead, Waddell’s photographs appear as magazines would arrange some photos thematically, while interconnection between others would require some apparent stretch. Likewise, annotations for photographs shadow the military picture magazines’ long-form captions that not only provide the narrative thread to photo stories but also personalized the GI experiences in their syntax, unlike the impersonal captions for similar visual images in generic picture magazines. Waddell’s publications in Phoenix are replete with these obvious stylistic overlaps across photographs and linguistic articulations (Figure 01). However, the album allowed Waddell to be more creative and elaborate with annotations than captions for the Phoenix (Figure 02). Similarly, Waddell’s choice of subjects and the language of annotations in the album overlap with the sightseeing recommendations and life lessons provided in the U.S. Army handbooks and pamphlets like The Calcutta Key (1945), meant to familiarize GIs with the foreign land, train them in appropriate behaviors, and guide them in non-combat time to ensure “Indian civilian and police co-operation” (Figure 03).[3]

Figure 01: Richard Collier, “Chinatown, My Chinatown,” Phoenix Photos by Joe Waddell, Phoenix,

Figure 01: Richard Collier, “Chinatown, My Chinatown,” Phoenix Photos by Joe Waddell, Phoenix,

03.Aug.1945, pp. 14-15. (Courtesy: Sanjeet Chowdhury)

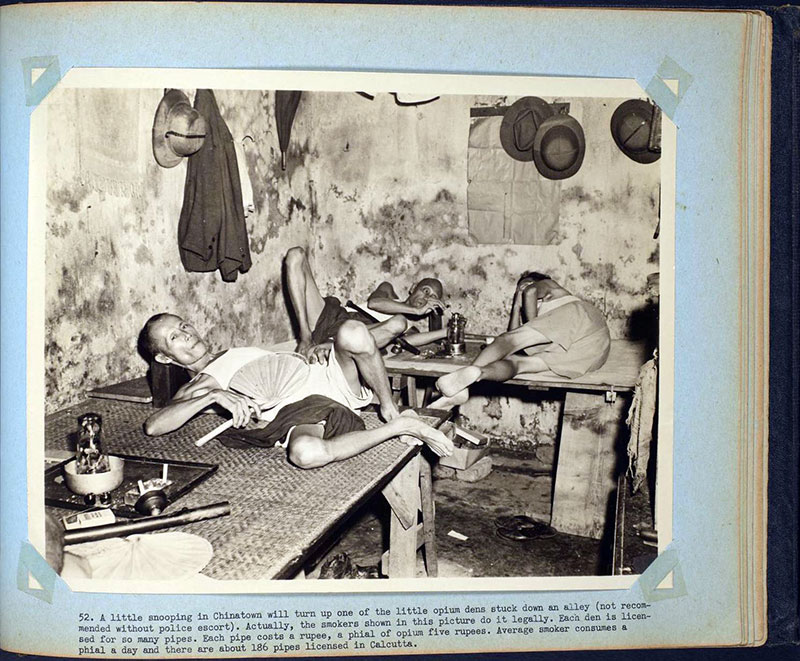

Figure 02: Photo No: 52 from Waddell’s album.

Figure 02: Photo No: 52 from Waddell’s album.

(Courtesy: Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Figure 03: Cover of the Calcutta Key (1945)

Figure 03: Cover of the Calcutta Key (1945)

(Courtesy: Andrew Whitehead)

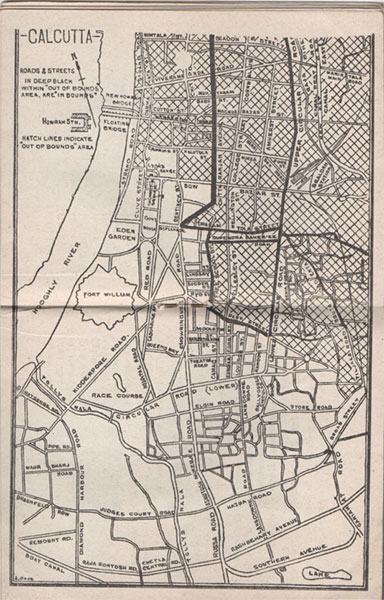

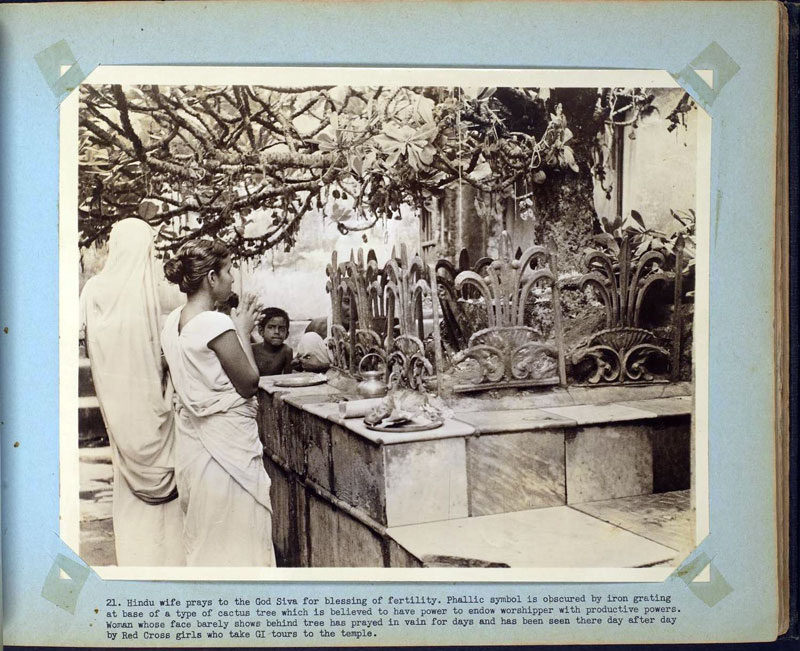

Most of Waddell’s Calcutta photographs depict sites and spaces within the boundaries of The Calcutta Key’s guide map (Figure 04) and provide a visual trace of the American Red Cross Daily Tour and places the GIs explored otherwise. For example, The Calcutta Key’s advised that the GIs could “see the Champa Tree where Hindu women come to pray when they desire sons” on the premises of the Kalighat temple was transliterated into photo no. 21 in Waddell’s album (Figure 05). It depicts the site completed with women standing in folded arms. The annotation explains the purpose of such a gesture and that any Red Cross tour would offer this sight. Alongside, Kalighat (photo nos. 20-23), photographs of other sites of organized religion like the Nakhoda Mosque (photo no. 25), the Tipu Sultan Mosque (photo no. 6), the Parasnath Jain Temple (photo nos. 19, 26), or Nimtolla burning ghat (photo no. 24) follow standard sight-seeing recommendations.

Figure 04: Guide map from the Calcutta Key (1945)

Figure 04: Guide map from the Calcutta Key (1945)

(Courtesy: Andrew Whitehead)

Figure 05: Photo No: 21 from Waddell’s album. (Courtesy: Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Figure 05: Photo No: 21 from Waddell’s album. (Courtesy: Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

However, other photographs open windows to soak in the “fascinating sights and sounds” of the city that “[e]very soldier…[would] retain [as] memories.”[4] These photographs demonstrate how the GIs followed a piece of critical advice from the U.S. Army, regardless of whether they were successful in their efforts: “Indian is different. But instead of merely noticing that difference and judging it hastily, … we …attempt to understand the fellow’s customs and ways of living.”[5] The GIs’ curiosity found ways to communicate with the Sikh taxi driver (photo no. 11), witness Indians turn “adventurous” to scale a tram car (photo no. 12), be a bystander to local law enforcement exercise (photo no. 13), taking casual interest and being “bored” by snake charmers (photo nos. 14-15), buying exotic and mundane objects in the shopping district of Hogg Market (New Market) — Grand Hotel Arcade and the Dalhousie Square (photo nos. 41-48), and engaging generally with the street crowd (photo nos. 16, 30, 32, 34, 38-40, 59). “[O]ddly dressed natives and curious vehicles” (photo no. 5), “whim” of buffalo herds on busiest streets (photo no. 10), and “snarled” Calcutta traffic (photo no. 9) provided the texture to spaces around the buildings where the GIs felt at home (photo nos. 4, 7, 8).

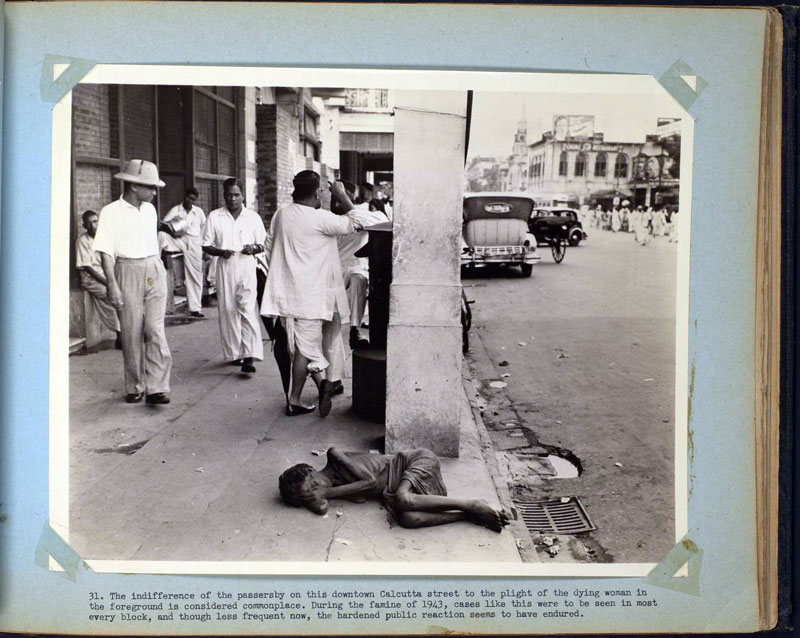

A conspicuous absence of contemporary political events in the album is predictable given the GIs were explicitly advised against discussing Indian politics during their stay. However, Waddell’s lone exception of depicting the rally of the Calcutta Tramway Workers’ Union (photo no. 32) or his comments about how the professional class was used to seeing emaciated bodies on the streets after the famine of 1943 (photo no. 31) testifies to his interest in the politics of the street and his awareness of post-war precarity, even though his album hovers around mid-twentieth-century orientalism. A focus on Calcutta’s public spaces and street life, together with insightful annotations, allow us into Waddell’s interpretations of everyday challenges and precarity. The album’s public-facing endeavor precludes diverse minority communities and their struggles beyond public sight.

The annotations routinely express his bewilderment about the resilience of people and how counter-intuitive it was for him to witness people remain impervious to empathy. Arguably, empathy fatigue in moments of overwhelming crises in the 1940s forced people experiencing them to seek refuge in oblivion and silencing that in turn helped to normalize experiences otherwise considered traumatic. With their promise of visual accuracy, Waddell’s album bears witness to a post-war extreme Calcutta characterized by this normalization that remains overshadowed by critical events like the anti-colonial political rallies, the communal clashes epitomized by the Direct Action Day of August 15, 1946, the refugee influx, and the Partition of India. Indeed, Waddell’s album is an exceptional attempt to visually chronicle the co-constitution of seemingly banal urban encounters and critical events that conditioned postcolonial India.

The nineteenth-century British imagination of Calcutta and its picturesque representation informed the GIs’ expectations and understandings without necessarily determining their mid-twentieth-century encounters. Thus, Waddell’s understanding of Calcutta was simultaneously filtered through nineteenth-century orientalist representations and 1940s conventions of documentary realism. The album embodies a unique view of the “orient” that was perceived as exotic but not necessarily esoteric or mysterious in the way it was perceived across the north Atlantic before the war. Both Waddell’s use of the word mystery in the album and Preston’s reuse of the word in scare quotes is instructive in gleaning their skepticism about the idea of India as mysterious and beyond comprehension.

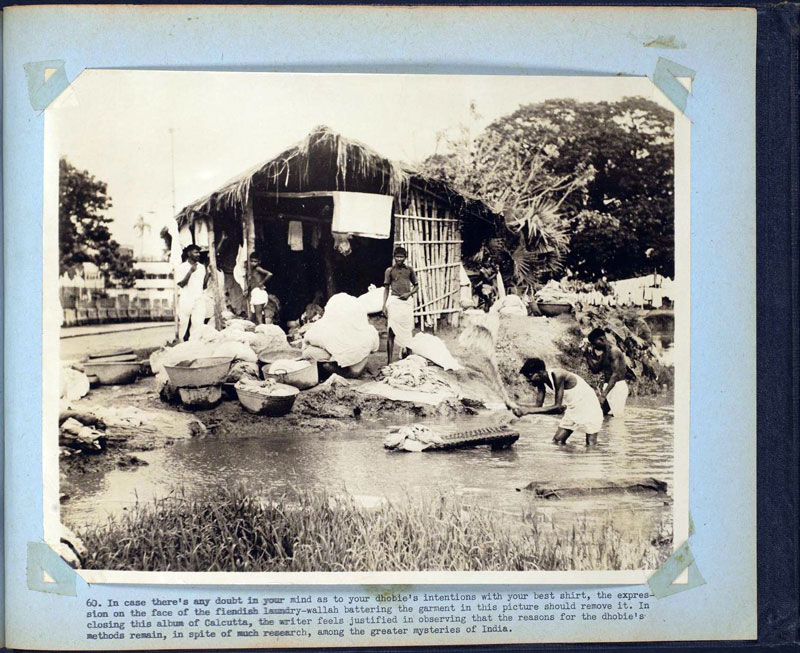

Consequently, the album demonstrates diverse representational styles including the Victorian ideal of the picturesque, colonial anthropology’s fixating gaze, early twentieth-century snapshot aesthetic, and 1940s street photography. The annotation in the picture of dhobi-s washing clothes (photo no. 60), foregrounds the “great mysteries of India,” as if to render orientalist exotica an axiomatic truth, but with a pinch of salt that would color the imagination of the veterans long after they had left India (Figure 06). Likewise, Waddell’s aerial views (photo nos. 01-03) and longshots (photo nos. 4, 6, 8, 9, 10) of the riverbank and the Esplanade / Chowringhree remind of Bourne and Shepherd Studio’s late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century ariel views and longshots of the city’s shipyard, riverbank, and the Esplanade area.

Figure 06: Photo No: 60 from Waddell’s album.

Figure 06: Photo No: 60 from Waddell’s album.

(Courtesy: Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

The snapshot aesthetic and the genre of street photography lends to Waddell’s representation of the “land of extreme” that veteran Preston remembered years later. Extreme thematic contrasts are reflected in individual photographs and when seen in pairs. For example, photo no. 31 (Figure 07) in the album depicts an emaciated human body in a busy Calcutta street near St. Andrew’s Church, with formally dressed men and motor cars in the foreground. The annotation highlights the contrast and how the 1943 famine normalized dying on the streets of Calcutta. The pair of photo nos. 27 and 28 reveal the extreme disparity of wealth and living conditions, where the former depicts relatively wealthy film actors, and the latter depicts the struggles of a young mother to feed her child. Likewise, photo nos. 17 and 18 respectively image a magician and a mad man, while photo nos. 29 and 30 draw attention to the famous and wealthy nineteenth-century mansion Marble Palace and serpentine queues of poor men and young boys waiting long hours to get their cooking fuel. The grand structure of the Howrah Bridge (photo no. 33) and the magnificent building of the Howrah Railway Terminal (photo no. 37) is followed by groups of helpless travelers waiting and living in the station (photo no. 38, 39).

Figure 07: Photo No: 31 from Waddell’s album.

Figure 07: Photo No: 31 from Waddell’s album.

(Courtesy: Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

The thematic contrast in the album is accentuated by Waddell’s active investment in representing disparate life situations. For example, the image of a group of homeless men (photo no. 51) or the dying woman (photo no. 31) is stark opposite to all urban pleasures and wealth the GIs witnessed. The photographs of the railway and waterway hubs of the city (photo nos. 02, 33, 35-40) alongside the buses, tram cars, and motorcars (photo nos. 09, 11, 12, 18) remain a contrast to the hand-pulled rickshaws, carts, horse-drawn carriages, and country boats (photo nos. 05, 09, 35, 49). Likewise, the financial hub around the Calcutta Stock Exchange (photo no. 34) complements the wholesale bazaars (photo no. 59) and street vendors (photo nos. 54-58). The Chinese opium den (Figure 02) and the “out-of-bound” female company (photo nos. 49, 53) revealed Calcutta’s “forbidden” pleasures.

As a visual form, the album is an invaluable contribution to visualizing the post-war city and the everyday lives during India’s political decolonization. As an object, it is a relic to reflect on the intertwined relationship between photography, materiality, and memory. In crafting his album, Waddell specified the material particularities of the production process in the opening page-cum-advertisement to separate it from his work as an Army employee: “[a]lbum has been prepared by photographer while on leave, using personally owned films, bulbs and paper. Laboratory work was done in a private laboratory and Indian assistants were paid for their work.”[6] Simultaneously, this statement asserted his copyright and reproduction right on the album. The trial version also contained pricing, quality, and shipping logistics. Priced at a whopping 100 rupees, the wait time for delivery in the U.S. was at least six months, allowing a “safe margin” for Waddell to return and make the final albums. He refused delivery in India during his stay or afterward because of the “[s]hortage of paper, material, slow methods and lack of time and insufficient laboratory personnel.”[7] Most known later versions of the album now in institutional collections or formally auctioned through agencies do not carry this opening page. Additionally, they have only 60 photographs, all 8 x 10 1/8 inches, out of an intended 74 photographs.

Waddell’s photographs were meant to resonate with his colleagues who experienced the immediate contexts and the eternal “mysteries” that India offered. The photographs together with their annotations stood in for a generalized CBI experience as Waddell’s close associate and war veteran M. Chas. Preston later situates them simultaneously within historical specificities of mid-twentieth century camera cultures and a long lineage of visually representing the city. Preston recollected that “[Waddell] took these pictures primarily at the behest of many friends who had been constantly asking him for Calcutta scenes.” He added that “[b]y the time he completed this project…he was flooded with requests from Americans and Britishers for copies of his photographs.”[8] In order to cater to the staggering demand, “…Waddell felt compelled to make the album more generally available through fellow GI agents.”[9]

Thus, alongside its subjects, styles, and histories, Waddell’s Calcutta album offers a rare occasion to analyze what the returning GIs took back as a souvenir and how it became a memorial site considered essential for reproduction in the CBI commemorative volume published on 1998 in active collaboration with the China Burma India Veterans Association (CBIVA). In the vast network of war albums, Waddell’s album remains unique in how it attained a continued life of enduring value to the veterans and their families “to pass down to children and grandchildren… [as it] …preserves the past and is a legacy for the future generations.”[10]

_______________

Regarding Photo References: For references to specific photographs beginning with “photo no” please see Waddell’s album. http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9949134203503681

[1] M. Chas. Preston in Robert James Kadel, ed. (1998), “Where I Came In– ” in China, Burma, India, Nashville: Turner Publishing Company. Vol 2, 97.

[2] See Ms. Coll. 802., Kislak Center for Special Collections, University of Pennsylvania. http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9949134203503681 Accessed 23.May.2022. Subsequent reference to specific photographs matches the photo number in this version of the album.

[3] The Calcutta Key (1945), Prepared by Services of Supply Base Section Two, Information and Education Branch, United States Army Forces in India-Burma.; emphasis in original.

[4] See annotation in Waddell’s album. Ms. Coll. 802., Kislak Center for Special Collections, University of Pennsylvania. http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9949134203503681 Accessed 23.May.2022.

[5] The Calcutta Key (1945), Prepared by Services of Supply Base Section Two, Information and Education Branch, United States Army Forces in India-Burma.

[6] Information printed on the opening page of Clyde Waddell’s sample album (1945-1946).

[7] Information printed on the opening page of Clyde Waddell’s sample album (1945-1946)

[8] M. Chas. Preston in Robert James Kadel, ed. (1998), “Where I Came In– ” in China, Burma, India, Nashville: Turner Publishing Company. Vol 2.

[9] M. Chas. Preston in Robert James Kadel, ed. (1998), “Where I Came In– ” in China, Burma, India, Nashville: Turner Publishing Company. Vol 2.

[10] Publisher’s note in M. Chas. Preston in Robert James Kadel, ed. (1998), “Where I Came In– ” in China, Burma, India, Nashville: Turner Publishing Company. Vol 2.

Copyright © 2023, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Ranu Roychoudhuri is Assistant Professor and Program Chair of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Arts and Sciences, Ahmedabad University. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary art in South Asia with emphasis on photography, print history, intellectual histories of art, art historiography, and postcolonial studies. She has published in peer-reviewed journals, edited volumes, art magazines, and art portals and her research has been supported by the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art (FICA), Yale Institute of Sacred Music, and several centers at The University of Chicago from where she received her doctoral degree. She curated a major show on nineteenth-century British studios Bourne & Shepherd and Johnston & Hoffman at the Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata and taught in the U.S. and Indian higher education institutions.

Copyright © Ranu Roychoudhuri

Copyright © Ranu Roychoudhuri

20 November