But for the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, representation to reality, appearance to essence, …truth is considered profane, and only illusion is sacred. Sacredness is in fact held to be enhanced in proportion as truth decreases and illusion increases, so that the highest degree of illusion comes to be seen as the highest degree of sacredness.

– Feuerbach, Preface to the Second Edition of The Essence of Christianity

When photographers attempt at describing the act of taking a picture, the often-abused word is capture. For example, “Oh! I captured that beautiful sunset,” or “I captured the moment.” But to capture, is it not to seize, to take into one’s possession or control by force? In astronomy, the word communicates an act of bringing (a less massive body) “permanently within its gravitational influence.” A seemingly harmless word, yet rampantly thrown around to perhaps communicate the machismo of the taker, to presumably having “accurately recorded something in words or pictures” oblivious to the implicitly laden power in that word. It is colonial. It is invasive.

As South Asian practitioners of photography / lens-based approaches, if we are to begin the process of decolonization of our practices in pursuit of a native idiom (or not, and certainly not a singular one), the journey has to begin with freeing our mind from the enslavement of preconceived notions sermonized by the prophets of the modernist (and post-modernist) world. To do away with such words (or attempt to) could be a step. This reflective act of questioning our adoption of language (and thus, intent), then, is political. One can enslave the body, but can the camera represent someone’s state of mind and feelings? Can it forge understanding (to evoke empathy) by bridging the insider-outsider gulf? Can the medium (inherently voyeuristic) aid in obliterating otherness by finding means beyond the cliched tropes of materiality of the body? In the post-medium world (post 1960s), where do we go from here? The fundamental function of photography in the first place, cries to be questioned in today’s ecosystem governed by an unholy triad between capitalist forces, a pseudo-secular State apparatus and a subservient media dead-set on feeding us only illusions and occasional breadcrumbs.

The widely established photojournalistic and documentary photographic practice formerly tied to the pursuit of truth and representation of “facts in an unmediated manner” – by indiscriminately resorting to spectacle – has mined citizens of their last reserves of empathy. The Press accomplished this through prolonged overexposure to descriptive and often mindlessly shocking images of violence, gore, and suffering to further amplify spectacle and rhetoric, or by filling pages with lavishly sanitized images of the affluent, a deceptively effective strategy to waylay the masses. It has caused compassion fatigue and a distancing from real life by seducing citizens to live behind decadent chambers of material aspirations. Guy Debord in his 1960s seminal book The Society of the Spectacle [1] argued, “In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.”

A linear perception of reality has for long kept the former practices stunted by an unimaginative and often trite regurgitation of age-old tropes. This lethargy has come at a cost. The perception of reality is influenced by our race, gender, caste, class, religious, and political beliefs (festering biases and prejudices) as well as real-time experiences, thereby widening (or bridging) the perceptive gulf vis-à-vis lived-life and representations. Time then demands that artists question, “What is reality?”

Amitav Ghosh in The Great Derangement, an incisive scholarship confronting the handling of climate change in literature and art writes, “When future generations look back upon the Great Derangement they will certainly blame the leaders and politicians of this time for their failure to address the climate crisis. But they may well hold artists and writers equally culpable – for the imagining of possibilities is not, after all, the job of politicians and bureaucrats.”

Conceptual photography, an umbrella term used to encompass diverse and often heterogenous approaches adopted to communicate an idea (over mere transmission of information) has also witnessed diverse explorations including proto-conceptual [2] and post-conceptual practices of the ’60s and ’70s. It comprised aesthetic vs. anti-aesthetic practices of postmodern appropriations. The genesis of such approaches lies in the provocations and inner dilemmas artists encountered at the hands of emerging socio-political and cultural shifts of their time and space, just the same way living artists (some) are responding to today’s autocratic political dispensations and decadent consumerism. But the well-intentioned artist as an ethnographer of their time and space must also be questioned for their quasi-anthropological [3] pursuits lending voice to the causes of the exploited proletariat (it is here, that I question the self as well).

But “Is conceptual by its very nature decolonizing the image?” Ravi Agarwal, over an email conversation, threw me in the deep with this question. Serving reductive answers would be puerile, and so I can only take his provocation to guide my journey. Post-humanities scholar Eduardo Kohn in How Forests Think guides our hand here, “… we have treated humans as exceptional – and thus as fundamentally separate from the rest of the world. The first step toward understanding [how forests think] is to discard our received ideas about what it means to represent something.” The process of decolonizing an image then, perhaps begins with freeing our minds from the afflictions accumulated over living in a hyper-commodified time and believing in the widely propagated illusions coupled with the willingness for sharing agency with the communities we aspire to represent, thus leveling power dynamics between the taker-maker and the subject, as a starting point.

Non-representational artworks, on the other hand, freed from the expectations of speaking truth to power can be an easy cop out of one’s socio-political obligations, though not necessarily cultural ones. And that is okay, for art must also be for art’s sake. On the other hand, there is a burgeoning rise in staged and constructed photography that are aping styles without a deeper inquiry. While such responses might benefit from momentarily riding the wave at best, they will eventually find themselves relegated to oblivion once the dust settles.

The days of the 20th century decisive moment [4] (a phrase coined by Henri Cartier-Bresson) in today’s 21st century post-modern post-truth world, if not gone, is heavily contested. The notion of a singular truth is reductive. Several photographers and lens-based artists from the Indian sub-continent, have been challenging this singularity through their pluralistic practices. The formerly fixed ideas of photography in modern India have been countered by the likes of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, Sheeba Chhachhi, Pushpamala N., Ravi Agarwal, Annu P. Matthew, Diwan Manna, Dayanita Singh, Gauri Gill etc. They picked up the cudgels and paved a path when this singularity was being vehemently enforced by its gatekeepers.

In this editorial (Against Capturing) on conceptual photography, three contemporary artists, Prajakta Potnis, Ravi Agarwal, and Soumya Sankar Bose, share essays unpacking their practice – to present an argument in favor of communicating ideas as central to their photographic endeavor. Agarwal, an interdisciplinary artist, does this with an enviable ease in his essay, The Entangled Image, where he places himself before the camera, yet situates himself into a mortified corpse in Immersion / Emergence (2006). Potnis’s microscopic gaze in her essay, In the Quest of an Undiscovered Location, upturns the way we perceive reality. She segues through cold mechanical contraptions like the refrigerator in Capsule (2012) or Porous Walls (2008) to present before us what ‘cannot be seen’ thus countering, ‘What is reality?’ I have a hunch that her insightful gaze is aided by her female gaze. Bose, in his essay, Where an Improbable Reality Meets Fiction, on the other hand, with an admirable earnestness reveals the aesthetic and storytelling strategies he adopts to tackle the tensions between reality and fiction as well as traversing between the past and present. Each of them confronts our gaze.

David Campany (my professor) in his essay, Safety in Numbness: Some remarks on the problems of ‘Late Photography’ writes, “The photograph can be an aid to memory, but it can also become an obstacle that blocks access to the understanding of the past. It can paralyze the personal and political ability to think beyond the image in the always fraught project of remembrance…” [5] Each of the three artists do not propagate the idea of the singular moment, but rather offer cultural markers where, sometimes, the image becomes trace elements and the questions central. They refuse to serve readymade answers. Yet, their works ironically find an ideal environment (usually) within these white cube spaces; a tension, that demands further probing.

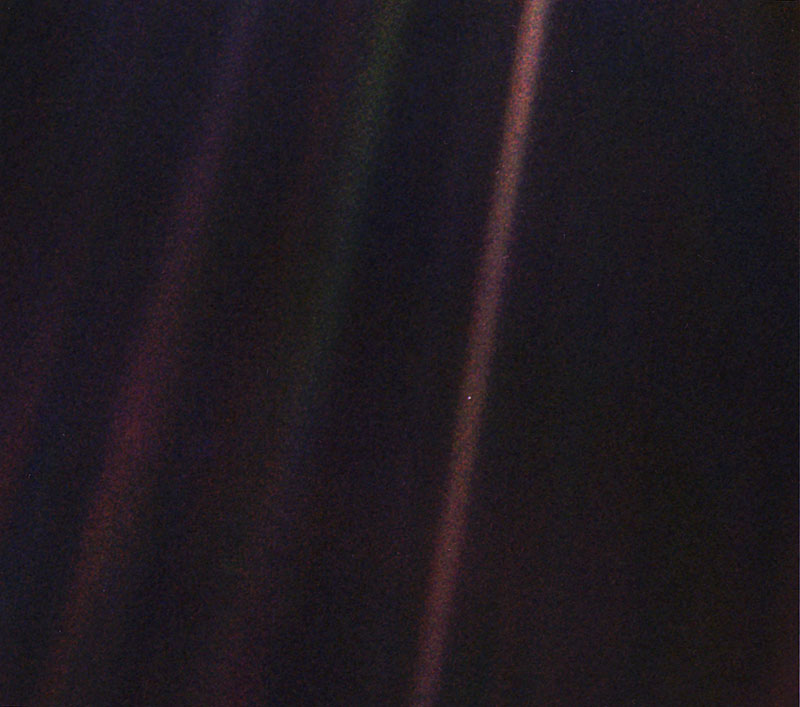

In 1977, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory launched the Voyager Interstellar Mission, a space probe to study the solar system, and finally, the interstellar space. It carried the Voyager Golden Record [6] a compilation of messages recorded in 55 languages, sounds from nature, and 115 images intended to communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials, should we ever encounter one. When the spacecraft was about to exit the solar system three years later, Dr. Carl Sagan (heading the Golden Record committee) proposed that the Voyager be turned around to take “one last picture of the Earth.” He acknowledged that such a picture would not have much scientific value as the Earth would appear too small for Voyager’s cameras to make out any detail, but it would be meaningful as a perspective on humanity’s place in the universe. The permissions took a decade to arrive, and finally, before departing the Solar System on February 14, 1990, the Voyager-I (from six billion kilometers away) turned back one last time to take a picture of the Earth – a Pale Blue Dot [7] – smaller than the size of a pixel. It serves as a portent reminder that we are a tiny fragment of dust suspended in an endless time-space continuum. In Cosmos (1981), Sagan wrote, “We are like butterflies who flutter for a day and think it is forever.” T. H. Huxley in 1887 left behind a similar poignant reminder, “The known is finite, the unknown infinite; intellectually we stand on an islet in the midst of an illimitable ocean of inexplicability. Our business in every generation is to reclaim a little more land…”

I wonder then, after 182-odd years of the existence of photography and us going around the world playing the image-warfare game, where does photography go from here? To answer this, let us teleport ourselves a century into the future, halt, turn back, and look at the visual trail we would have left. In that infinite black hole of imagery, will it look like shadows expunged out of a monstrous photocopier, or will we sight something that resisted being tamed?

Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

___________

[1] https://libcom.org/files/The%20Society%20of%20the%20Spectacle%20Annotated%20Edition.pdf

[2] Proto-conceptual: An art movement that pre-dated and paved the way for Conceptual Art, Pop Art, and Minimal Art premised on the notion that an artist can communicate with the viewer through the power of abstract forms. The term is often used to describe the early work of artists like Yves Klein and Piero Manzoni.

[3] Read The Artist as Ethnographer? by Hal Foster

[4] In 1952, Cartier-Bresson published Images à la Sauvette, which roughly translates as “images on the run” or “stolen images.” The English title of the book, The Decisive Moment, was chosen by publisher Dick Simon of Simon and Schuster. In his preface to the book of 126 photographs from around the world, Cartier-Bresson cites the 17th century Cardinal de Retz who said, “Il n’y a rien dans ce monde qui n’ait un moment decisif” – “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.” Bresson wrote, “I kept walking the streets, high-strung, and eager to snap scenes of convincing reality, but mainly I wanted to capture the quintessence of the phenomenon in a single image. Photographing, for me, is instant drawing, and the secret is to forget you are carrying a camera.” Source: http://truecenterpublishing.com/photopsy/decisive_moment.htm

[5] Safety in Numbness: Some remarks on the problems of ‘Late Photography’ by David Campany, Photoworks/Photoforum, 2003

[7] Pale Blue Dot

Copyright © 2022, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Guest Editor

PhotoSouthAsia is honored to welcome Sharbendu De as Guest Editor. Here De introduces his selected topic, which is addressed by his team of invited essayists:

Prajakta Potnis: In the Quest of an Undiscovered Location

Ravi Agarwal: The Entangled Image

Soumya Sankar Bose: Where an Improbable Reality Meets Fiction

Photograph © Imran Kokiloo

Photograph © Imran Kokiloo

Sharbendu De is a lens-based artist, academic, and writer. He has an MA in Photojournalism from the University of Westminster, London (2010), and a Post-Graduate Diploma in Journalism from the Indian Institute of Mass Communication (2004), New Delhi. He has been teaching photography and visual communications for a decade across AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi University, and Sri Aurobindo Centre for Art & Communication in New Delhi. De made pedagogical interventions by redesigning photography syllabuses and introducing visual communications courses (at SACAC). Straddling between the worlds of academia and art practice, De is constantly challenging the postulations of the other (and the self).

A recipient of multiple grants from the India Foundation for the Arts, Lucie Foundation, Prince Claus Fund, and ASEF, he has exhibited across PhEST (Italy), FORMAT (UK), Serendipity Arts Festival (India), Photo Kathmandu (Nepal), Voies Off Awards (Arles), Vadehra Art Gallery, Shrine Empire Gallery, and Goethe-Institut (Mumbai & Delhi), among others. Feature Shoot recognized De as an Emerging Photographer of the Year (2018) and he was shortlisted for Lucie Foundation’s Emerging Artist of the Year Scholarship. In 2019, he was shortlisted for Lensculture Visual Storytelling Awards (2019) among other nominations. His latest series is An Elegy for Ecology (2016-2022), a futuristic piece about human survival in a post-climate catastrophic world, which is supported by the MurthyNAYAK Foundation and KHOJ.

20 November