On November 25, 2019, hundreds of women gathered around the Chilean capital of Santiago to denounce gendered violence. It was International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Pumping their fists up in the air, they declared with one voice, “¡Y la culpa no era mía, ni dónde estaba ni cómo vestía!” (And it was not my fault, or where I was, or how I was dressed!) declaring, “¡El violador eres tú!” (The rapist is you!) The protest “Un Violador en tu camino,”[1] (a rapist on your way) went viral around the world, for two key reasons: Firstly (and sadly), violence against women is a global phenomenon, and thus the protest slogan struck a chord with women from across cultures, languages, and nationalities who found in the song a vehicle to channel their frustration and rage – for having to live under continued male oppression, misogyny, and violence. Secondly, Lastesis, the feminist collective behind the protest, ingeniously devised performance-protest as a means to translate complex feminist theories to the public, a medium far more easily relatable for the masses than having to endure academic parlance.

Protest songs with stirring music and socially conscious lyrics that had emerged from within the New Song Movement in Chile in the 1960s, and likewise Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), gave the world musical anthems which became songs of protests and resistance against oppression and injustice. They transcend borders, and return decades later, to reignite hearts and minds of the masses fueling citizens’ movements. Emerging from within a local context, musical and poetic forms, in particular, have often acquired universal currency.

The Bengali song, “Ei roko, prithibir gari ta thamao,” meaning “Hey, stop the wheels of this Earth,” written and sung four decades ago, in 1978, by the composer, poet, lyricist, and singer Salil Chowdhury, fans similar embers. I enclose a loose translation below.

Using metaphors and allusions as its leitmotif, the song sounds providential for today’s politically fanned right-wing emergent culture, and even the planetary conditions with man as its core architect.

In The Climate of History: Four Thesis[2] (The University of Chicago, 2008), Dipesh Chakraborty wrote, “Man has finally become a geological agent on the planet through its sheer number and burning of fossil fuels thus acting as a major determinant of the environment of the planet” thus severely impacting earth’s geological patterns and accelerating climate catastrophic occurrences including air pollution, global warming, glacial ice-melting, crop failures, distress migration etc, followed by Solastalgia, Dysthymia and eco-anxiety as the impending psychological aftereffects in the Anthropocene. In his latest illuminating book, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age,[3] (Primus Books, 2021), Chakrabarty points towards the deep epistemic and philosophical chasms that exist between the worldly and the planetary. The current crisis of climate change, he argues, calls for viewing the two together – the human-centric world that we have created for ourselves and the planetary, in which the human is only an incidental presence – in order to seriously confront the challenges that climate change poses (Elangovan, 2021).[4]

The latest IPCC Sixth Assessment Report 2021[5] reconfirms the same with an alarming caution: “The past five years have been the hottest on record since 1850. Temperatures are likely to reach 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2040 and the rate of sea-level rise has nearly tripled compared with 1901-1971.” Carbon Brief (2018) in “The Impacts of Climate Change at 1.5°C and Beyond”[6] report points that the population facing at least one extreme heatwave every 20 years at 1.5°C will increase from 14 to 37 percent. This means more than double the population affected today, will be in distress. It also means an accelerated rate of heat waves, glacial ice-melting – which in turn will lead to flooding and submergence of coastal areas, species extinctions, crop failures, and high mortality among the human race to name a few. In short, prolonged and sustained mayhem and pandemic.

With regard to coping with global warming, individual citizens, for instance, are making micro-adjustments like introducing sun blockers on their balconies, insulating walls and double-glazed windows, adding air conditioners and coolers, bringing more plants indoors, as well as altering their food and fashion choices. This, however, is a class-specific response of the privileged. Not stepping out into the incinerating cauldron is another option, but again, for those privileged few while the state is largely busy de-notifying tribal and densely forested reserved lands and selling them off to capitalist entities following the GDP-centric development paradigm. Increasing nighttime temperatures, however, has not yet received much attention.

A recent New York Times article, “Why Record-Breaking Overnight Temperatures are so Concerning”[7] opens with, “Last month was the hottest June on record in North America, with more than 1,200 daily temperature records broken in the final week alone. But overlooked in much of the coverage were an even greater number of daily records set by a different – and potentially more dangerous – measure of extreme heat: overnight temperatures.” “How does it matter?” many may ask. The authors explain, “Unusually hot summer nights can lead to a significant number of deaths because they take away people’s ability to cool down from the day’s heat.” Our bodies need to cool off, something that is usually done during sleep at night. But a sudden rise in temperatures, coupled with increased humidity, traps the heat, thus refusing to let bodies cool off, thereby increasing risks of strokes etc, by adding to the physiological stress. Aatish Bhatia and Winston Choi-Schagrin, authors of the article, interviewed Alexander Gershunov, a research meteorologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, “As temperatures rise, the air can hold more moisture. Water vapor accounts for around 85 percent of the greenhouse effect. The water vapor doesn’t cause the initial warming, but there’s a feedback loop: higher temperatures increase moisture in the air, and more moisture traps more heat close to the ground’s surface, like a blanket, which leads to more warming.” A combination of extreme heat and humidity can be lethal.

Does art, and photography in particular, have a role to galvanize citizens of the world into collective (reflection and) action, or is its mere function to make archival records for posterity (should there even be one)? In parts, both. Art does have that strange ability to speak truth to power. But not without caveats and a minefield to navigate.

Artistic responses to climate change (and thus our extinction) in the postcolonial postmodern 21st century have encountered a unique problem – one of disbelief. Noted novelist Amitav Ghosh, in The Great Derangement[8] (2016, Penguin), writes with searing insight, “The problem of climate crisis despite being the biggest threat to human existence today is still not accepted as a reality when portrayed through cinema or literature.” Difficult to be accepted as reality, they are reduced to genres such as science-fiction and climate-fiction, commonly referred to as sci-fi and cli-fi. We must agree that potential solutions to successfully appropriate visual art[9] to tackle climate change and environmental concerns cannot arrive as long as we continue to borrow ideas solely from the canon of the humanities discipline – for it has celebrated man as the exception and sole subject of deliberations, provocations, and ideations – arguably the pivotal philosophy that has led us on this perilous path to self-extinction. Answers must then be sought elsewhere. I shall expand upon this in a moment, but first, let us tackle the predicament Ghosh has thrown at us – this incomprehension between art and climate change.

Margaret Atwood, averse to labelling her works as science fiction, favored “speculative fiction” instead. In The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake in Context,[10] she explains, “the distinction between science fiction proper – for me, this label denotes books with things in them we can’t yet do or begin to do, talking beings we can never meet, and places we can’t go – and speculative fiction, which employs the means already more or less to hand, and takes place on Planet Earth.” Most sci-fi and cli-fi works narrate doomsday in an unforeseeable catastrophic future as a result of apocalyptic events of unfathomable proportions, thereby reducing them to a spectacle. The American poet and essayist, Elisa Gabbert, examining disaster-culture and its representation in The Unreality of Memory[11] (Atlantic Books, 2020) notes, “We do learn from the past, but we can’t learn from disasters we can’t even conceive of.” She adds, “It’s the spectacle that makes a disaster a disaster.” News, especially the 24/7 television news culture, turns events, and thus disasters into spectacles (through unhinged over-the-top sensationalistic visual styles) by playing them in our living & bedrooms on an endless loop, thus amplifying the event’s shock value. She adds, “Disasters are news because they are news” calling us to then examine the nature of news, its production-consumption culture and implicit politics shaping them. “Horror and awe are not incompatible; they are intertwined.”

Narratives of apocalyptic doomsday, today, as a strategy to shock or guilt the viewer to metamorphose into climate activists or conscientious citizens to switch off our air conditioners and cars, is an ineffective ritual. Susan Sontag in AIDS and Its Metaphors[12] wrote, “With the inflation of apocalyptic rhetoric has come the increasing unreality of the apocalypse. A permanent modern scenario: apocalypse looms…and it doesn’t occur. And it still looms.” Besides, shock and sensationalism as visual strategies, largely the provenance of photojournalism and classic documentary photography, have led to numbness and compassion fatigue (Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003). Allan Sekula in Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary writes, “Documentary has amassed mountains of evidence. And yet, in this pictorial presentation of scientific and legalistic ‘fact,’ the genre has simultaneously contributed much to spectacle, to retinal excitation, to voyeurism, to terror, envy and nostalgia, and only a little to the critical understanding of the social world.”[13]

We no longer live in a world of utopias given the material and cultural reality of the world we inhabit; narratology has largely shifted base to its “evil twin,” (Atwood, 2003) the dystopia. Artistic responses to climate change have very much been swung over to break bread (and bed) with this evil twin. This, in turn, feeds shock and sensationalism into modern news culture, weaving myriad tales of doomsdays by often using the grotesque in cinema and photography, thus further raising psychological walls built of numbness, apathy, and compassion fatigue. This has depleted our ability for compassion and empathy towards the people represented; for they have been turned into a spectacle for passive consumption by the audiences. This vicious cycle eventually renders the scenarios hard-to-believe: the audience sees, watches, but neither absorbs nor emotes, only consumes (and then expunges). Plausibility of such portrayed scenarios has become suspect. Studying neuroscience and its interconnections with memory might help understand the workings of the human brain—shining some light on this perplexing predicament we find ourselves in.

Guy Debord in The Society of the Spectacle writes, “The fetishism of the commodity-the domination of society by ‘imperceptible as well as perceptible things’ – attains its ultimate fulfillment in the spectacle, where the perceptible world is replaced by a selection of images which is projected above it, yet which at the same time succeeds in making itself regarded as the perceptible par excellence.”

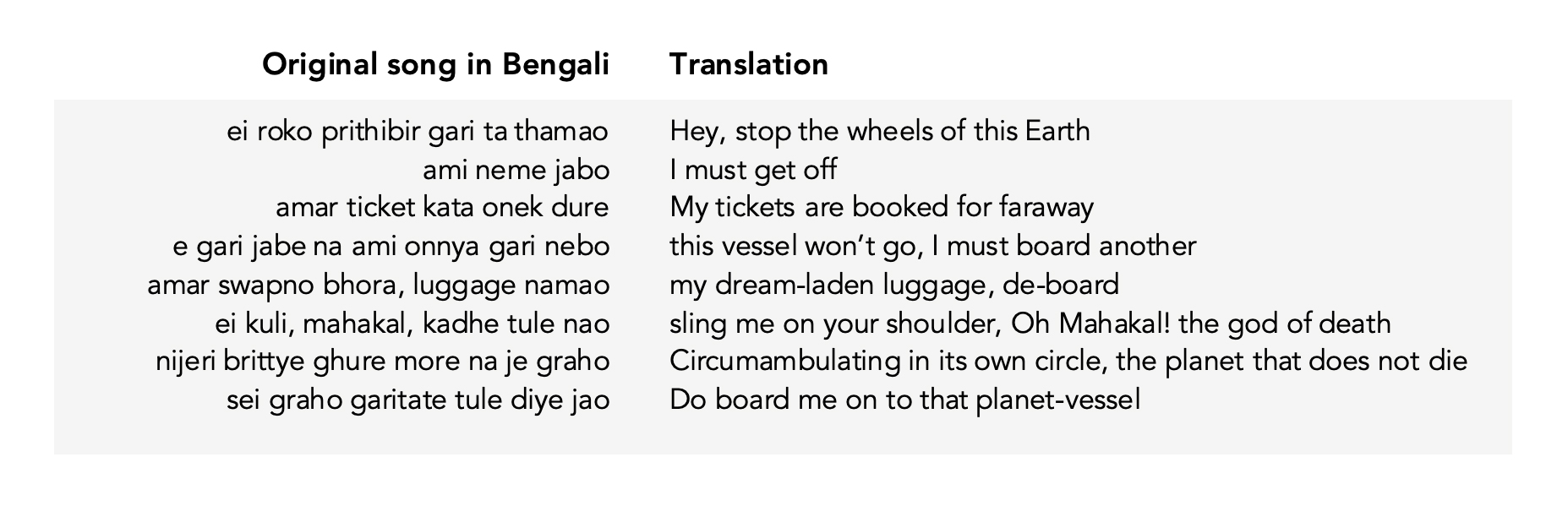

Max Pientner, though, had found a way around this problem in his drawing The Unending Attraction of Nature (1970/71).[14] Recently, in 2019, Klaus Littman created a public art installation titled For Forest (2019)[15] where he brought 300 trees into a stadium in Southern Austria. Both reminded us that once we have completely destroyed nature, we might have to visit trees in curated spaces like stadiums.

The Unending Attraction of Nature, Max Pientner, 1970/71

Olafur Eliasson in Ice Watch (2016)[16] laid out 12 glacial ice blocks from Greenland on a Parisian street emulating arms of a ticking clock. Uncanny juxtapositions – “forest & stadium,” “glacial ice & Parisian street” lead to a collision of “time-space,” “eternal-transient.” Were they weaving tales within Atwood’s speculative fiction or were these speculative documents?

Ice Watch, Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing, City Hall Square, Copenhagen, 2016

Source: YouTube / Studio Olafur Eliasson

Propelled by a fossil-fuel economy, the hyper capitalistic machinery of megacities, our myopic self-centrism and disregard for nature has made human extinction a fait accompli. Residents of New Delhi, co-suffer from heatwaves, air pollution and smog of hazardous proportions. The problem with air pollution is in its lack of visuality – it can’t usually be seen, only felt. This poses a unique challenge for artists – how to tell the story about something that can’t be seen, or of an impending doomsday?

How can we visualize issues like air pollution and global warming, something that not only unfolds over a prolonged duration, but also eludes visuality or easy categorizations from within the canon of photojournalism and documentary practice, or literature for that matter, without resorting to sensationalistic practices? Can our artistic responses bypass apathy, numbness and compassion fatigue to create sensorial experiences to aid in forging deeper understandings of climate-induced future and situate humans in the larger planetary (post-human) context? A way has to be found to arrest the continuous othering of the subject of climate change and environmental degradation. Driven by these concerns, I started working on An Elegy for Ecology* in 2016. [*An Elegy for Ecology is generously supported by PhotoSouthAsia, an initiative of MurthyNAYAK Foundation, KHOJ Studios under their Air Toxicities Grant 2020 (supported by Prince Claus Fund), and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan.]

The Great Derangement (after Ghosh), An Elegy for Ecology, 2019 © Sharbendu de

Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986) explaining his filmic philosophy in Sculpting In Time writes, “Through poetic connections feeling is heightened and the spectator is made more active. He becomes a participant in the process of discovering life, unsupported by readymade deductions from the plot or ineluctable pointers by the author.”

Family, An Elegy for Ecology, 2016 © Sharbendu de

Cartesian dualism arrogates all intelligence and agency to the humans with none to the nonhuman living beings (Ghosh, 2016) rendering the latter as – passive unintelligent liabilities – meant to serve the human race, thereby othering them. Following the enlightenment theory propagated in the 17th & 18th centuries, also known as the age of reason, we have projected man as exceptional, thus distinctly separate from the rest of the earth’s ecosystem, of which the human is just another cog in the wheel. A closer examination of the historiography must then be read as “human history,” written by the humans glorifying their exploits and exemplifying ourselves as exceptional. But would the tigers and deer, the octopus and phytoplankton, the forests and the mountains and the butterflies and moths, to name a few, concur with this history as the absolute history? If they could record the historical (and the present), what would those archives reveal? Well, we would conveniently fall back upon the age-old excuse that they cannot speak, have no soul and definitely lack conscience, and thus reduced to irrelevance, but has it ever occurred to us that maybe it is we who cannot hear? What if all these nonhuman living agents (including the planet) have maintained records of human-led assaults on the planet and its cohabitants?

The River Weeps No More, An Elegy for Ecology, 2017 © Sharbendu de

Lonely Man, An Elegy for Ecology, 2021 © Sharbendu de

Given our abrasive tendency for linguistic monoculture, has it ever entered our consciousness that perhaps it is our inability to comprehend those signals? That we are incomplete and inadequate? Why must every planetary species and system communicate to us using the human language system, which in itself is not singular? This problematic paternalistic viewpoint demands urgent contestations. The COVID-19 pandemic is a potent reminder of our ephemerality.

Post-humanities scholar Eduardo Kohn in How Forests Think[17] (University of California Press, 2013) states, “We have treated humans as exceptional – and thus fundamentally separate from the rest of the world.” He adds, “The first step toward understanding how forests think is to discard our received ideas about what it means to represent something. Contrary to our assumptions, representation is actually something more than conventional, linguistic and symbolic.” Referring to the presence of tigers being “everywhere and nowhere,” alluding to their elusiveness yet continuous presence in the Sunderbans, Ghosh, writes, “To look into the tiger’s eyes is to recognize a presence of which you are already aware; and in that moment of contact you realise that this presence possesses a similar awareness of you, even though it is not human. This mute exchange of gazes is the only communication that is possible between you and this presence – yet communication it undoubtedly is.” Kohn postulates, “How other kinds of beings see us matters. That other kinds of beings see us changes things.”[18] (Kohn, 2013; p. 1) He assists us with a bi-directional thought, “Understanding the relationship between distinctly human forms of representation and these other forms is key to finding a way to practice an anthropology that does not radically separate humans from nonhumans.”[19] (Kohn, 2013; p. 9)

Indigenous communities living closer to nature have always been aware of this circuitous relationship between the distinctly human, nonhuman living beings and other elements of nature. For example, the lesser-known Tibeto-Burman Lisu tribe from Changlang district living inside the forests of Namdapha in India’s remotest northeastern state Arunachal Pradesh (with whom I have engaged over seven years for the making of Imagined Homeland[20]), believe that “a parallel invisible world coexists in the same time-space continuum.” They call it Maamim and the invisible humans living there as Myiss. They say that for each Lisu, there is a similar looking Myiss in Maamim, and should one suffer or die, the same fate meets the other,[21] alluding to the “bush soul” concept. Invisible portals connect both worlds and stories of interactions with the Myiss exist in the Lisu world. Their relationship with the forest and its innumerable elements are influenced by similar belief systems, making them more respectful of nature and its cohabitants.

“The pain of roots and broken limbs, the fierce stubbornness of plants, no less powerful than that of animals and men. If these trees were suddenly to start walking, they would destroy everything in their path. But they choose to remain where they are: they do not have blood or nerves, only sap, and instead of rage or fear, a silent tenacity possesses them. Animals flee or attack; trees stay firmly planted where they are. Patience: the heroism of plants,” wrote Octavio Paz in The Monkey Grammarian (1974).[22]. The book was a result of his long stay in India as the Mexican Ambassador. Far from Mr. Paz’s influences, Andrei Tarkovsky through a Doctor’s character in The Mirror (1975) questions us, “Has it ever occurred to you that plants can feel, know, even comprehend? The trees, this hazelnut bush…they don’t run about. Like us who are rushing, fussing, uttering banalities. That’s because we don’t trust nature that is inside us. Always this suspiciousness, haste, and no time to stop and think.”[23]

Dealing with “the power of art,” Simon Schama writes, “…is the power of unsettling surprise.” He adds, “Even when it seems imitative, art doesn’t so much duplicate the familiarity of the seen world as replace it with a reality all of its own. Its mission, beyond the delivery of beauty is the disruption of the banal.” The future (as is the present) with chronic climate-induced environmental stressors on a rise is bound to cause significant psychoterratic distresses, thereby negatively affecting human health and well being. Can photography, then, bridge art and nature – infusing public imagination with newer and urgently needed insights about climate change, and thus our future? Well, that can only be answered by my fellow contemporaries. And I sincerely hope they do.

__________

[1] https://nacla.org/news/2019/12/27/un-violador-en-tu-camino-virality-feminist-protest

[2] The Climate of History, Dipesh Chakrabarty, University of Chicago, 2008 [Accessed 2016: https://pcc.hypotheses.org/files/2012/03/Chakrabarty_2009.pdf]

[3] The Climate of History in a Planetary Age, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Primus Books, 2021

[4] Climate Change and the Human Condition, Arvind Elangovan, Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. 56, Issue No. 31, 31.Jul.2021. [Accessed on 02 Sep’ 2021: https://epw.in/journal/2021/31/book-reviews/climate-change-and-human-condition.html.]

[5] IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, 2021 [https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/]

[6] The Impacts of Climate Change at 1.5°C and Beyond, Carbon Brief, 2018 [https://www.carbonbrief.org/scientists-compare-climate-change-impacts-at-1-5c-and-2c]

[7] Why Record-Breaking Overnight Temperatures Are So Concerning, Aatish Bhatia and Winston Choi-Schagrin, July 9, 2021, New York Times [Accessed on 15 July’ 2021 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/09/upshot/record-breaking-hot-weather-at-night-deaths.html ]

[8] The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh, The University of Chicago Press, 2016

[9] I liberally use the term ‘visual art’ to refer to the broad genres including documentary & feature films and photography.

[10] Atwood, M. (2004). The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake in Context. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, 119(3), 513-517. doi:10.1632/003081204X20578

[11] The Unreality of Memory, Elisa Gabbert, Atlantic Books, 2020

[12] AIDS and Its Metaphors, Susan Sontag, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989

[13] Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation),” The Massachusetts Review, 19:4, December 1978: 859-83.

[14] The Unending Attraction of Nature, Max Pientner, 1970/71 [https://forforest.net/en/news/max-peintner-and-the-unending-attraction-of-nature/]

[15] For Forest, Klaus Littman, 2019 [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ujH6aMHGxM&list=PLRAxPmaozmKFl8_BMIwoslksSXSVlEeV_&index=4]

[16] Ice Watch, Olafur Eliasson, 2018

[17] How Forests Think, Eduardo Kohn, University of California Press, 2013

[18] Ibid, (Kohn, 2013; pg. 1)

[19] Ibid, (Kohn, 2013; pg. 9)

[20] https://www.desharbendu.com/imagined-homeland

[21] Based on field work, unstructured interviews and personal interactions with members of the Lisu tribe over the seven years of working on Imagined Homeland (2013-19).

[22] The Monkey Grammarian, Octavio Paz, 1974, Arcade Publishing

[23] The Mirror, Andrey Tarkovsky, 1974

Copyright © 2022, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright © Imran Kokiloo

Copyright © Imran Kokiloo

Sharbendu De (b. 1978, India) is a lens-based artist, academic, and writer. In 2018, Feature Shoot recognized De as an Emerging Photographer of the Year. De received grants from the India Foundation for the Arts (2017), Lucie Foundation (2018), Prince Claus Fund & ASEF (2019), MurthyNayak Foundation (2021), and KHOJ (2021). He was shortlisted for the Lensculture Visual Storytelling Awards (2019) and Lucie Foundation’s Emerging Artist of the Year Scholarship (2018), among other nominations.

De's latest conceptual series, An Elegy for Ecology (2016-21) dealing with the subject of climate change, premiered at Phantasmopolis at the Asian Art Biennale, Taiwan (2021), and opened in India as his first solo show at SHRINE EMPIRE Gallery, December 2021. His former conceptual series, Imagined Homeland (2013-19) on the indigenous Lisu tribe from Arunachal Pradesh, has been exhibited widely.

De has exhibited across Asian Art Biennale (Taiwan, 2021), Vadehra Art Gallery (New Delhi, 2020-21), and SHRINE EMPIRE Gallery (New Delhi, 2020), PhEST (Italy, 2020), FORMAT (U.K., 2019), Serendipity Arts Festival (India, 2019), OBSCURA (Malaysia, 2019), MOPLA (Los Angeles, 2019), Voies Off Awards, Rencontres d'Arles Festival (Arles, 2018), Indian Photography Festival (India ,2018), Tblisi Photo Festival (Georgia, 2018), Goethe-Institut (Mumbai & Delhi, 2016 & 2017), Photo Kathmandu (2016), Econtros da Imagem (Portugal, 2016) and Diesel Art Gallery (Mumbai, 2012), among others. De teaches about photography and visual communications and writes on the subject alongside his art practice. He lives in New Delhi.

Find more about this photographer and his work.

Sharbendu’s Profile

20 November