In India, the history of professional illusion is multifold and lies at the intersection of religion, ritual, science, and performance. In the enlistment titled Chausath Kalas (or, Sixty-four Art Forms) in the Kama Sutra, magic is labeled as the twenty-first in the sequence. It is referred to here as “Indrajal vidya” – a system of knowledge that was used to contrive special effects on occasions (for instance, in ancient theater) that necessitated extraordinary happenings (such as apparitions and beheadings) without actually putting anybody at risk in the process; it was conceived purely as an art of deception, and has undergone various mutations since. The colonial magician-figure has its genesis in peripatetic communities (such as the madaris), who often performed to entertain potential patrons, of whom Mughal Emperor Jahangir was one. Jahangir recounts many instances of bewilderment in his autobiography, Tuzuk-e-Jahangiri, and bestowed rewards and titles on those whose skills pleased him. Of those at the receiving end, the Sarkars were one; they have continued the practice of magic through generations and are currently known by the “Sorcar” Gharana in Kolkata.

Photograph of jugglers and musicians at Madras, Tamil Nadu, taken in a studio

by Nicholas & Curths in c. 1870, from the Archaeological Survey of India Collections.

Courtesy: The British Library.

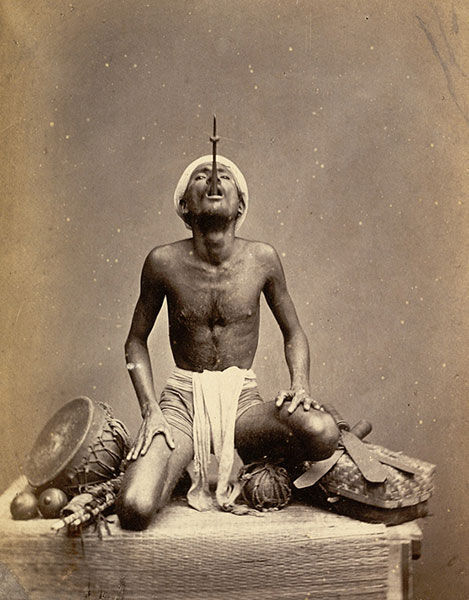

Studio portrait of a juggler performing the sword-swallowing trick at Madras, Tamil Nadu,

taken by Nicholas & Curths in c. 1870, from the Archaeological Survey of India Collections.

Courtesy: The British Library.

Going by the historical registers, the acts were performed before an eager public (that gathered progressively in voluntary strides) without monetary expectations; the excitement lay in the willful suspension of disbelief. Functioning in the imperial gaze, the street-performer, or jadoowallah’s tricks of trade provoked many white men to write books where they attempted to demystify their illusions with pejorative intent. Running alongside was also the scheme to appropriate the tricks without credit or compensation. In effect, many white illusionists stole the tricks, absorbed them into the Oriental mold, and marketed them to a western crowd that eagerly consumed palatable tropes of the East. The acts were advertised to the public through lithographs, and later, posters that foregrounded native figures as passive recipients of the tricks – this dispossessed them of any legitimate accreditation. With the advent of photography, both native and white magicians began to be recorded in continuation of the visual syntax that marked the former as anonymous mystics or masses and recognized the latter by name and prominence – in keeping with the imperial hierarchy and its attendant racism. Snake charmers, acrobats and jugglers were highlighted in the frame through the lens of the act, their instrument preceding their person. In contrast, the white magician’s personhood was foregrounded even when engaged in the act, their names prominent to this day in archival labels. The history of magic in the Indian subcontinent is replete with cultural conundrums and can be traced through evolutions in graphic design and photographic language. Captured in the studio, on the stage or the screen, the images reveal a cultivated culture of deception, its many virtuosos, and their entanglements in the matrix of power, vision, and exhibition.

Among the white appropriators, Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston acquired great prominence during their tenure. The former was touted an “escape artist” as he conflated magic with physical prowess through strongman stunts, while the latter mounted grand spectacles on stage. Houdini had even traveled to India with the express intent of hunting out illusions that had not been seen by the West, yet, and came across acts that later came to be titled by their exoticized appeal; for instance, the “Basket Trick,” the “Indian Mango Tree Trick,” and the “Great Indian Rope Trick.” The last in the series involved throwing a rope into the air which then became rigid, and a boy climbed up its length before disappearing into thin air. The trick generated widespread suspicion and fascination, and white enthusiasts spent much time documenting it for the purpose of exposition and practice. A paradigm shift occurred with this tendency, where India came to be perceived by the West as a mystical subcontinent – in a relatively improved departure from its racist classification as the “land of savages.” The plagiarism was evident though, as the use of native faces as subjects of and participants in the tricks in the advertisement posters became an inadvertent admission of their origins in India. Perhaps, the appeal lay in the reductive appropriation itself – a case bolstered by the fact that white illusionists commonly used the word “fakir” in their self-anointments (for instance, Houdini’s rise as the “Hindu fakir”[1]), which, in its etymological reference to the Sufi Muslim ascetic, does not hold ground.

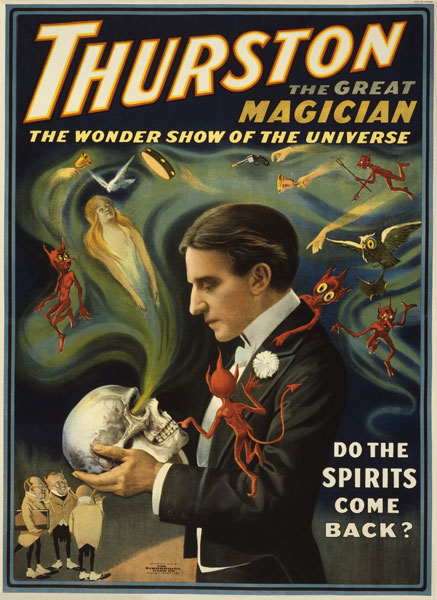

Posters such as this one from 1915 augmented Howard Thurston’s connection

to Spiritualism in the public eye.

Courtesy: The Rory Feldman Collection.

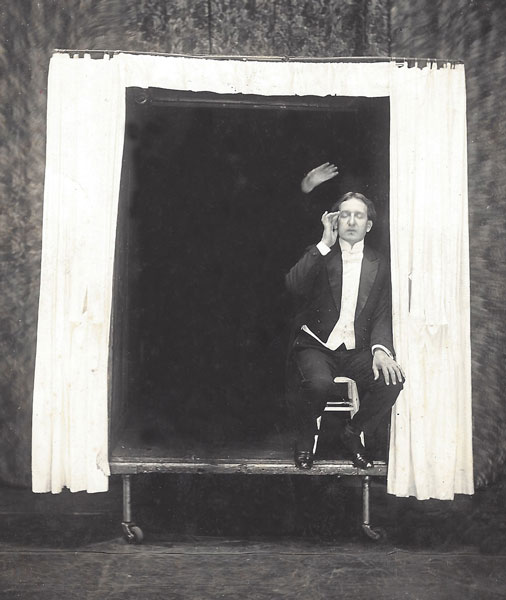

This production still, circa 1916, depicts a spectral hand reaching from the darkness

toward Thurston during a show.

Courtesy: The Rory Feldman Collection.

As spectacle became increasingly integrated with technology, the fascination with the unknown also led to a rise in mentalists that claimed to be able to make contact with the supernatural realm. This mainly stemmed from the western perception that the magician was a medium for the devil (as opposed to Indrajal vidya) – one that was used by Thurston to advertise his shows using the familiar image of the literary spirit, Mephistopheles[2]. In the South Asian context, Kuda Bux (an anglicized nomenclature), from Kashmir, was ordained “The Man with X-Ray Eyes.” He claimed to possess the psychic power of remote viewing, and publicly demonstrated his ability to describe words and visuals laid before him clearly, despite heavily bandaged eyes. Mind control, telepathy, and hypnotism slowly entered the visual parlance of stage magic, as illusionists actively capitalized on the audience’s fear of and desire for the paranormal. The Sorcar family vouched against propagating superstition, and used these tools for the stated intention of public entertainment – mainly as tangents to other tricks.

P.C. Sorcar Senior’s iteration of the Buzz-Saw illusion. Courtesy: P.C. Sorcar Junior.

It was not important to Western magicians that the spiritual and filial roots of magic in India be acknowledged in their nuances. The commercialization of magic, replete with grand props, support networks, exclusive audiences, and fierce competition divested magic (as it existed on Indian streets) from its spontaneous, collaborative exercise and generational persistence. It therefore makes for a compelling case of cultural reversal when Indian magicians began appropriating the tricks that western magicians were profiting from, and used them to mount self-exoticized renditions of the same illusions. The most prominent magician to have actively orchestrated such a reputation was P.C. Sorcar (Senior) from Kolkata, who is credited to have put Indian magic on the map. In 1956, on BBC television in London, Sorcar had decided to end his catalog of acts in the fifteen minutes of allotted time with the “Buzz-Saw” illusion[3] that involved passing a real, metal saw through the waist of a horizontally placed model and subsequently disproving any physical harm by reviving the person – all in full public view. When the saw had passed through the recipient’s body on BBC, the TV program abruptly cut to its news bulletin as time had run out – just as Sorcar was seen trying to revive an unresponsive model. The account goes that, as a seasoned magician, Sorcar was a master of timing, and that he had dilated his tricks such that the show strategically ended at such an anticipatory juncture. True to his purported intention, the BBC switchboard was saturated with calls overnight from viewers sure of having watched a live murder. A clarification had to be issued by the television channel, guaranteeing that the assistant was alive, healthy and would be touring with Sorcar on future shows; all major newspapers carried the headline the next morning.

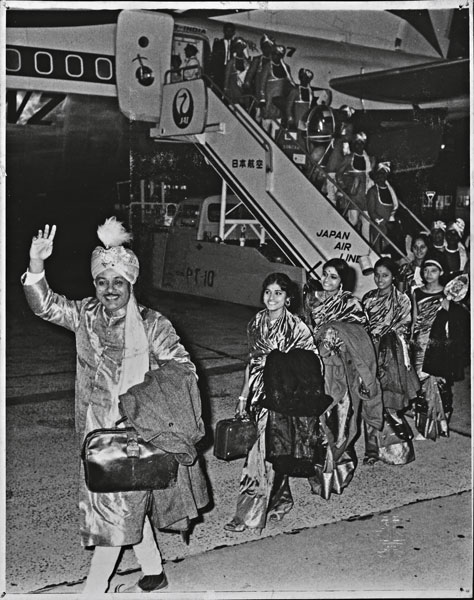

P.C. Sorcar (Sr) walking down a Japan Airlines aircraft in his Maharaja regalia

with female assistants and turbaned men behind him. Courtesy: P.C. Sorcar Junior.

Sorcar’s popularity rose to unprecedented heights post this landmark event, as English crowds thronged his following shows in London to catch the act in person. The television audience’s apprehension at the veracity of the sawing act, and conviction that Sorcar had engaged in miscalculation, also stemmed from Occidental prejudice against the native illusionist. In light of the unfolding events, Sorcar’s trick on live television can be read to have affirmed these epistemic suspicions before countering them to his advantage. His act was an assertion of presence to the British mass, a claim to visibility enabled by a deft use of the nascent medium of live television. TV offered a new territory of thrill, and Sorcar used it to imprint an image of a modern conjurer who had, until then, been largely ignored by the London press due to his race.

A publicity photograph depicting Howard Thurston with his female assistants,

and two native bodies who were part of his show as “Hindu fakirs”.

Courtesy: The Rory Feldman Collection.

Sorcar inadvertently set a precedent here, and many western magicians were soon seen in Indian costumes to attract audiences that had become attuned to its Oriental allure. Until then, they had been seen donning top hats and monochrome tailcoats, which registered in production stills as an effort to assimilate with the English gentry. Conversely, this costume also became a tool of imperial emulation for many male Indian magicians at the time – in tandem with a deep-seated colonial yearning. The costume also lent a sartorial consistency to the profession. Dressed in the readily identifiable coats, native magicians often entitled themselves “professors” while performing amongst a white audience in Calcutta[4], in an attempt to ascribe their occupation a degree of social prestige[5]. Sorcar – a nationalist who did not want to mimic the British ensemble – adopted the distinctive lexicon of the sherwani and turban; their genesis lies in being offered as gifts by Raja Hanvant Singh of Rajasthan as tokens of appreciation. The royal figure had also simultaneously ordained him the superlative “Maharaja of Magic”[6] – a title that gained international traction with Sorcar’s rising popularity. Based on a primarily male fraternity culture, women are almost absent from records of professional magic, except as assistants or appendage to male magicians. As Othered bodies, women have visually registered in the acts as receptacles of male displays of power – albeit with notable exceptions, such as Adelaide Herrmann and Maneka Sorcar, the latter a ninth-generation practitioner in her family. The absence of women in mainstream magic may have stemmed from anxieties around a potential gender reversal of power dynamics (especially in light of the ongoing Suffragette movement in London in the 1950s[7]), in addition to the discomforting historical association of female sorcery (and agency) with witchcraft.

Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1952), directed by Homi Wadia. A composite picture, the poster

depicts a genie (supernatural being possessing magical powers) holding Aladdin’s palace precariously

against the edge of a waterfall. Displays of physical prowess between male bodies through fighting

was as integral to these “jadoo” films as the use of special effects. Lobby card.

Courtesy: Priya Paul Collection @ Tasveer Ghar.

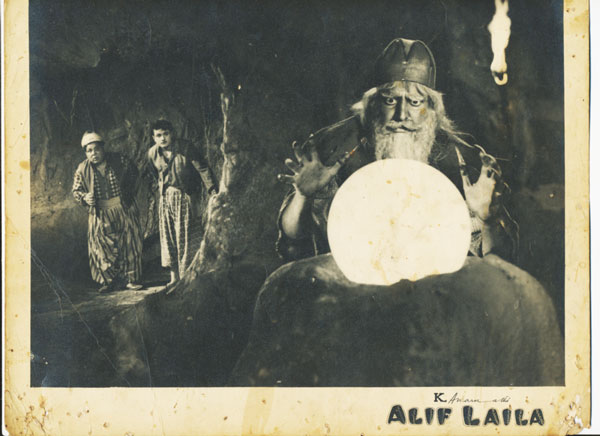

Alif Laila (1953), directed by K. Amarnath. Caves, crystal balls and sorcerers were used as

visual leitmotifs along with inter-personal intrigue as a narrative anchor

in these fantasy films. Lobby card.

Courtesy: Priya Paul Collection @ Tasveer Ghar.

Stage magic provoked a politics of corporeal pleasure similar to that experienced in the cinema. The prospect of watching an illusion unfold in real time on television initially augmented the need to be present in person at the corresponding show. But with the subsequent advent of cinema and experiments with cinematic techniques, special effects gradually became a substitute to the same end. Consequently, fantasy shows and films drew from the photographic and televised histories of magic to cumulatively create a lowbrow realm of motion pictures. The genre of the fantastic offered possibilities for spectacle, stunts, and magic, which the films used to create hybrid landscapes – in response to global Oriental obsessions at the high point of cosmopolitan modernity[8] . Anchored in a loosely Islamicate culture that held transcultural appeal in their referential ambiguity, television shows and films such as Alif Laila (two series of stories from the Arabian Nights, 1993-97) and Hatimtai (1990) crystallized their visual syntax in public memory. The mythological film, Kaliya Mardan (1919), also borrows from Hindu divine iconographies in its use of special effects. Here, the religious image is mobilized through trick photography, in addition to the existing apparatus of projections, traps, and mobile sets integral to live performances. Studios such as the Wadia Movietone and Basant Pictures looked to engage audiences at a visceral level that was achieved with the use of special effects – as animal transfigurations, teleportation, flying carpets and divine mercy were actualized through a formal aesthetic that primarily drew from the tableaux conventions of pre-existing oral and literary traditions. The general familiarity of the stories from narrative retellings further heightened the pleasure of the special effects as they made legible an extant culture of attractions[9] through spectacular excess. Echoing the cross-fertilizations that occurred with the advent of magicians like Sorcar, a quasi-Orient thus materialized on screen, which was marked by as well as different from imaginations of the European Orient[10], as plural temporalities collapsed into an opulent elsewhere. The assembly of bodies is also effectively restructured, as audiences now occupied dispersed geographies, and the “liveness” of stage magic translated to an altered arrangement of cinematic exhibition.

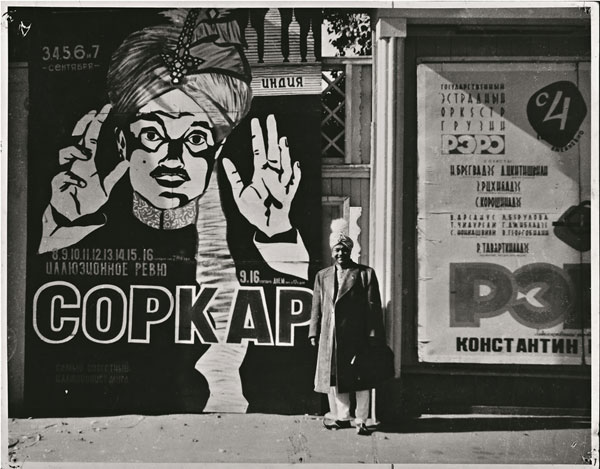

P.C. Sorcar (Sr) posing in front of his own poster for a show in Russia. Courtesy: P.C. Sorcar Junior.

Magic in the Indian subcontinent has been a fertile site of appropriations and borrowings. While the western gaze subjected magic’s varied histories to an essentialist Othering, Indian magicians like Sorcar (who belonged from a lineage of practitioners) and his contemporary, Gogia Pasha (who appropriated an Egyptian persona on stage) also keyed into the Othering gaze to reclaim magic as profession on a transcultural stage, thus nullifying a long history of unidirectional theft. Pasha also recognized the potential of the cinematic medium in terms of outreach, and appeared as a showman in mainstream films like Ek Thi Ladki (1949) and Dilruba (1950). Attesting to their increasing recognition, the photographic syntax of Sorcar and Pasha’s posters foregrounded the iconicity of the illusionist himself, the suspense of his act now embedded in the image without visual explication. One can trace through these records evolving models of masculinity of the magician-figure through the decades, as the (male) body performed its proficiency through a public exercise in control. With the native magician embodying that control on the professional stage, masculinity became accommodating of the agency of the colonized body, dismantling thus the white supremacist claim over the practice of illusion as entertainment. In the contemporary moment, magic has become marginal art from a lack of institutional support, with a few bodies attempting to rehabilitate traditional magicians to their craft, such as the ‘Illusion and Reality Magic Research Society’ – an initiative of the Sorcar family in Kolkata. Despite a history of exploitation, penury, and erasures, archival records of magic capture not only the pulsating popularity of conjurers through the ages, but also its genesis in (and sustenance by) the escapist fantasies of a geo-politically expansive audience.

__________

[1] Zubrzycki, John. “Introduction: ‘So Wonderfully Strange’”, Jadoowallahs, Jugglers and Jinns: A Magical History of India. Picador India. 2018. Unpaginated.

[2] Sorcar, Maneka. In conversation over Zoom. September 7, 2021.

[3] A version of the division illusion developed in the 1920s by American magician Horace Goldin.

[4] The official and British-endowed name of Kolkata city until 2001.

[5] Sorcar, Maneka. In conversation over Zoom. September 7, 2021.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Oatman-Stanford, Hunter. “The Magician who Astounded the Worldby Conjuring Spirits and Talking with Mummies”. Collectors Weekly. May 5, 2015.

[8] Thomas, Rosie. “Bombay before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies”. Bombay before Bollywood. Orient Blackswan Private Limited – New Delhi. 2014. P.9

[9] This notion comes from the “cinema of attractions”, a theory proposed by Tom Gunning in his essay, “The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde” to suggest that narrative is preceded by the act of looking and the excitement of the image.

[10] Thomas, Rosie. “Thieves of the Orient”. Bombay before Bollywood. Orient Blackswan Private Limited – New Delhi. 2014. P.33.

Copyright © 2022, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Researcher, writer, and performer, Najrin was awarded the first Art Writers’ Award (2018-19) by TAKE on art magazine and Swiss-Arts Council Pro Helvetia. She has since been associated with various platforms as a writer, including ASAP|art, an editorially driven archive on lens-based cultures in South Asia. Najrin’s research interest is situated at the intersection of moving image histories, archival politics, and institutional omissions. Exploring the potential of the image to confuse, deflect, and reveal, her writing gravitates in the direction of digital, forensic, and fictive vocabularies. She completed her M.A. in Arts and Aesthetics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Copyright © Najrin Islam

Copyright © Najrin Islam

20 November