A class photo, near Chamundeswari Devi Temple.

(Mysore/Karnataka) 2018 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Suresh and Amit watched the elders’ card game.

(Malerkotla/Punjab) 2017 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

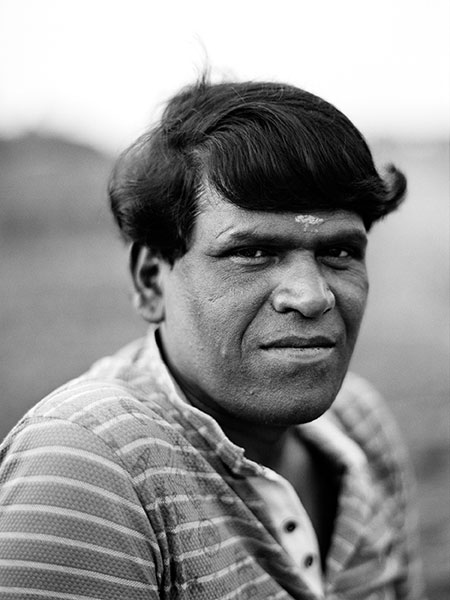

We sat in the fields near the Krishna River. Imtiyaj and Ravsaheb

spoke of their sexualities, family bonds and the futures they envision.

(Sangli/Maharashtra) 2018 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

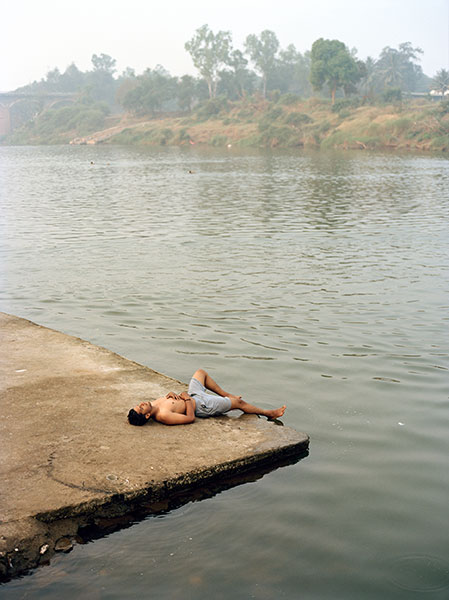

I like walking along the Krishna River early in the morning.

(Sangli/Maharashtra) 2020 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Suresh and I sat in the cruising area of Cubbon Park, near the Parade Grounds.

(Bangalore/Karnataka) 2019 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

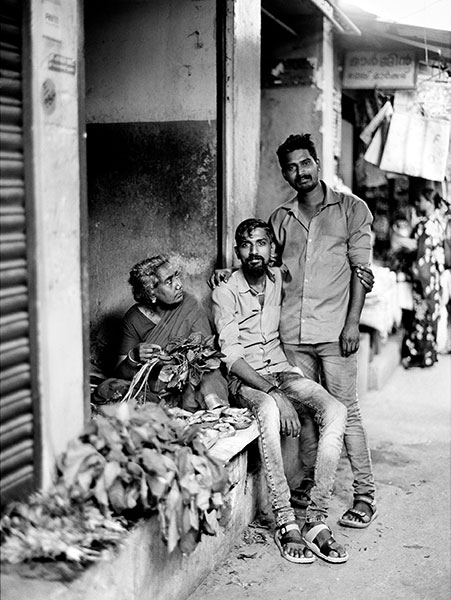

Rajeev and Arun, with Amma looking on.

(Trivandrum/Kerala) 2019 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

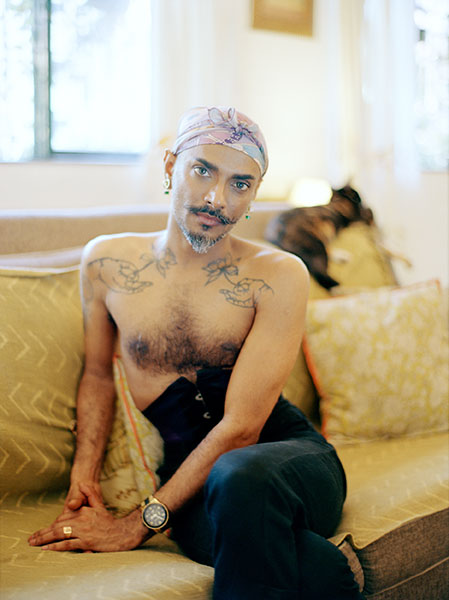

Elton recounted how his penchant for dressing up and applying make-up as a boy

used to entertain his family, until the moment when he eventually came out to them.

(Mumbai/Maharashtra) 2022 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

After dark, Ravsaheb meets his friends at the central bus stand.

There they socialize while waiting for johns.

(Sangli/Maharashtra) 2018 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

A cinema hall in Mumbai where men come to cruise for ‘fun’ with other men.

I had a long conversation with a man who asked me to name him “Amit.”

(Mumbai/Maharashtra) 2018 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Akthar was eager for us to meet his best friend Dilshaad, in his barber shop.

His son Arsh arrived to call Akhtar home for dinner.

(Malerkotla/Punjab) 2017 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

A morning walk near the sea wall.

(Mumbai/Maharashtra) 2018 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

I woke up at sunrise and encountered daily-wage earners

who were loading gravel onto a train near the Ganges.

(Sahebganj/Jharkhand) 2017 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

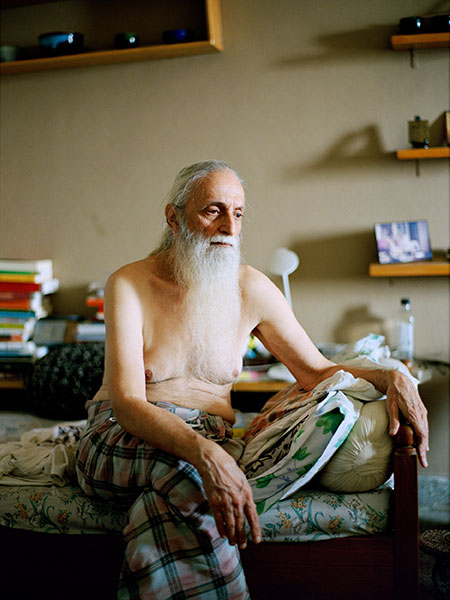

Owing to a Colonial Era law that criminalized homosexuality,

Hoshang has never dared to live with a boyfriend, fearing

any landlord would throw him out of his home.

(Hyderabad/Telangana) 2020 – Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Copyright © 2022, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Since the invention of photography, there have been a great many artists from around the world who have been inspired to photograph on sojourns to South Asia. Some have visited once, others often or for long periods to work on their projects. These artists and their work in the region will be found on PhotoSouthAsia under Features.

Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Photograph © Marc Ohrem-Leclef

Marc Ohrem-Leclef (German, based in Brooklyn) is a lens-based artist who explores themes of identity and belonging, in particular where their mainstream representations perpetuate veiled inequalities. His collaborative practice manifests in long-term projects, employing documentary and performative modes. His artwork is held in the collections of Museo de Arte do Rio (Brazil) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art Library (N.Y.), and has been exhibited internationally. Select reviews include Artforum, British Journal of Photography, The Atlantic, Der Spiegel, and Slate. A MacDowell fellow, he has received numerous awards and teaches at ICP, among other institutions.

Ohrem-Leclef is a Breda Photo Artist.

Artist Website: Marc Ohrem-Leclef.

When visiting India first in 2009, I found beautiful liberty in how men express their care and love for one another through gestures of affection in the public space. This male intimacy can be described as ‘traditional’ and does not only exist in India. Being able to freely express through touch that one is close to another - without being judged or categorized - is not something that I knew from my life in the Western hemisphere. It strikes me as deeply human and beautiful.

As far apart as the Earth is from the Sky (Original title Zameen Aasmaan Ka Farq, as recorded in an interview with a collaborator) is a photographic meditation on touch as an expression of love, based on my research on the culture - and politics - of touch between men in India.

I am interested in how Indian men today navigate shifting norms of the kinds of intimacies deemed acceptable (for example, think of the influences of Patriarchy, Colonial Masculinities, the influx of Western Gender Identity Politics, as well as the current divisive political climate). As a queer-identifying man, the experiences of those men who seek intimacy and love with other men - beyond what is considered acceptable and generally visible - in this context move me in particular.

All projects I work on represent a learning opportunity for me: My journey of the process of acquiring knowledge and in sharing that knowledge, be it hard ‘facts’ or almost intangible sentiments, are at the base of my interest in the lens-based works that I make in my collaborations. When I began my research on Zameen in 2016 I started out with fairly narrow concepts around how to address the themes of gender, masculinity, and intimacy through my photographs.

I soon realized that I had to let go of these concepts and allow the work to take me to unexpected places, both emotional and geographical. One expression of this development is that I give the texts - they are entirely sourced from recorded conversations with my collaborators - equal space and importance in the work. In dialog, the two media enrich and complicate one another, creating subtler representations. Still, attempting to phrase the deeply private and intangible subjects I address in Zameen in images and words is incredibly difficult. It requires a slow and organic process that I have learned to embrace during my work in India. The change of the project’s title from Jugaad - Of Intimacy and Love to the more open-ended Zameen Aasmaan Ka Farq about two years ago represents another shift in how I understand the central elements of work, and how I hope audiences will read and connect with it.

I strive to get beyond the surface in my work. The problem with photography is its inherent risk that all it records is surface - how surfaces handle light. Kindness is my way of creating a bond with those I make photographs with, which in turn can create an opening in the surface. I bring honesty, love, and affection to any encounter and to the conversations I have with my collaborators. Most people respond in kind, allowing me to glimpse beyond their surface.

The question regarding cultural barriers and being able to connect with collaborators are - maybe surprisingly - very separate, in my experience. As much as I spend time educating myself on everything from ancient histories to current Indian pop culture, some cultural divides persist. Language barriers can deepen this divide, which is why I always travel with an assistant who speaks the local languages of a region where we travel. However, differences in our cultures do not necessarily have an impact on how I am able to connect with collaborators and build trusting relationships - in fact, one of the surprising dynamics in doing this work has been that many collaborators feel more comfortable in speaking with me about very private experiences only because I am not a part of their social circle. This dynamic is central to motivating me to expand the work to recording over 120 conversations in 12 languages, in places spanning from urban centers to tribal hamlets in remote areas.

Zameen Aasmaan Ka Farq originated in my experiencing a certain freedom in the expressions of male love and intimacy in India. My desire in learning about this culture quickly expanded to grappling with the experience of queer identifying men in India who navigate a period of heightened awareness around the politics of touch, with a society marked by important advances in the plight for equality for LGBTQ+ communities (I began the work before the decriminalization of homosexuality in 2018) and continued stigmatization of homosexuality.

While I connect with my collaborators on many levels irrespective of their identities, I never compare myself to them. I am interested in speaking ‘person to person,’ opposed to ‘interviewer to respondent.’ I do reflect back on my personal journey and identify common experiences, which I openly share in my conversations. But I make this work to amplify my collaborators’ voices because I believe we stand to learn from them, not to draw comparisons or point out differences. I believe that focusing on shared human experiences is more successful in motivating audiences to engage with the work, to engage in critical thought, and provoke questions about our existing notions.

I purposefully include voices belonging to a broad range of identities, castes, classes, religions, and geographies in my work in Zameen, including activists and those trained in sociology. In their sum, all of these voices create nuanced representations of the identities I encounter. During that process, the close collaboration with my assistant and translator is of utmost importance. Their ability to not only translate my words but rather my ideas into notions that are relatable to my collaborators is key in allowing me to touch on subjects that many people I have worked with may have never (had to) put into words. Because India is home to 22 official and well over 100 spoken languages, I regularly have to find new assistants who speak the languages of places I plan to visit. The way my collaborators express themselves in physical terms and through their spoken words changes with each region - it is one reason why I have covered many thousand kilometers on my journey for this work.

The work captures the amalgam of how my collaborators experience the shifting norms of acceptable intimacies between men and an increasing lack of acceptance of traditional fluidity of gender and sexuality. It attempts to offer an understanding of both the beauty and difficulty that intimacies exchanged in unspoken, hidden spaces can represent, and what the fight for equality of LGBTQ+ communities - which inevitably draws clear lines of gender identities and sexualities - means for those spaces that are more accommodating to fluid identities.

Looking forward, it asks what “equality” - that itself is rooted in a set of definitions - has to offer to those who do or wish to live openly outside the heteronormative structures today. Here, Zameen does not offer answers or solutions - it merely raises questions around the evolving politics of touch between men and asks us to reflect on what stands to be gained, and lost.

20 November