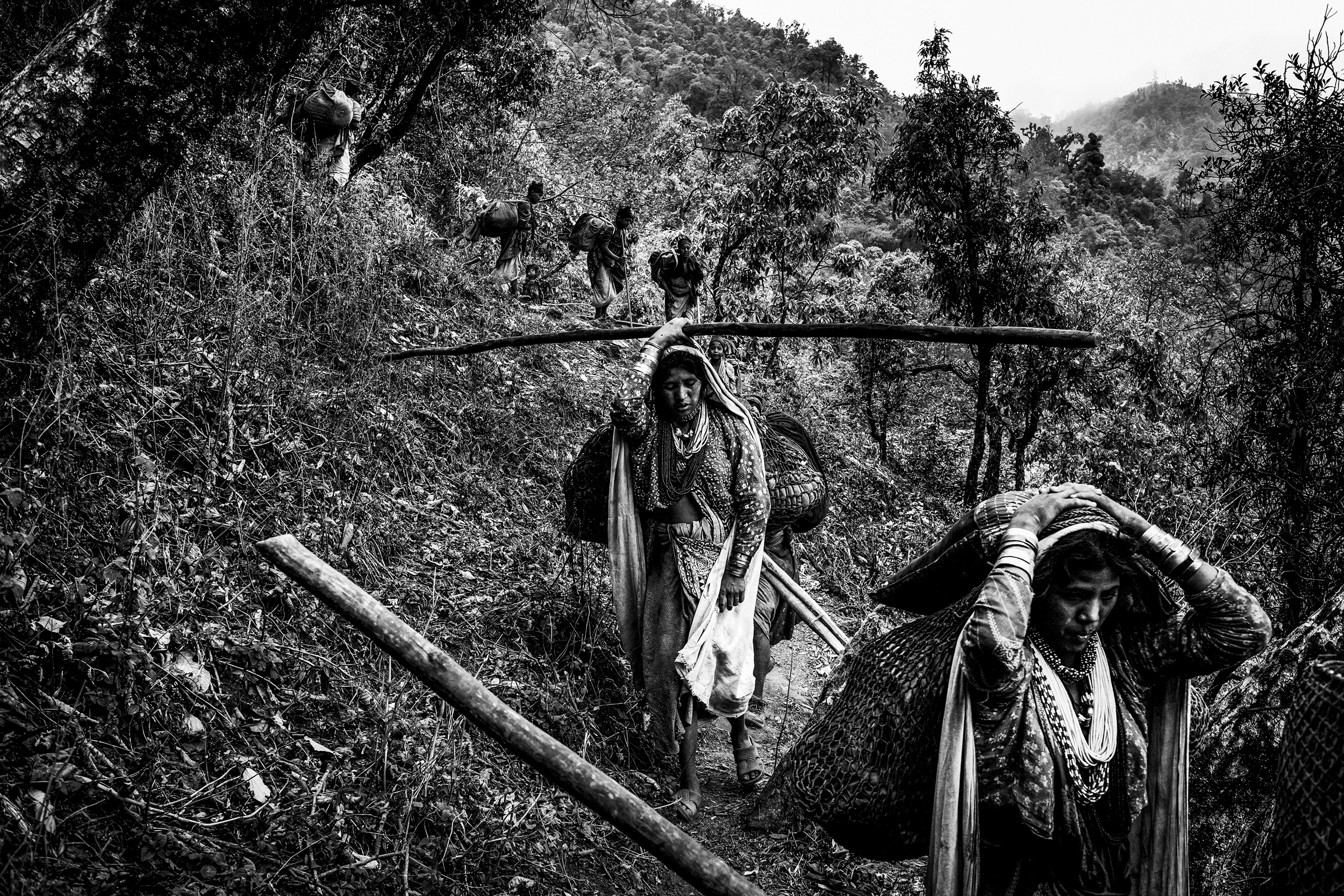

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

Photograph © Kishor Sharma

"The duniya (the outside world) farms and makes their homes. We enjoy living in the forest," says Maeen Bahadur Shahi, former mukhiya (headman) of the last Nepali hunter-gatherers, the nomadic Raute tribe.

"It is possible that hunter-gatherer populations currently residing in central Nepal, such as the Kusundas, Chepangs, Rautes, and Rajis, may be the descendants of the Patu people that developed the first culture of Nepal some 7000 years ago," Aashish Jha, a post-doctoral fellow at Standford University, writes. "Understanding the origins and demographic histories of present tribes of Nepal may reveal novel aspects of ancient human dynamics in Asia," he adds.

However, the Raute way of life is increasingly under threat. After the concept of community forestry was introduced in the '70s in Nepal, tensions arose between the Rautes and the communities that were stewards of the forests. Used to having free reign of the woods, the Rautes were not allowed to freely cut down trees anymore. To make matters worse, the government started to give cash handouts to the Rautes, which led to their interacting more often with other communities. They now get drunk with the locals, sometimes even getting into fights. There have been several attempts by government and non-governmental organizations to settle down the Rautes, which they so far have declined.

"Around the world, there have been tragic outcomes of forcibly settling hunter-gatherers… The Rautes too are not likely to successfully adapt to a farming lifestyle," social scientist Jana Fortier argues. It has also become harder to find space for nomadic traditions. If anyone dies in the community, the Rautes immediately leave the place, burying the dead with their personal belongings. They also don't drink flowing water and standing water that is easily accessible and can be difficult to find.

For elders like Maeen Shahi of the last nomads of Nepal, these experiences are difficult, but he accepts them as something eventual with the changing of times. "This has been the way for long. It will continue for as long we can," he says.

20 November