Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

Photograph © Sheba Chhachhi

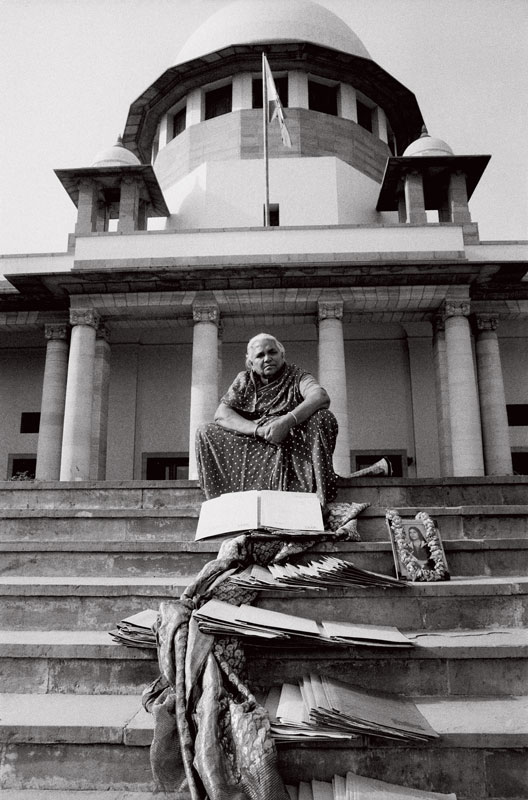

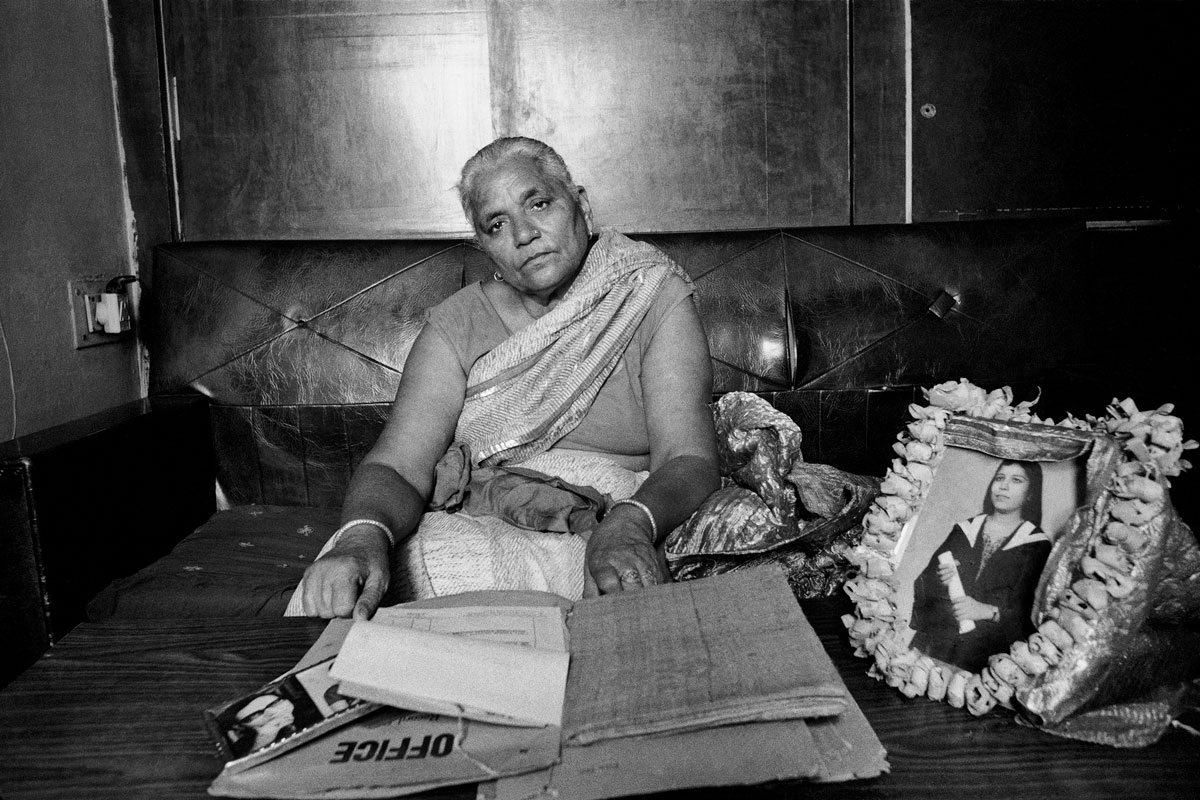

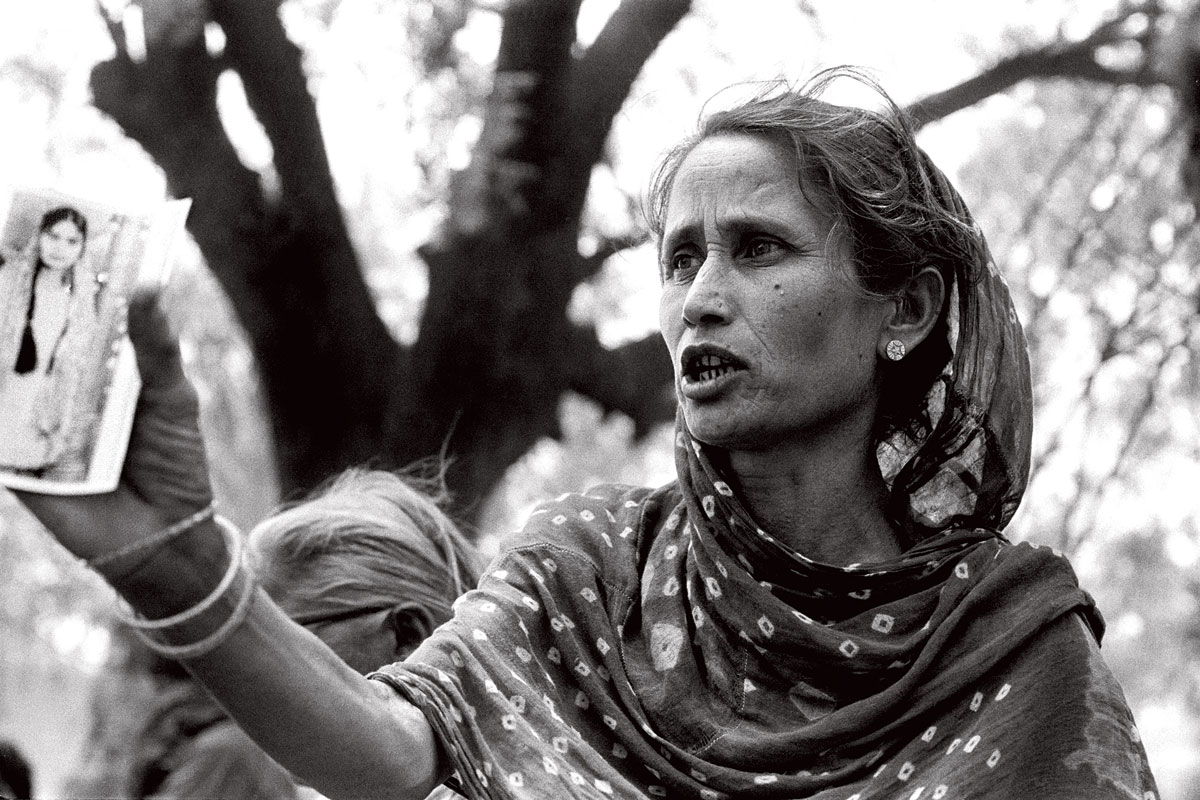

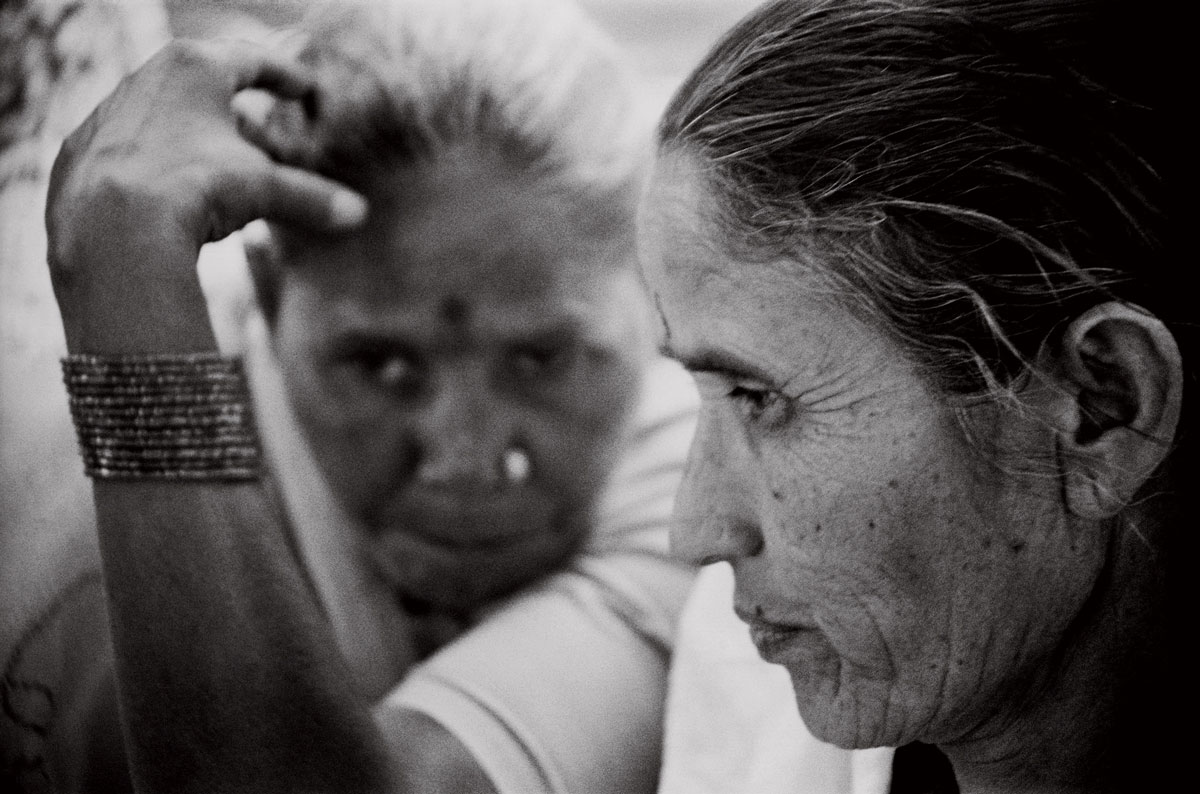

Seven Lives and a Dream

1990–91 | 18 silver gelatin prints, selenium-toned: 11 prints,

76.2 x 50.8 cm each; 7 prints, 55.88 x 38.10 cm each

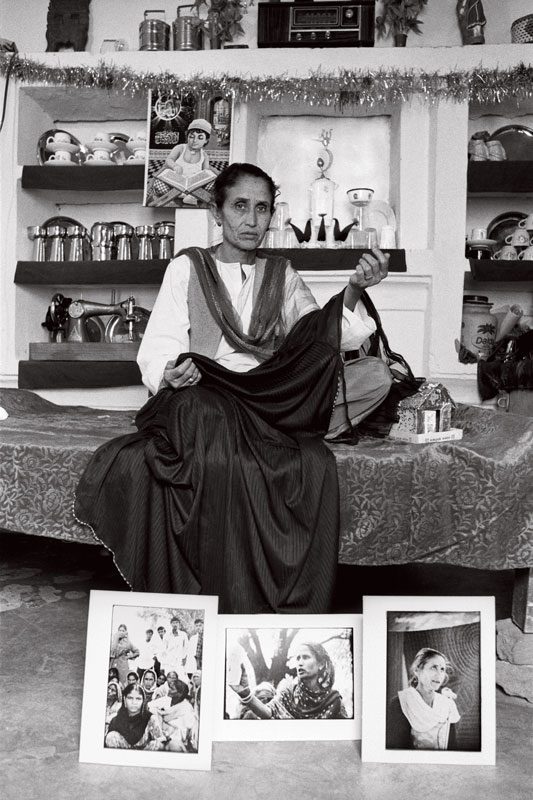

Assumptions about the indexical nature of the photograph continue to pervade the quotidian visual realm. Examining the truth claim of photography opens up vexed questions around objectivity, representation and the nature of the real. Interested in making the subjective and constructed nature of photography explicit and working with the photograph as fiction rather than as document, I moved from documentary practice to developing staged collaborative portraits.

I invite seven women – friends, sisters, and fellow activists – to collaborate with me in developing a series of staged portraits. Each woman chooses a place, a posture, materials, and objects that she feels can speak of her, tell her story. Apa brings a small hut, meticulously made from a shoebox, glue, and tinsel paper: ‘My story is a shanty town story.’ Shanti borrows an axe, spreads wheat on the floor and opens her diary. Sharada offers a bus-pass, a tiffin-box, a set of glass marbles and, unexpectedly, a seat in a DTC bus as the place where she is most with herself. The mise-en-scène is located at diverse sites in Delhi: Satyarani chooses the steps of the Supreme Court of India, Devi her single-room home in a resettlement colony. Urvashi wants to set up her collection of writing machines on the street, but we have to compromise and use a spare room.

The process of developing these ‘theatres of the self’ is complex and long-drawn-out, taking shape through intense, intimate interaction over several months with many revisions and retakes. Both subject and photographer are altered, the conversation of independent individuals made possible by a mutual becoming. We create an intersubjective field: a space of shared subjectivities that is neither hers nor mine but comes into being between us, mutually constitutive and unique to that moment and that process.

A quasi-fictional representational method emerges, which draws on vernacular practices of the bazaar studio, yet is significantly different. Multiple selves appear: each woman includes a previous photograph within the set-up, refusing to be contained within the essentializing unique portrait. We are making fictional truths, performing the real.

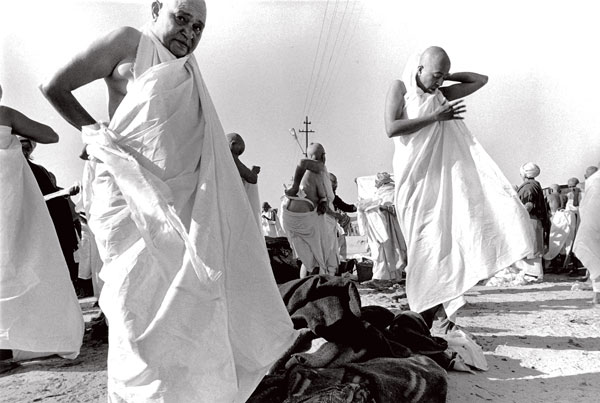

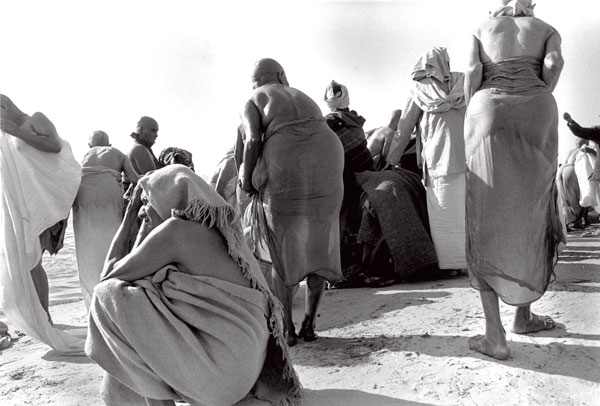

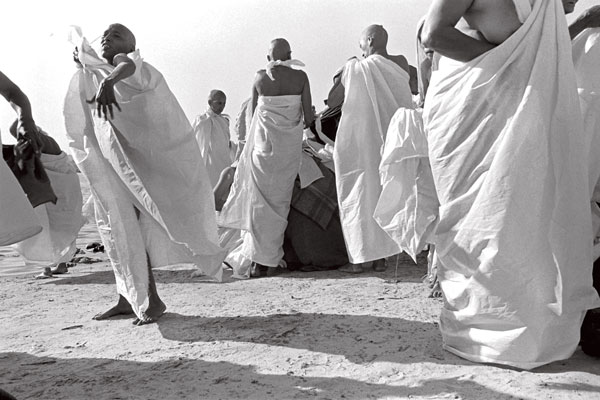

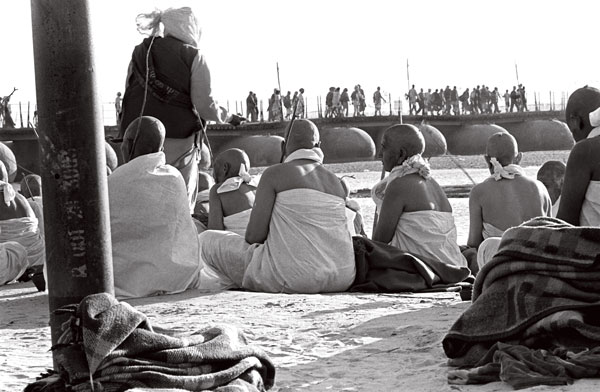

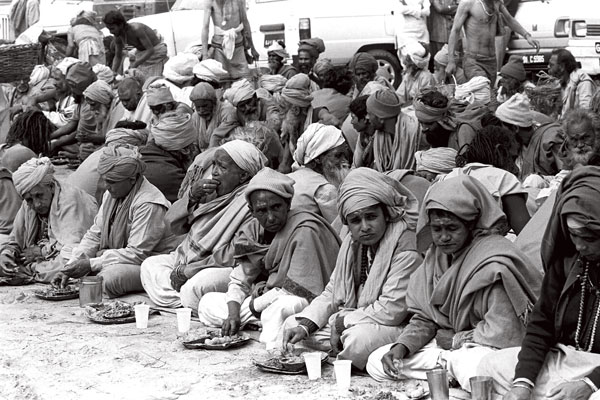

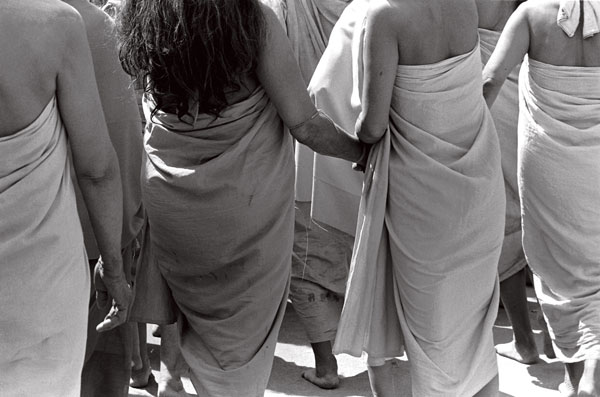

Initiation Chronicle

1998–2001 | 22 silver gelatin prints | 76.2 x 50.8 cm each

The woman initiate is stripped of her secular and gendered identity. Naked, shorn, fasting and sleepless, she prepares all night to be divested, by dawn, of name, family lineage, caste, place of origin and ancestors up to seven previous generations. On the banks of the river, she performs her own death rites. The photographs, taken while I was an honorary insider, follow a group of women as they perform this sloughing-off of old identities, step by step, over three days, until their immersion in the river. Each woman arises from that baptism reborn as an ascetic, renamed as a daughter of the river.

20 November