Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

Photograph © Vasantha Yogananthan

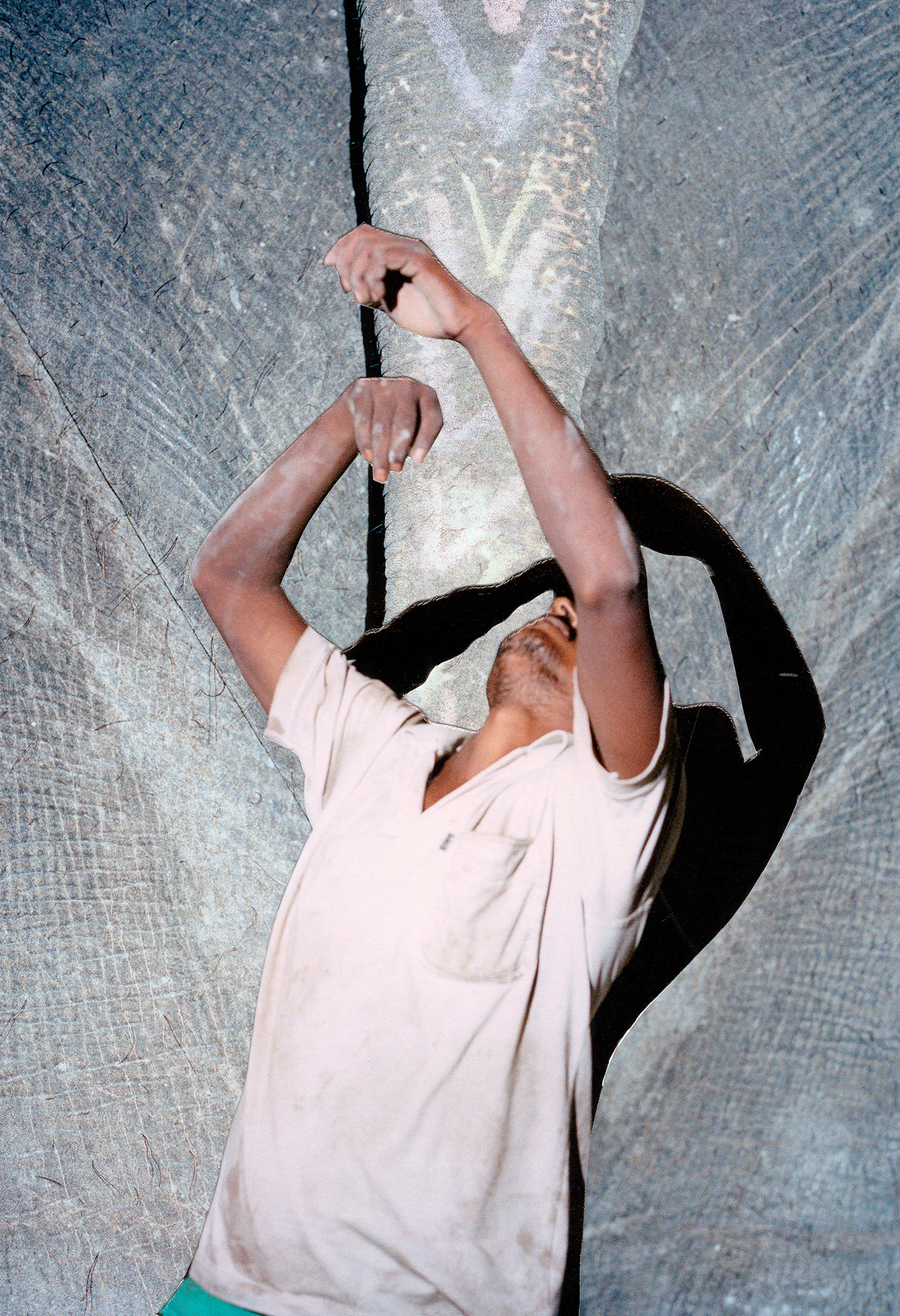

Afterlife is the sixth chapter of Vasantha Yogananthan’s 7-book project, A Myth of Two Souls (2013-2021), inspired by the epic tale, the Ramayana. A classic epic at first sight - a love story, an abduction, a war - the Ramayana has been continuously rewritten and reinterpreted and continues to evolve today. Drawing inspiration from the imagery associated with this myth and its pervasiveness in everyday Indian life, Yogananthan’s series is informed by the notion of a journey in time and space and offers a modern retelling of the tale.

Afterlife is centered around the bloody war between Rama and Ravana, the demon king of Sri Lanka. After being separated from his wife Sita for many years during her capture by Ravana, Rama is unsure of her fidelity and voices his suspicion. Hurt by these allegations of disloyalty when she had been steadfastly devoted to Rama, Sita willingly undergoes a trial by fire to prove that she is chaste. The fire god Agni himself appears in person from the burning pyre, carrying Sita in his arms, protecting her from his fiery wrath, and restores her to Rama, testifying to her 'purity.'

In many cultures of the ancient world in Asia and Europe, it was believed that the innocence of the accused could be demonstrated if they survived an extreme ordeal such as burning. In India, fire is a symbol used in Hindu ceremonies that form a rite of passage: births, marriages, and funerals. The reason for this is because, of the four elements (earth, water, air), fire is the only one that cannot be polluted. The trial by fire is perhaps the most controversial part of the Ramayana and, although the epic was written around 300BC, this patriarchal perspective stands the test of time. It hasn’t been more than twenty years since Indian women writers reversed the narrative to question the Ramayana’s influence on the collective unconscious.

These writers have also been questioning the violent events that are part of the Ramayana. Most of us will never go to war and yet we all have a collective experience of it, mostly through news photography and movies. Most of us are horrified by what war can be and yet we cannot help but watch violent content and imagery. Why do we all feel this uncomfortable attraction towards darkness? If the pictures composing Afterlife were shot in Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu over two editions of Dussehra - the Indian festival celebrating the end of the Ramayana and the victory of good over evil - they don’t document the festivities nor any real-life battles. They seek to be a visual response to what war can be - not on a physical level, but rather in one’s mind. Although we rarely see Sita, the series is told from her perspective. She is taking us on the battlefield, unafraid of the soldiers and the many creatures roaming in the dark night.

There is an otherworldly gravity at play in Afterlife, as Yogananthan combines analog photographs with digitally-erased background and collages made of cutout prints. The series embraces the possibilities offered by both analog and digital photography. Alongside the crucial act of composing and taking a photograph, Yogananthan conducts studio-based work to intervene and interpret images and introduce new narratives by playing with material forms.

20 November