Priyadarshini Ravichandran / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Priyadarshini Ravichandran / Photo © Sohrab Hura

My mother often recounts her engagement days with my father, during which they would exchange long letters – sometimes with banal details, and at other times quiet remembrances. Sitting in a bungalow in Hyderabad, she would talk about the falling allamanda flowers in the backyard of her home, as my father read the words while staring out at the Arabian from his Nani’s home at Chowpatty, Bombay. The anecdotes were my first introduction to the act of letter-writing, which at the time felt rather tedious in a world where phone calls on the move were increasingly accessible. Now my mother’s cursive handwriting against my father’s large and elaborate scrawls seem like precious time capsules, holding within them perceptible memories.

But why would I begin a story about a photography exhibition with narratives about my parents’ romantic memoirs? The answers lie in the multiple galleries of Sunaparanta, Goa Centre for the Arts that is currently showcasing the works of introspective storytellers under a show titled Growing Like A Tree: Sent A Letter. Initially curated by artist Sohrab Hura, at Ishara Art Foundation in Dubai in 2021, the show is currently in its third iteration and witnesses the curatorial debut by artists Bunu Dhungana and Sadia Marium Rupa.

Walking through the space almost feels rhythmic, and eminently sensorial. Letters, both literal and figurative, prance about the walls making me revisit the love notes from my parents, present-day emotions, and forgotten evocations amidst works reflecting the personal as well as political histories of South Asian imagemakers. Much like letters that demand time and a sense of contemplation, the exhibition invites you to read – between the lines and alongside them. The white walls are mirrors, devoid of artists’ names or statements, and shedding the hierarchies of the “known” versus the “unknown” artists. It deepens my understanding of image-building being similar to writing – creating sentences through visuals that allow the viewer to often uncover their own shifting memories.

Sylvia Schedelbauer / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Sylvia Schedelbauer / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Interestingly, while conversing with Bunu and Sadia about their intentions of putting together a show that spills into the crevices of multiple spaces across the art centre, they hope that the viewers won’t see the works in isolation, but rather in clusters. “Drawing from the idea that Raqs Media Collective who were part of the previous iteration talked about, when you dip your hand into the ocean to pull out a seaweed, there is a whole bunch that emerges and not just a singular seaweed. It’s not one or the other, it’s the coexistence of different and complex stories, thoughts, and perceptions,” they elaborate.

The ensemble of artists and collectives in the exhibition includes Aishwarya Arumbakkam, Vinita Barretto, Uma Bista, Dolly Devi, Shaheen Dill-Riaz, Pooja Gurung & Bibhusan Basnet, Alana Hunt, Ipshita Maitra, Farah Mulla, Nida Mehboob, Jaisingh Nageswaran, Ali Monis Naqvi, Gaurang Naik, Sarker Protick, Sathish Kumar, The Packet, Priyadarshini Ravichandran, Rajee Samarasinghe, Suneil Sanzgiri, Sylvia Schedelbauer, Prasiit Sthapit, Maryam Tafakory, Avani Tanya and Zainab, along with a citation of Dayanita Singh’s Sent A Letter and site-specific notations by Sohrab Hura.

Uma Bista, Nida Mehboob, & Jaisingh Nageswaran / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Uma Bista, Nida Mehboob, & Jaisingh Nageswaran / Photo © Sohrab Hura

For Bunu and Sadia, the transformation from artists to curators also meant leaning into the unexpected process and cycles that exist within the shift. It prompted them to base their core ideas on themes of decay, nurture, pollination, desire, season, and memory-making, which all seem cyclical. Along with the threads that bind the practices together, emerged the need to soften their physical and mental density within the space. The lightness is apparent in the design process, where Sohrab brought in the usage of pins, masking tape, and handwritten text by each individual artist, in place of frames or structured designs which would seem rather heavy.

It’s because of the free-flowing and intentionally scattered imagery across the walls that the stories continue to flow, drifting between the distances that exist between the spaces and the structures that hold them. Since the exhibition has consciously avoided a “starting point” so-to-speak, I walk past the initial galleries to begin my viewing in Sunaparanta’s indoor courtyard that is strewn with fallen leaves and mellow light. It is the sun that brings me there, along with the sounds of the sea that echo from speakers in the adjacent gallery. A letter taped loosely to the wall flutters solitarily.

It’s addressed to “Pyaar Ammi,” and almost instantaneously I’m conjuring up the gentle voice of a narrator whose gaze resounds with the same softness. The work titled ‘Jahan,’ is photographer Ali Monis Naqvi’s attempt to find home beyond a geographical location, while he continues to look for traces of his childhood in Chamanganj, where he lived until the age of 17. While the images are whisps of poetic consciousness collected during his shift to Goa, and other travels, the viewer is also allowed a glimpse of Ali’s family history through single images of his grandparents and his mother’s childhood.

“Ammi by Abba” reads a handwritten caption in pencil near his grandmother’s portrait during her younger years. The three words, while seemingly straightforward, are telling of who lies at the center of his work – a tribute to his Ammi who passed away in the winter of 2020 due to the Covid-19 virus. The imagery and text are a hauntingly nostalgic conversation that he attempts to have with her that recounts the ghettoization of his town, his stark recollection of her lessons surrounding plants and animals, and the hope that she’s watching over him as he holds her presence close.

Much like the unanticipated images that catch your eye as you move through the length and breadth of the exhibition – surprises hidden in plain sight – unexpected emotions find their way to the surface of a suddenly broken heart. Ali’s words make me think of the passing of my grandfather during the early months of the pandemic, which oddly doesn’t seem so distant, and still lightyears away. It makes me wonder – how many protagonists must exist in a single letter? Who continues to live on in the memories of another? The cycle is infinite.

Vinita Barretto / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Vinita Barretto / Photo © Sohrab Hura

With the combination of sound, visuals, drawings, and words, the exhibition eponymously grows out as a tree, that is held together by the same bark, but carries a multitude of branches. While Ali is coming to terms with the idea of home being metaphorical rather than physical, the sound of the sea calls me to Gallery 7, which houses the video diary of Vinita Barretto, who invites us into her physical home with scenes that ricochet between hopelessness and optimism of her every day. Having lived with a father who is diagnosed with depression and bipolar disorder, and a mother who bared the burden of protecting her family from the fallout of the illness, Vinita’s film Knotted, intersperses between color and darkness, much like the crests and troughs of her mind.

Gentle light lingers amidst stark contrasts of a mother braiding her daughter’s hair, of the similarities that bind their skin, and the unintended weight that Vinita now shares with her mother. Moments of respite exist in scenes with the animals that inhabit her space, and the landscape of Goa, which she sees as a portal of peace in an otherwise suffocated body.

The fragility of memory and the attempt to bind it together in tactile form is noticed in the works of Ipshita Maitra, whose installation, Once Was Home (2018), navigates the loss of her neighborhood in Goa, as she sees it transform from a quiet suburban corner bearing markings of a village into a coveted piece of real estate. She elaborates, “While working with prints, I wanted them to feel harsh and fragile at the same time, as if they had been violated and yet preserved for posterity, as if one had managed to reassemble all the fragmented bits, but the cracks were still gaping.”

The delicate artwork prompts feelings of both resistance and resilience; a preservation of the physicality of home by protecting its memory. The structure seems like a puzzle that is simultaneously building as well as breaking through photo emulsions and wired mesh, which act as metaphors of piecing together loss. She questions it beautifully in the words, “how does one express all the emotions one has experienced through a mere gesture?” The act of cutting up her own images speaks volumes.

Sarker Protick / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Sarker Protick / Photo © Sohrab Hura

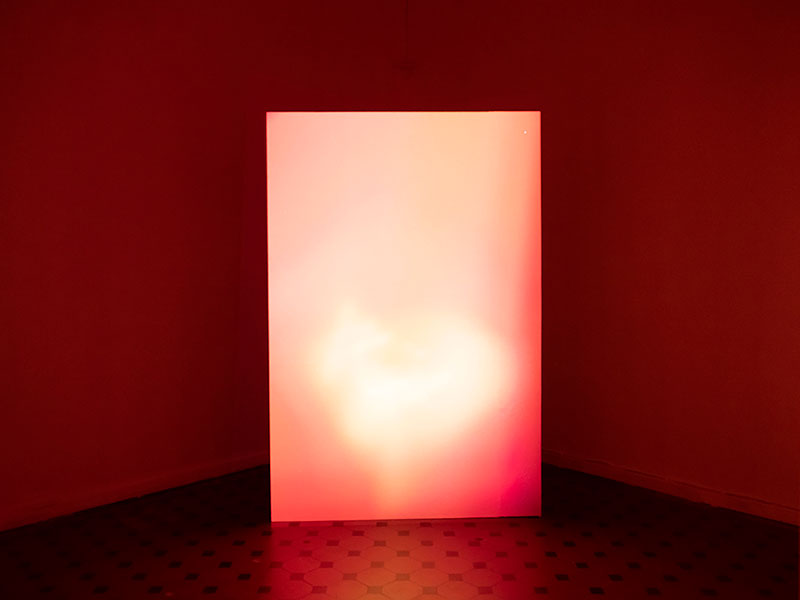

Close by, memory is cloaked in an abstract form painted in sound and light. In a video projection entitled Lohit, photographer Sarker Protick creates a hypnotic experience in a darkroom, using distorted soundscapes and light as a shifting protagonist. Here, one can both physically as well as metaphorically place oneself within the work in the form of the shadows that appear when the viewer confronts the screen. Fleeting memories find themselves within Sarker’s ambiguous patterns, acting like magnets drawing the body inwards. Inhale… exhale… time loosens itself considerably as the viewer is caught in a trance between the artist’s consciousness and one’s own.

The impressions of memory travel and seep through the concrete, finding themselves nestled in a porcelain memorial created by artist, Avani Tanya. As I stand in front of her, she animatedly moves her objects around in a large cabinet that is filled with relics that mirror knick-knacks that surround her home and garden. She explains, “Sometimes when you look at something and then quickly look away, there is an afterimage left behind.” Using the translucent and seemingly delicate malleability of porcelain before it is fired, Avani gives form to this transitory feeling and the preceding memory attached to it, created in the absence of language.

Watching Avani play around with the objects feels like she’s rearranging her own fragmented memories, which funnily have decreased in number because visitors might have taken a few from the exhibit. “I guess your memories now live alongside their own,” I say as Avani smiles rather contentedly. In the same room, reams of paper screech out of a dot matrix printer, stringing together a series of observations made by each artist who is a part of The Packet collective. The papers spill onto the flooring of the room, adding to the tangible memory box of the four walls.

Avani Tanya & The Packet / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Avani Tanya & The Packet / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Alongside the personal, lies the political, witnessed in the sensitive handmade book by Prasiit Sthapit who explores the settlement of Susta, which is a disputed territory between Nepal and India. Then the politics moves even closer, as a single still from Kashmir by photographer Zainab immortalizes this scene – “Then three gunshots echoed across the orchards, even before Zuhr Azaan would be heard in Turkawangan, Shopian, and soon rumors and snapped internet fueled fears.”

In two completely different rooms located far apart, the politics continue using lighter threads explored in films by Nida Mehboob and Maryam Tafakory. While Nida navigates the sexual exploits of Pakistani women through voiceovers embedded against visuals of men showcasing their machismo, Maryam’s film, Irani Bag (2021), is a split-screen video essay that showcases the use of a bag as a tool to “touch,” by piecing together scenes from films in post-revolution Iranian cinema. One can’t help but chuckle at the treatment of both the works, which effectively negotiate the weight of patriarchy and the sensitivity towards public intimacy.

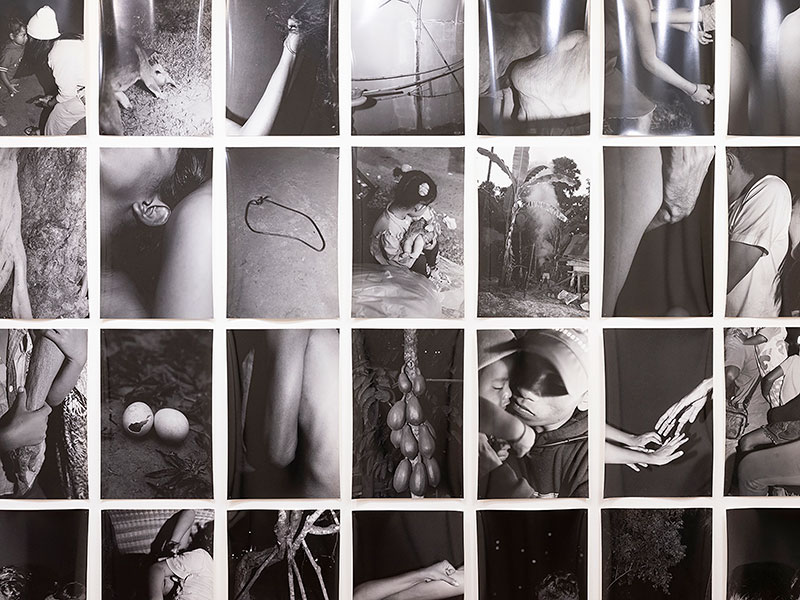

Fragments of touch, or rather the lack of it, find form in the visceral imagery of Priyadarshini Ravichandran, whose square prints are interspersed with limbs and arching bodies reaching out to one another. The images are her confrontation with a strained sibling relationship that questions the fragility of blood ties and the conditionality of bonds. An ambient thumping from scattered speakers descends into the space, assembled by multimedia artist Farah Mulla whose sensory installation unknowingly provides the background score for Priyadarshini’s introspections.

Suneil Sanzgiri / Photo © Sohrab Hura

Suneil Sanzgiri / Photo © Sohrab Hura

As I move in and out of the darkened rooms hosting films by Suneil Sanzgiri, Sylvia Schedelbauer, and Pooja Gurung and Bibhusan Basnet, I continue to see the traces of identity and letter writing that has now shed its literal form to become something more immersive. Bunu and Sadia also point out that the light shifts according to the subject matter on display, adding to the allure, like in the work of Rajee Samarasinghe, for instance, whose film that helms elements of trust and openness is deliberately projected in a workshop space where soft light spills through curtains, blending in with the light captured in the film.

The mind and body meander through a multiverse of worlds while walking through the show; sometimes literally stretching along to view images pasted high up on once blank walls. The art is not independent of the space, but rather an extension of it – a thought that is apparent in the terracotta-tiled roof built by Gaurang Naik that lies in the open-air platform of the Center. Inside, figurative sentences started by one artist are finished by the next, creating a book of letters all addressed to the seeker of these stories. And so, the pattern continues from photographer, to curator, to viewer; relaying the thought that photography, as a medium, is anything but solitary.

[All photographs above are courtesy of Sohrab Hura, who holds the copyright.]

Copyright © 2023, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Zahra Amiruddin is an independent writer, photographer, and professor of photography who has been working in the field for nine years with a specialization in visual practices and contemporary art. Apart from being featured in national and international publications, her main areas of interest include ethnographic studies, astronomy, personal narratives, and family histories. She has shown her work in solo as well as group exhibitions across Greece, South Korea, Indonesia, and India and is currently developing a collaborative project with Eight Thirty, a women’s photography collective. Her work was published as the supporting text in Between Doors, a photobook about North Korea.

Copyright © Zahra Amiruddin

Copyright © Zahra Amiruddin

20 November