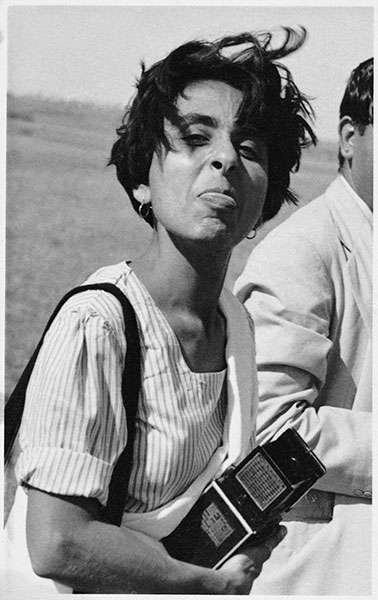

Homai Vyarawalla with her Speedgraphic Camera (Photographer unknown.)

“Why Not?” This was Homai Vyarawalla’s response to my question to her a year earlier, “If they invite you, would you be willing to travel with me when I give my talk at Harvard next year?” I wasn’t entirely surprised with the answer given by India’s first woman press photographer on that hot and humid evening because being adventurous and open to new possibilities has always defined the contours of her eventful life. Beginning a career in 1937 with pictures of a women’s picnic at the JJ School of Arts in Bombay, Homai Vyarawalla was to become a significant chronicler of early nationalist history when she moved to Delhi in the early ‘forties. An employee of the British Information Services, Homai was allowed to free-lance, and she traveled all over the country on assignments; to the ravines of the Chambal Valley, on cranes high above the Bhakra Dam, trekking through the jungles of Manipur and hitching rides in Sikkim where she shot the first crossing of the Dalai Lama to India in 1956. Strangely enough, she had never been abroad and at age ninety-five, this would be her first journey outside the country. For a start, we had to get her a new passport and medical insurance. To make the long journey comfortable, Harvard University could be persuaded to pay for one business class ticket, but we would have to sit separately. There was also the business of getting a visa in a post-9/11 scenario. With mandatory biometrics, Homai would have to be fingerprinted in a different city from mine. In the months leading up to our travel, I still recall a conversation with one of her relatives who pointed out that I would be traveling with her at my own responsibility. I had defiantly replied, “She has never been abroad before. If she wants to do it now, who are we to stop her? I will certainly not regret it.” I wondered if I had spoken too soon.

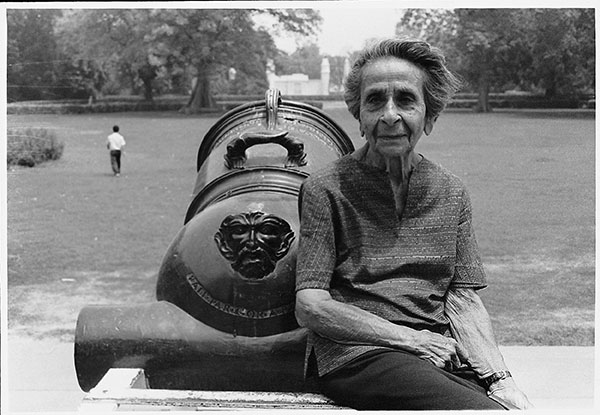

Homai Vyarawalla at Teen Murti House, 2001 (Photo taken by Sabeena Gadihoke.)

The Gateway of India, Bombay, late 1940s

Travelers at the Mole station near the dockyard in Bombay, late 1930s

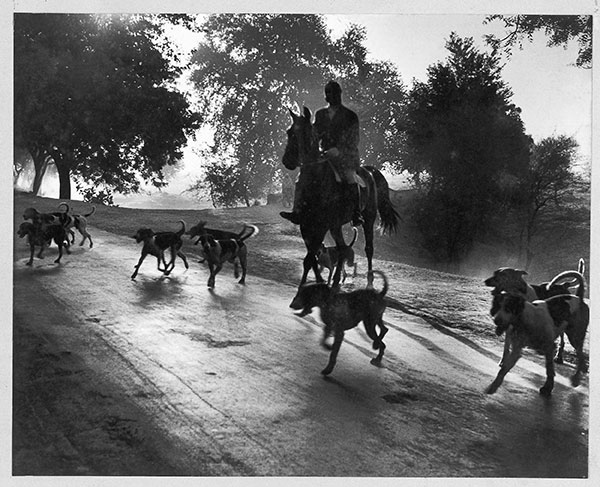

A Fox Hunt in Delhi, early 1940s (This is one of Homai Vyarawalla’s favorite pictures.)

A Fox Hunt in Delhi, early 1940s (This is one of Homai Vyarawalla’s favorite pictures.)

I had first met Homai Vyarwalla in the summer of 1997 when I started to film my documentary, Three Women and a Camera made on her along with two younger photographers. It was a search for a legacy of women operating the camera in India that became a more detailed body of research to locate other forgotten names in history, finally culminating in a book. After a rich career spanning three decades, Homai who had photographed Parsi Bombay and its suburbs in the ‘thirties, the trials and tribulations of the political nation in the making and subcultures of social life in the city of Delhi such as events at newly formed embassies and the elite gymkhana club, marriages, school functions and fancy-dress parties, gave it all up one day in 1970. It was a simple act. She just “capped her lens.” To understand this rather abrupt decision would require a reassessment of the euphoria of an entire generation fired by independence and its subsequent disillusionment with undelivered promises during the two decades that followed.

Homai Vyarawalla and her colleagues at a photo session with Indira Gandhi, late 1960s

(Photographer unknown.)

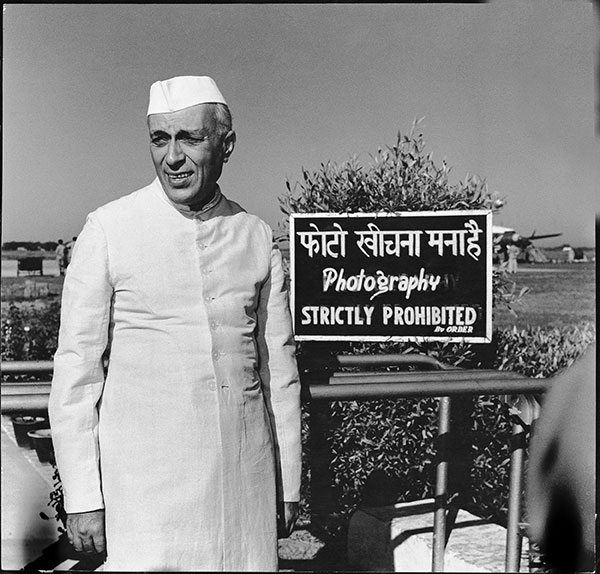

There were many photographers like Homai in Delhi in the ‘forties and ‘fifties. They were all in the same place, at the same time, photographing the same charismatic ‘leaders’ and grand political events. Many of them photographed the pageantry of independence and the crowds at Red Fort when the flag was unfurled for the first time. They also documented the building of dams, steel plants and educational institutions. Nehru was their favorite subject, ever ready to perform for their cameras. Among Homai’s well known pictures is a spontaneous image of Nehru hugging his sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit on her arrival at Palam airport in 1954. There is also a more deliberately posed picture taken a few minutes earlier as he smiles against a board saying, “Photography Prohibited.” If you hunted deep in the archives of these photographers, you would eventually discover other kinds of visual histories, some of them mainstream and not so euphoric, others not so mainstream either. One such example is a Congress Working Committee meeting held in mid June 1947 when leaders like Nehru, Patel, and Rajendra Prasad voted by a show of hands to ratify the June 3rd plan to partition India. Homai Vyarawalla was present at this meeting along with photographers P.N Sharma and Kulwant Roy, where in her words, “some decided the fate of all of us.” These pictures never became part of our collective visual memory of partition.

Jawaharlal Nehru at Palam Airport, 1954

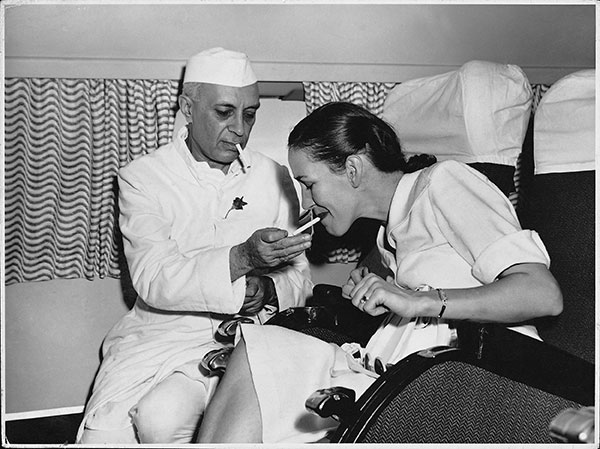

Prime Minister Nehru with Mrs. Simon, the wife of the Deputy High Commissioner of Britain

(Photo taken aboard India’s first BOAC flight to Nanda Devi.)

As the years went by, Homai and her contemporaries were witness to all kinds of changes. They saw streets being renamed, a more conflicted parliament, the deaths of Gandhi, Patel, and Nehru, several wars, language movements, and the other edges and contradictions of Nehruvian modernity. They also watched a different work culture emerge in their profession. The intimate relationship between photographer and subjects (Nehru knew many of them by name) was no longer possible. Press photography was to become more crowded and Homai would often find herself at a loss in the more belligerent ‘sixties prompting B.R. Ambedekar to once inquire, “How did you get into this rough crowd?” The space of the “gentlemen photographers,” as Homai liked to describe her colleagues, was to be usurped by a new generation of camera persons. A lament about the older order changing was to spread all over the country. In 1959, the sensational Nanavati case, where Commander Kawas Nanavati shot dead his British wife Sylvia’s lover, Prem Ahuja, prompted resentful letters to the Editor in Blitz about the “lack of culture and values.” Among many other conflicts, the Nanavati trial was also representative of a struggle between the old elite of Bombay, the Parsis and the new Sindhi upstart (that Ahuja represented) now staking its claim on the city.

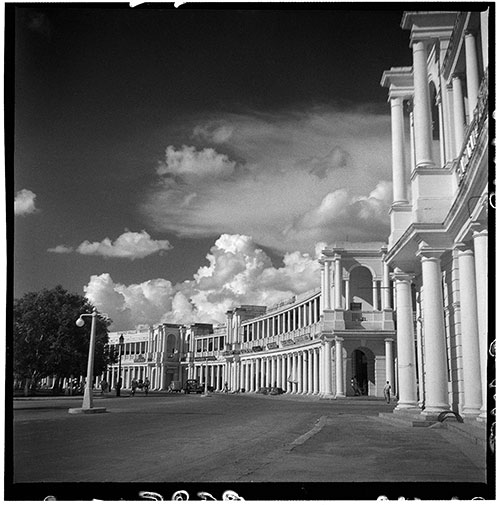

Connaught Place, New Delhi in the 1950s

Connaught Place, New Delhi in the 1950s

The Chhatri at India Gate, New Delhi, with the statue of King George V (It was removed later.)

The Chhatri at India Gate, New Delhi, with the statue of King George V (It was removed later.)

While she shared with others of her generation a general disillusionment with the Nehruvian dream, there were other reasons for Homai moving on. Her long-time partner Maneckshaw had passed away and her only son Farouq now a professor in Pilani. He needed someone to run his home and Homai, who had been a career woman all her life, wanted time off to be a homemaker. She now took delight in doing other things that she had enjoyed but never had the time to do like Ikebana, macramé, and baking. She directed plays with the local women’s club and built a beautiful garden that everyone would talk about. Of course, as the sleepy town of Pilani discovered, Homai could also make tables out of wood, she could build a staircase with cement, and create things of beauty from discarded rubbish. Not many there knew her background. In a history of post independence photography in India where press photographers remained unsung, Homai as the only woman among them was even more anonymous. Living alone and totally self sufficient after the premature and tragic death of her only son in 1988, she once described herself as Robinson Crusoe. The city of Baroda, where she has lived for twenty-five years isolated from the world outside, became her island.

A Fancy-Dress Party at the Delhi Gymkhana Club

A Fancy-Dress Party at the Delhi Gymkhana Club

Homai Vyarawalla with a diplomat after a photo shoot at the Indonesian Embassy, 1960s

Homai Vyarawalla with a diplomat after a photo shoot at the Indonesian Embassy, 1960s

I was reminded of all of this when I found her pottering through her handmade purse on the morning after our talk at the Harvard Inn. I had carried a small video camera with me and as I checked out the controls, there were strange items emerging from her bag. Along with several tools, was a tube of rubber cement to mend her hand made slippers in case of an emergency, some nutmeg and other home remedies for possible illness and a grater to shred hard fruit like apple. She had used that earlier that morning when she had been shocked at the quantity of food served at breakfast. Conversant with ‘American servings’ and with Homai’s measured life and dislike of wastefulness, I wasn’t surprised at that. We had arrived at Boston after a long journey and stopover in London. I had been upgraded to business class along with Homai who had charmed the crew members of British Airways and a couple of co passengers traveling with us. The friendly head stewardess was surprised to know that Homai had been the official photographer for the British High Commission for most of her career. When researching our book, she had often regaled me with stories about upright and graceful employers, many of whom had become her friends for a lifetime. Among Homai’s many such lasting relationships was one with her former Australian boss, Hugh McInnes, a friendship that spanned two continents and sixty years. India had left a lasting impression on McInnes and his last card to her in 2003, from the nursing home where he was admitted for senile dementia read, “To Homai from Hughie who once was in India.”

On the journey to London, I kept thinking about Homai’s reactions at Heathrow. What would she feel to be in the country that had fired her imagination for so many years? It turned out to be quite different from what I had expected. We disembarked from the plane with at least twenty-five elderly Indian passengers, all of whom needed a wheelchair and had to wait for almost two hours in a seedy part of the airport for transport to arrive. There was only one electric cart that could ferry three people at a time. Homai was clearly the most able and as we waited endlessly as the last in line, she walked up to the woman in charge and said, “Madam, this doesn’t speak well for British efficiency.” Clearly the experience at Heathrow was completely at odds with her vision of the dynamic and hard-working employers she had worked for in Delhi. Back to more humble travel during the next leg of the journey from London to Boston, I was woken up by a sparkling Homai who had walked up from club class to slip me some special eats. She had brushed aside all my suggestions about exercises on the flight and seemed to be managing very well on her own. As the cab weaved its way towards our final destination at Harvard Square, I watched her face in the fading sunset as she curiously looked out at the tall Boston skyline. It was a moment I had imagined for months and suddenly all I seemed to want to do was to get to sleep. The next morning was a nightmare. Homai was up bright and rested and I was down with a killer migraine. It was just as my friends in Delhi had wryly predicted!

Sabeena Gadihoke and Homai Vyarawalla at a talk, University of Westminster, London, May 2008

(Photographer unknown.)

Despite migraine misery the talk at Harvard went off well. We would repeat the pattern at Northwestern at Chicago and at the University of Westminster in London. Having Homai with me changed the nature of our talk because there were all kinds of questions, and not just to do with her images. Fifty years apart in age and with different expectations of gender roles, we would sometimes contradict each other. At a packed event in London, asked how she juggled career and family, Homai declared that it was possible because her husband and she shared everything “Fifty-fifty.” I got a playful rap on my head with her stick for asking, “Why then did he not wake up at 4:30 in the morning to fetch the milk instead of you?” She was cheered for calling herself a “bachelor girl” since the death of her husband. Historian Uma Chakaravarty noted how, along with many other women of her generation, she had been photographed by Homai in performative “costumes of India” parties and competitions. Personal collections offered the possibilities of other kinds of visual histories of the ‘every-day’ that provoked conversations about the nature of archives, both public and private.

A significant presence at all our talks was that of Homai’s Zoroastrian community, severely under threat due to a dwindling census in India today. Families of NRI Parsis swamped us at every venue demanding to have photo-ops with “aunty Homai,” and after a while I gave up trying to deny Parsi origins because it just seemed more convenient than to explain how I ended up writing a book on her! It was a time of connecting: For Homai a reunion with very old relatives; for me, with friends whom I had not met for years. After the release of our book in 2006, this was the first time that Homai and I could spend more time together. We would go out for short walks when the weather was good. While being impressed with clean streets and the tulips in full bloom everywhere, I could also sense Homai’s alienation with the lack of human contact in public space. She would often stand at the window in our hotel in Chicago looking at the men working at a construction site below, possibly because it was a reassuring reminder of her noisy and crowded surroundings back home in Baroda. The skyscrapers of downtown Chicago did not impress her either. After half an hour of an extremely informed tour through the city center by South Asianist Kathryn Hansen, who had flown down from Texas just for the talk, she declared that all the tall buildings looked the same! Kathy had specially hired a car so that it would be easy for Homai and I am truly grateful to others like Chris Pinney, Geeta Patel, Joyce Singha Ghosh, and Bhavna Dave for stepping in at all difficult moments on the trip.

On our last stop, we arrived to a grey and foggy London. This wasn’t a surprise as sunny weather is almost always within tantalizing distance but never quite seems to make it there. I took Homai in a slight drizzle to Tavistock Park opposite the hotel where she wandered up to a rather pathetic bronze statue of Gandhiji and declared scornfully that it didn’t look like him because he had no spectacles! She paused at the road for a considerable amount of time and admired the orderly traffic. She seemed to like London a lot better than Cambridge and Chicago because she could see people on the streets. The event at the University of Westminster was special in more ways than one. Our talks in the U.S. had been well attended but they couldn’t match the passionate engagement and chemistry with the audience in London because of the rich nuances of a shared colonial history.

Homai Vyarawalla on her 98th birthday in Baroda, December 13, 2011

Homai Vyarawalla on her 98th birthday in Baroda, December 13, 2011

(Photo taken by Johannes Manjrekar.)

Homai Vyarawalla and Sabeena Gadihoke on Homai’s 98th birthday, Baroda, December 13, 2011

Homai Vyarawalla and Sabeena Gadihoke on Homai’s 98th birthday, Baroda, December 13, 2011

(Photo taken by Johannes Manjrekar.)

As we returned to Delhi and then two days later to Baroda, I took out my camera for the last time and asked what she had thought of the trip. Her cryptic response, “alright” seemed a bit disappointing. Like everything in Homai’s life, the reaction to the trip that I had looked forward to for months, was quiet and measured. “What now?” I asked her. She said that she would spend the next week cleaning the house. She would then get her fifty-five-year-old Fiat repaired. If it didn’t get repaired, she would think of buying the new Nano next year. She brushed aside my continuing apprehensions about her driving in Baroda traffic. She also checked out the new steel baking tray that my class-fellow from Jamia, Joyce, had bought for her in Chicago. It was too big for her oven and she calmly told me that she would cut off the edges with a chain saw! As I left her in peace on her quiet and noisy ‘island’ in Baroda, I wondered about her response. Perhaps there was a right time for everything. Had this been the wrong time for her? And then an image came to my mind: of Homai napping on the bus in London. On the last day of our trip, we had done the touristy thing and taken the Big Ben tour to see London. Homai had been perfectly at ease hopping on and off and while on the bus would slowly slump into a sleep after every half hour which was a pretty efficient way of dealing with all the different time zones we had been through in two weeks. When she awoke, I had been surprised as she seemed to recognize many of the regular sights of London. Suddenly it dawned on me. Sitting in her armchair in Baroda, I realized that Homai Vyarawalla had already traversed the world long before our trip through books, photographs, and satellite television. Like many others of her generation who had never been abroad, she had been an international traveler through a world of imagination. The actual trip then ceased to matter. Whether it was the ‘right’ or the ‘wrong’ time, Homai Vyarawalla on her ‘island’ had already made that journey long before we physically made it.

Homai Vyarawalla (Photo taken in the Chambal Valley by P. N. Sharma.)

This account was first published in Third Frame: Literature, Culture and Society. Academy of Third World Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia & Foundation Books, Vol 1, No 4, October-December 2008.

Copyright © 2021, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Sabeena Gadihoke is professor at the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre at Jamia Millia Islamia, where she teaches Digital Media Arts. She started her career as an independent documentary filmmaker and cameraperson and has written a book on India's first woman press photographer, Homai Vyarawalla, titled Camera Chronicles (2006).

A photo historian and curator, her most recent significant curatorial project was a retrospective of photographer Jitendra Arya, at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai and Bangalore, titled Light Works.

Copyright © Sabeena Gadihoke

20 November