Family photography and personal archives have always interested researchers as well as collectors. This fascination comes not from their artistic or aesthetic quality but from the density and richness of information that these unremarkable or ‘common’ pictures, seem to provide. Personal photos are a part of a complex network of memories and meanings, which could offer insights into the lives that they have recorded. Photography within the home has undergone major changes in the past two decades. The move from analog to digital has offered more access to the camera, particularly in a part of the world where photography was an upper-class pursuit. The smartphone has a ubiquitous presence in our lives today, allowing for the capture of fleeting and ephemeral moments of everyday life with greater ease. In this short essay, I attempt to reflect upon two forms of documentation of my family – one analog and the other digital – separated by half a century.

I was born in Allahabad U.P. on the first day of 1966 in a modern, middleclass Muslim family. All three adjectives have a special significance and meaning quite different from how they would be defined today. Modernity was gauged by the thought and scientific temper you had nurtured through education. The term ‘middleclass’ comprised of educated professionals who dreamt of contributing to the building of the nation state at the behest of India’s first Prime Minister Nehru who urged citizens to break away from an old feudal social order that had prevailed for centuries. The term ‘Muslim’ too had a very different connotation from what it means today, in a moment of right-wing politics and media-hyped Islamophobia. Emerging out of the legacy of an Indo-Persian tradition that had roots in the rebellion of 1857 against the British, the generation of my parents were nurtured by their knowledge of progressive Urdu poetry and prose. My mother, Rehana Bashir, was a successful practicing gynecologist for over sixty years. She acquired her medical degree in 1953, from the then Lady Hardinge Medical College, (now Sucheta Kriplani Medical College), New Delhi, and my father, Ziaul Haq, was a journalist with affiliations to the Communist Party of India (CPI), whose membership he acquired as a twenty-year-old at the height of India’s freedom struggle.

Left: My mother holds her medical school graduation photo, 1953.

Left: My mother holds her medical school graduation photo, 1953.

Right: Rehana Bashir & Ziaul Haq together in the winter of 2020.

Later he worked for the official newspaper of the CPI, New Age, in Delhi. Like Salim Mirza, the protagonist essayed by Balraj Sahni towards the end of M.S. Sathyu’s iconic film Garam Hawa (1974), my father too chose to stay back in India despite the fact that his entire family had moved to Pakistan. Ours was an unconventional household, where my mother was the main provider while my father devoted himself full time to the CPI without any expectation of remuneration.

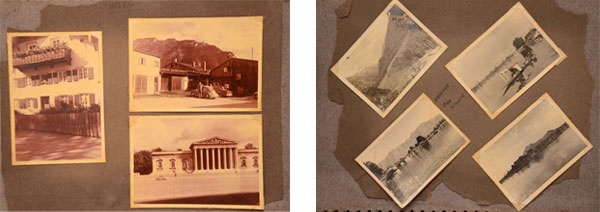

In 1957, my mother went to England for her post-graduate medical studies. On the eve of her departure her father gifted her an Agfa range finder and she used this to teach herself photography in far-away England. This meant that Rehana had made many images till her return to India in 1959. These early albums give us insight into a different Rehana. One who loved to travel in Europe or India’s “Switzerland” in the 1960s – Kashmir – where she went on a holiday with two other friends. She brought back some picturesque views of landscape from these trips.

Left: Europe as seen through the lens of my mother in 1958.

Left: Europe as seen through the lens of my mother in 1958.

Right: Picturesque landscape of Kashmir photographed by Rehana Bashir, 1960.

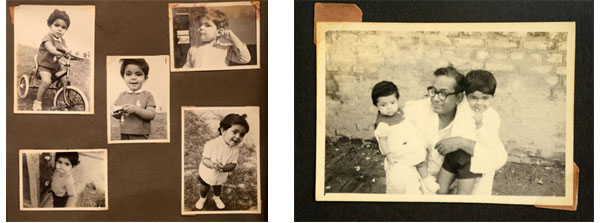

After her marriage this landscape changed. I, her first born, became Mother’s favorite subject. She was going to chronicle the family that she had just started, using me as a backdrop.

Left: My mother starts to chronicle her family with the birth of her first child, 1966.

Left: My mother starts to chronicle her family with the birth of her first child, 1966.

Right: The boys of the family are photographed by the lone female photographer, Rehana, 1970.

While she may not have ever been so carefree later in life (would our mothers have had different lives if they had not been our mothers?), the fascination with travel continued well into her family life, be it short getaways for day picnics, longer trips to Himalayan hill stations, or an eventful journey to South India in the late 1970s. I say ‘eventful’ because it was marked by a rather unfortunate episode. There were no photos of the Southernmost tip of India because I dropped the precious Agfa camera into the sea while attempting a sunset picture at Kanya Kumari!

The sixties and seventies were a period when photography studios were still an important space for personal photography. Despite owning a personal camera, we too often used the services of studio photographers to make ‘better quality pictures,’ especially on special occasions. As the ‘lady doctor’ who wielded a camera in Allahabad, when it was considered a male preoccupation, my mother was looked upon in awe by the studio photographers. Mr. Rashid owned the studio we went to that was named Flash Lite; I have a vivid memory of my first visit to Flash Lite, where our family was photographed with an early SLR camera. Rashid was busy setting up his equipment, but I was transfixed by the rather large wooden contraption mounted on a pedestal in this small studio space. The camera that had a metal barreled lens was even more of a mystery to my ten-year-old eyes as it was partly obscured by a black cloth. Clearly it had not been used for years. I always tried hard to get Rashid’s son to show me this old bellow camera, but sadly his answers to my queries were always vague. Rashid’s wife was also a patient of my mother and so he gave special attention to this client and was always in attendance to come home and photograph visiting relatives as well as our birthday parties. These public occasions when an ‘expert’ took portraits were usually annoying, as our attention was on the gifts and friends. Instead, we were being asked to be still and being directed by Rashid or my mother for the perfect picture. I often wondered why Mother asked Rashid when she was perfectly capable of clicking good pictures. Perhaps she wanted to be in the frame for the memorable occasion or not risk missing a good quality photo taken by him.

Mother helps me cut my 3rd birthday cake. Photograph by Mr. Rashid, January 1969

Mother helps me cut my 3rd birthday cake. Photograph by Mr. Rashid, January 1969

Of course, children rarely have a say in the way that they are photographed by parents, or perhaps it might be better to say that parents often project hidden desires while picturing their children, much to their embarrassment years later. My younger brother who was a pretty (read fair) baby as a child was made to wear a frock in one such photograph as a reminder of the daughter that my mother so desperately wanted after her first-born son.

The analog moment is rich with what scholars have termed ‘materiality’ – the idea that, while photographs are images, they are also objects which have their own significance for the person dealing with them. The richness of my mother’s documentation was not limited to just taking pictures. She was equally invested in organizing and cataloging the material carefully in photo albums, giving it order so that one could enjoy the photographs and not allow them to be scattered. Each print stuck neatly in the photo album almost half a century ago was not just a photo chemical trace of our lives, but also an artifact with texture, whether on glossy or matt paper that slowly aged with time. The prints in the albums were accompanied by descriptions carefully written below or on the reverse, becoming as much a part of the memory as the photograph itself.

These organized family albums and my mother’s photography have been an amazing legacy for me, once I eventually chose to be a photographer and a teacher of photography. The many family albums at home still draw me irresistibly towards personal archives. They have unlocked for me two kinds of memories that go back by half a century. The first relates to the family and moments of leisure with friends.

A close friend, Pushpa, photographed at an ancient temple near Allahabad by Rehana Bashir, 1956.

The second, and equally important, emerges from my interest in the history of my hometown. Allahabad holds a significant position in the social, cultural, and political life of the formative years of independent India. With its famous university and High Court, it remained the nucleus of a certain intellectual and social sphere that was coveted. My parents had a brush with this life and their photo collection gives us glimpses into this. Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s trip to Allahabad in 1983 is a part of our photo collection, as is Kaifi and Shaukat Azmi’s visit during the golden jubilee celebration of Progressive Writer’s Association in 1987.

As the life well lived by my parents – who were born at the two ends of the 1920s – comes to a close, there are new memories to make. My parents are greatly dependent on caregivers for their day-to-day needs. I always traveled every fortnight to Allahabad by the overnight train to check on them, but the Covid 19 Pandemic brought a new kind of urgency. When the lockdown was declared, I drove 12 hours alone to reach my parents and was with them for the entire year. As I facilitated their day-to-day care, I got more time to spend with them. In a somewhat more detached way, I also had more time to observe them as a photographer. I see this phase of their life as a second childhood. The photographer in me searched for intimate moments that were not necessarily happy or perfect but precious and could be lost forever.

I photograph my parents in the summer of 2020 when my mother is unwell.

Caregivers attend to both the parents and I take care to include their pet in the frame, March 2020.

Caregivers attend to both the parents and I take care to include their pet in the frame, March 2020.

As a child, my brother and I were the subject of my mother’s gaze through the viewfinder of the Agfa camera, and now my Nikon or mobile phone looked back at them. To capture my father getting a shave or to catch my mother’s expression while enjoying her favorite dessert is a project that I pursued with zeal. My most pleasurable moment has been when I have been able to capture their intimacy, for instance while unconsciously holding hands.

I made this picture on my parents’ wedding anniversary in 2018.

One cannot deny the discreet yet intrusive nature of a slim mobile phone camera that makes it possible to be ubiquitous and capture the fleeting moment. And yet, this experience has made me think more deeply about what eludes the camera and what photography is not able to capture. These include the painful moments of old age that my camera could witness during the lockdown. Recently, my mother was quite unwell and in pain. While capturing some of her vulnerability and helplessness I still rushed to draw the camera more when I saw any momentary relief in her expression or her smile at seeing me first thing in the morning. These may be the images that I have shared in public to reassure others that she is better than before.

My mother loved the attention and importance she got from admirers

on her 90th birthday, January 2020.

Photograph by Sohail Akbar

My mother created ideal vignettes of her domestic life as a family woman. Her pictures were not unlike the Kodak advertisements of the time that reflected the aspirations of the middleclass family and its parameters of ‘success.’ I see my own practice documenting my parents as a more complicated engagement with this idea of perfection. As I photograph my aging parents to preserve their memory, I do not shy away from recording their not-so-easy moments, like struggling to bathe or being fed in bed, because concealed behind the veneer of happy family pictures is a whole universe of material and lived experience which is difficult, labored, and not always pleasant.

Left: Father undergoes ‘dry cleaning.’ Photographed by me in summer of 2020.

R: Poonam, my mother’s caregiver, was devoted to her wellbeing and ensured that she looked good.

Photograph by Sohail Akbar, 2020

Father enjoys his favorite Ghazal of poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, sung by Iqbal Bano ‘Hum Dekhenge.’

Father enjoys his favorite Ghazal of poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, sung by Iqbal Bano ‘Hum Dekhenge.’

Photograph by Sohail Akbar, August 2020

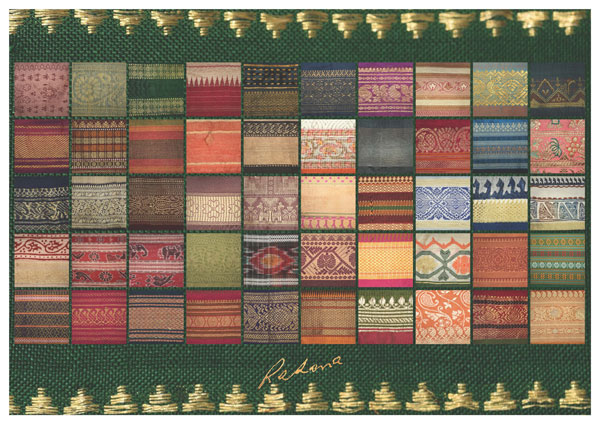

I do feel that digital photography and the intimacy afforded by the lockdown (as opposed to the isolation faced by many), gave me the opportunity to push this project further. The possessions, strewn around our home bear witness to rich and fulfilled lives lived for nearly a century. There is my mother’s love for sarees and her collection of curios through her various travels.

An artwork created by combining photos of 50 saree borders belonging to my mother.

Photograph by Sohail Akbar, summer 2019

My Communist father’s love and passion for history, literature, and poetry resides in his overflowing library. I photographed stacks of precious books but also memorabilia documented in letters, cards, invites, diaries, and address books, as I attempted to capture their musty smell in my images.

These two collections of documentary photographs, set fifty years apart chronicle the journey of my family. The two are similar and yet different; one presenting the happy family within the established norms of the personal album, and the other reassessing the same family by trying to come to terms with the fragility and mortality of my parents.

Comrades gather to wish Ziaul Haq on his 100th Birthday on 28th September 2020.

Photograph by Sohail Akbar

Postscript: After this essay was written, both my mother and father passed away peacefully in October and November 2020, within a gap of forty days. As I browse through the thousands of digital files of photographs made of them, I am lost. The sheer volume of pictures scattered over phones, my laptop, and many hard drives overwhelms my sensibility as they keep appearing unannounced either as a memory, on social media, or in searching for something else on one of these devices. Unlike my mother’s chosen and neatly arranged pictures in albums that allow for clear memories, I try to make sense of these ephemeral moments and to stay with the feelings associated with them. At times these images give me solace and occasionally, to put in the words of Roland Barthes, “They have an element that shoots out like an arrow that pierces me….”

Copyright © 2021, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Sohail Akbar was invited to write this essay for PhotoSouthAsia by our Guest Editor, Sabeena Gadihoke. We encourage you to begin with Gadihoke's introduction, The Family and the Self in the Time of the Pandemic, and to also read Gadihoke's other invited essayists:

Surayanandini Narain: Home Reimagined: Photographic Archives of 2020

Farjad Nabi: 700 Wings of Love

Copyright © Sohail Akbar

Copyright © Sohail Akbar

Sohail Akbar teachers still photography at the AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia University, New Delhi. He also practices and researches photography. His areas of interest include personal photo albums and family archives. Akbar is also a practicing photographer who has photographed extensively for the development sector in India. He has exhibited in two solo exhibitions in Delhi. Nazraana: A Tribute to Life is a photo book of his collection of work.

Akbar lectures and conducts workshops on photography at various institutions in the country and has contributed to the development of curriculum for courses that teach photography at school and university level. He has recently diversified into bird photography and is using his skills to create awareness of bird life amongst young enthusiasts.

20 November