Photograph © Hemant Sareen

The sudden intimation of mortality the pandemic forced on us, has me thinking of the fate of the family photographic archive. The family archive that constitutes old legal and personal documents, my grandmother’s clothes and jewelry, old toys and artefacts, and photo albums accrued in the last hundred years. Despite its relatively modest size, its saliency has only become keener to our dwindling numbers. Feeling the effects of forced isolation, I thought revisiting the photo archive in that intense moment being experienced around the world by humans and non-humans alike, would be conducive to engaging creatively with the family history. Yet, leafing through the photo albums after a long while, felt like a self-invitation to a séance, where I am both the sole attendee and the medium. Instead of a single, clear voice, I had channeled a crosstalk of half a dozen voices of family members, both living and deceased.

This babel surrounding the family photographs is what Marianne Hirsch calls a “verbal overlay,”[1] a persistent presence of other gazes from the past that have claimed the photograph as their own. There are other kinds of voices associated with photographs, some intrinsic to it. Fred Moten ascribes a “phonic substance”[2] to photography, positing it as a challenge to the “ocularcentrism,” that informs the predominant discourses on the nature of photography and even our experience of photography, and to the “semiotic objectification” of photography where reading and interpretation of signs in turn marginalizes photographs’ “phonic materiality.” Although Moten’s proposal comes in the charged political context of racial violence and the questions of ethics and aesthetics of displaying brutalized black bodies, it enjoins us to be receptive to the photographs’ larger affective potency and embodied experience of the photographic image beyond visual and haptic.

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

The earliest persistent likenesses captured on light sensitive medium seemed to trap the subjects behind a glass pane that shut in the sounds. The sound and image, parsed thus by technology, have ontologically refused to be severed from each other. Kaja Silverman reminds us, paraphrasing Walter Benjamin, that photography is “the primary means through which the world discloses itself to us.” “What [photography] reveals is uninformed by human consciousness – not just because it exceeds our optical capacities, but also because nature ‘speaks’ a different language to the camera than it does to the human eye: one based on analogy.”[3] Language both as text and spoken word are imbricated in the photograph. Language helps to infuse the “analogy,” which the camera produced, with human consciousness whenever people give in to the irresistible urge to talk about images. Families sit together around family albums to reclaim through the spoken word, the world revealing itself in the photographs, as theirs. In the process, families reinforce their affiliations through “various relational, cultural, and institutional processes – such as ‘looking’ and photography.”[4] Hirsch’s use of the word ‘looking’ in quotes suggests an expanded sensory range, like Walter Benjamin’s “habituated physiognomic knowing,” an instinctive awareness that is used to negotiate a living space only partly through vision.[5]

***

Being not only the youngest child, but also one who came into self-awareness in circumstances far removed from my siblings’, I would always need to be filled in on what had already passed. There is an image in my mind of mother huddled with her children, the oldest of whom was barely in his teens, together pouring over the albums. These interactions went on for years over repeated viewing of family albums, and often without the albums. These exchanges ranged from gentle conversations to hushed, somber contemplations about probable what-if arches of family history. The complexity of exchanges in this Agon-like space the photo albums created, belied the young age of my siblings. There was a noticeable lack of sentimentality in these collective confabulations during the viewing of the albums. This was very clearly part of my mother’s aesthetic ethos that chose the poetic, or the pragmatic, depending on the situation, over the emotional. The exercise was in sociability, of relating to family as substitute for the larger world. Together they talked the photo albums into divesting themselves of some of their reticences.

There were certain recurring readings of the history of close relatives, especially my mother’s five sisters’ individual and collective stories were often revisited by my mother along with and at the instigation of her three daughters. Much of the family history was filtered through the four women and its narrative and counter-narrative remain associated with their voices. The photographs are covered in palimpsest of their oral annotations, echoes of collective and individual (re)readings, often questioning the archive’s narratives, and problematizing over the years what were once simple facts that easily coincided with the indexicality of the photographs.

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

Our ever-evolving relationships with the family photo archive have been simultaneously intimate, objective, and discursive, fetishizing as well as detached, pushed and pulled in several directions by dominant voices that emerge from the clamor before being subsumed by it. Initially Mother’s memory was the key to our past and remained so at least for pre-Partition memories, which were strong childhood memories, like the names of places, of her route to the school, of landmarks in the neighborhoods she lived in. Her existence was at once in both the temporal and the visceral geographies.

Later she had her older children helping her with recalling details of name, place, time, occasion, related to photographs in the albums. The hierarchies would vanish all together and memory would become contentious. To a lesser degree for our mother – she often shared her admiration for tones, depth, and detail in the photographs – but certainly for my siblings, the family photos were only notionally material. Rather they were events forever unfolding somewhere between “live performance and mechanical reproduction”[6] serving as nodes within lived and oral histories, even verbal images or descriptive analogs that were used as citation or allusion during discussions.

For me the photographs were solid objects, at once evidentiary of the past, in which I had just a cameo appearance, as they were visions of modernity, of future, that defied the photography medium’s melancholy. What was shared though were the anxieties of forgetting to remember, about forgetting and being forgotten, in life after photography, of being bereft of the deeply involved and reassuring gaze of the camera.

My siblings and I were supposedly the “hinge generation,” a phrase Hirsch borrows from Eva Hoffman while writing about “postmemory,”[7] to whom first-hand knowledge of the trauma of the Partition, the subsequent dislocation, relocation, and rehabilitation, would be passed onto. Yet all of us had different capacities to absorb this knowledge. Still, it was not the trauma, which remained largely understated, but its consequent effects, that were our given circumstances or fate, that would continue to mark us for the rest of our lives. My siblings, at my father’s early death, lived through perhaps as traumatic a rupture in their lives as their parents and their grandparents did in 1947. And both traumas are mirror-images of each other in the way they were acknowledged and repressed.

***

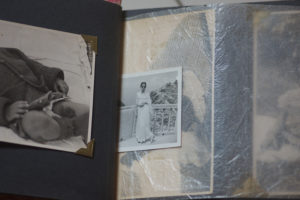

The albums were fastidiously organized till their abrupt conclusion many months before Father’s death. Updating them was an event. I imagine a table strewn with photo prints fresh from a photo studio, scores of photo corners that would hold the photographs and my mother and father discussing the arrangement of images on the page. The largest of the albums was truly the family album. It records the family history in independent India. It’s bustling with images of my parents on their honeymoon, children, close relatives, picnics, excursions, small celebrations, and scores of candid moments.

A photograph of me at around a year and a half, looking perplexed in a hounds-tooth suit and a bow tie, sitting obligingly on a rocking horse, reveals the “multiplicity and mutuality of looking that composes all family pictures.”[8] I can almost hear my mother asking my father to double check the aperture or ask me to look up, or my siblings watching me being the center of attention, some with a tinge of envy, others indifferently. Mother thwarted all attempts by her husband to teach her to drive, but she quietly picked up knowledge to operate the camera, which she would pass on to my older brother when he would come of age, and later me. Her daughters, at that time, were happier in front of the camera.

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

There is an album earmarked for my father’s office photographs taken by commercial photographers in various cities for the Bombay-based company he worked with. It was very likely inspired by my grandfather’s album of official photographs from his days at Lahore Electricals, the first power plant in Lahore set up not long after the power plant from the Delhi Durbar was used to provide electricity to a few houses in Delhi. All these images are of strangers, not just to me, but many even to my siblings, and of strange places, that was to me the outside world. These two albums embody the family’s arc of modernity that neatly coincides with the larger longing for modernity in Asia. First in pre-Partition, colonial India, in my grandfather’s association with public modernizing endeavors funded by local rather than foreign capital, went on to define our lives beyond his lifetime. Then as part of the family’s post-Partition rehabilitation through its earlier association with the nascent industrial ventures in Lahore – many of these would translocate to Bombay at the time of Partition – that were now spurred by Nehru’s call for new temples of modern India. The same thread my father picked up in Independent, post-Partition India, when my father bought the Ricohflex to affirm his faith and desire to be part of the larger modernity of Nehruvian India.

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

These albums are now the ones I can easily pick up and peruse for they reveal larger histories in which both my grandfather and father played roles. There is a near silence that envelops them and makes them as interesting as photographic histories: objective, factual, and detailed. These albums announce the presence of the other in the family archive. Though many images in them of strangers could never “cross the boundaries of difference the family asserted,”[9] these unknown men and women promised me the world.

***

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

The family albums now are in shambles, the photo corners remain on the sheaves of photo albums. The photographs are misplaced. There is no way they can ever be reinstituted in their original spots. The albums bloat with these loose images. The original chronology organizing the images and their implied narratives has unraveled. Maybe now the photo archive is at its most stable state. Freed from these strictures of timelines, the archive might be more ready to be reimagined. What remains of this photo archive for me, beyond its slowly deteriorating material reality, is their affective existence as voices. Voices as a larger sensorial experience, what Taussig calls, “a barely conscious mode of apperception and a type of ‘physiological knowledge’ built from habit.”[10] More than the photo albums’ ordinary affect, their “varied, surging capacities to affect and to be affected…give everyday life the quality of a continual motion of relations, scenes, contingencies, and emergences,” it’s the memory of that unremarkable affective mutuality that persists.[11] Maybe, the archive has served its scaffolding-like purpose, helping the family continue its search for modernity. While I worry about its fate, the family photo archive might already be dreaming of going into the world to socialize and lose itself in its cacophony.

_____

[1] Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 3

[2] Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of The Black Radical Tradition, University of Minnesota Press, p. 210

[3] Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy or The History of Photography Part, Stanford University Press, 2015, p. 141

[4] Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 10

[5] Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses, Routledge, 1993, p. 26

[6] Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of The Black Radical Tradition, University of Minnesota Press, p. 210

[7] Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After Holocaust, Columbia University Press, 2012, p. 1

[8] Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 11

[9] Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 48

[10] Michael Taussig, Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses, Routledge, 1993, p. 26

[11] Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects, Duke University Press, 2007, p.

Copyright © 2022, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Hemant Sareen is an independent writer, editor and photographer based in New Delhi. He writes on modern and contemporary art, photography and the moving image. He was also a contributing editor and an associate editor for Art Asia Pacific magazine. Recently, he designed and taught global humanities courses titled Globalization and Photography and Global Cultures of Exhibition and Viewing at Ambedkar University in New Delhi. He is the contributing editor for Ranbir Kaleka: Moving Image Works (Kerber Verlag, 2018). As a photographer, Sareen has appeared since 2012 in group shows including the 2018 FotoFest Houston’s India focused exhibition, INDIA: Contemporary Photographic and New Media Art.

Copyright © Hemant Sareen

Copyright © Hemant Sareen

20 November