Old magazines, Elvis vinyl records and songs of the legendary Googoosh. As a child I grew up with these references from my mother’s childhood at our house in Wazirabad. But it took a pandemic for stories to be shared and memories to be rekindled. My mother’s family lived in various cities of Iran for short periods from the 1940s to the 1960s. Her father, Abdul Hameed Irfani, called ‘Papaji’ by the entire family, had walked out of his village barefoot to become the Cultural Attaché in the Pakistan Embassy in Tehran. When and how Papaji taught himself photography, from composing fabulous frames to developing his own pictures, nobody knows. But along with his Ikoflex camera, Papaji was to document the idyllic life of his family during this period. Papaji was a scholar of the Farsi language and was passionate about the poetry of Rumi and Iqbal. He even became a bestselling author of books on this subject. A generous teacher and coach, his amenable nature made him a popular figure amongst the locals. My Nani Ami (grandmother), Fehmida, adapted well to the busy social engagements marked in the weekly schedule. At the same time, she raised six children, Kalim, Naim, Tanvir, Nahid (who is my mother), Mansoor, and Suroosh, besides hosting a continuous stream of Iran’s cultural icons at her house.

The Irfanis, four brothers and two sisters, still retain a deep bond (Naim passed away from cancer in 2008) and reunions in Lahore are an annual event. In 2020, like everyone else in the world, the siblings could not meet. Meanwhile digging through locked up cupboards in Wazirabad, my sister Huma discovered a trove of old albums, an archive of the family in a long-vanished era. Young Arfan, whose father Mukhtar has driven the family car for years, was entrusted with the task of scanning these photos to preserve them. This brings me to the Irfani WhatsApp group.

In the early days of the lockdown, when the group was abuzz with handwashing videos, it struck me that sharing one photo a day from the family archive would not only keep everyone’s spirits up but also trigger memories and generate stories behind the photos. And so, another kind of reunion took place as the siblings annotated the photos with stories, memories, secrets, and details which added layers to the images. The pictures triggered sensory memories and at times a recollection of experiences that were not even in the picture. The siblings often filled in the blanks for each other. These photos shared on the WhatsApp group became a doorway through the pandemic and into the vastness of a commonly remembered childhood.

Some of them are being shared below.

Payendeh House, circa 1950 (from L to R): Tanvir, Nahid (with cat), Naeem (sitting), Mansoor (on cycle), Kalim and the youngest Suroosh. Nani Fehmida in the background.

The family moved homes several times before the partition in 1947 when Pakistan was created. Despite Papaji being a Farsi scholar, he made sure the family spoke Punjabi at home. The houses they lived in are still remembered by their Punjabi names like Lal Ghar (Red house), Pay’endeh Ghar (Perennial house) or Chitta Ghar (White house). All Iranian homes have a pond in the courtyard and this location has served as the backdrop to many of the photos. Papaji has made sure that the children are arranged like props in compositions that show their Eid clothes clearly. My Nani in white at the back looks over from the distance.

Tanvir: This photo is from Payendeh Ghar, Tehran.

Mansoor: Papaji had gone on some official duty to Baghdad and on his return, he brought this tricycle that I am riding in the picture.

Kalim: We all used to take turns riding on in circles around the ‘hauz,’ the pool!

Tanvir: Naeem was in primary school so he had to shave his head every week!

Suroosh: Look at the French blinds of the basement across the courtyard. These housed the spacious rooms of our house help as well as the kitchen where Tanvir and Kalim once stapled two parts of a broken 78 RPM record by pressing it with gramophone needles heated on the stove. I wonder if Kalim or Tanvir remember that?

Kalim: I remember the experiment! The results were pretty good as we could not afford to keep buying new records!

Mansoor: We had a dog whose name was Farang and he was reddish brown in color. I wonder if the cat’s name was Maloose?

Nahid: The cat I’m carrying is different from Maloose.

Tanvir: The other cat was called Muchhan vali (Punjabi for ‘Mustachioed’).

Naeem (with Muchhan vali) and Suroosh, 1959

Naeem (with Muchhan vali) and Suroosh, 1959

The legendry Muchhan vali, a beauty with a black moustache makes an appearance in a playful photo of Naeem and Suroosh. Naeem wears a regional Iranian cap, whereas Suroosh has an empty box of books on his head and his belt hangs loose. The boys often took liberties with the Ikoflex, taking silly photos without permission. This picture may have been taken by Kalim. Apparently, such photos were given their own labels by the children and called ‘Hasde Khaid-de’ (‘fun and games’ in Punjabi).

Muchhan vali with Pepsi bottles, circa 1959

Muchhan vali with Pepsi bottles, circa 1959

In another photograph Muchhan vali snuggles up with another cat and we see a big empty bottle of Pepsi in the background. A photo of the kids holding glasses of the drink triggers the following exchange.

Mansoor: Great picture. We were enjoying our Pepsi-Colas in the Tehran Museum. Papaji used to detest the beverage. He called it synthetic and always recommended Nimboo pani (lemonade).

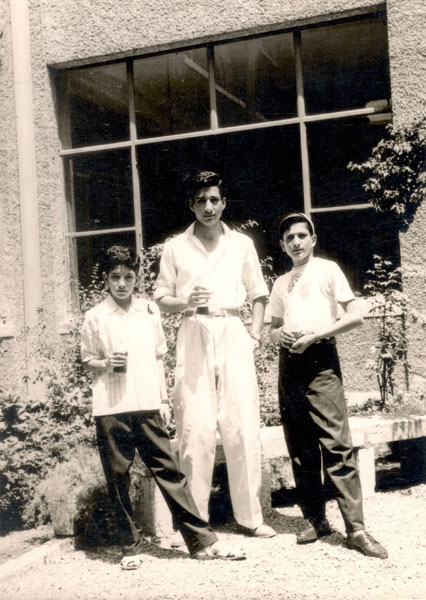

L to R: Suroosh, Naeem and Mansoor, 1956

Suroosh: The curator of the museum was a stunning Shirazi beauty (I only learnt after that she was from Shiraz) called Maheen Tavalleli. When we went on our great road trip to Shiraz in 1960, Maheen Khanum invited us all for dinner to their house. I still remember that when leaving, she told Ami (mother) after shaking my hand, “I think he has fever.” She was right. I was running high fever all the way back. I remember that one of Papajis ‘saintly’ friends in Esfahan sent “Aab e Nebat” for me to our hotel. This was water dipped with crystalline sugar-stem blown with healing verses. Unfortunately, though, this sweet gesture was ineffective, and I kept suffering.

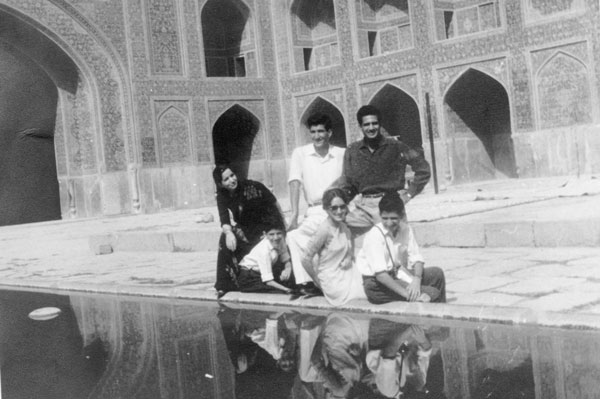

Esfehan, 1960 (L to R): Nani Fehmida, Suroosh, Nahid, Mansoor (sitting) Naeem and Kalim (standing)

Of course, while everyone remembered the ‘Shirazi beauty’, nobody remembers the name of the pious friend from Esfahan. But we found another family picture taken around a hauz in the Masjid e Shah, now called Masjid e Imam in “Esfahan… nisf e jahan” (a well-known Persian saying that means, “To see Esfehan is to see half the world.”)

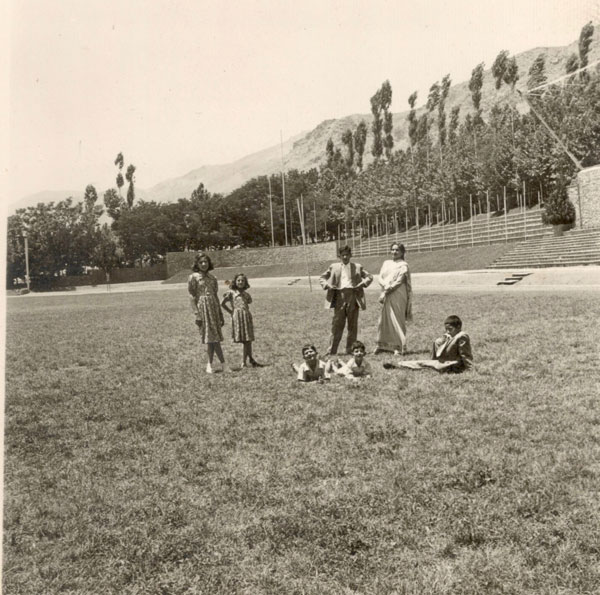

Visit to Manzarieh, early 1950s (L to R): (standing) Tanvir, Nahid, Kalim, Nani Fehmida

(on ground) Mansoor, Suroosh, Naim

The Esfehan photo is from a road trip taken in the sixties in the fin-tailed Plymouth Desoto which was the rage at the time. Before that, childhood trips consisted of going to scenic spots close to the city.

Mansoor: I think this ground used to be used for holding scouts jamboree.

Kalim: It was probably the Amjadieh stadium.

Suroosh: Manzareih. A different world altogether, higher up in the foothills of the Elborz mountains. Its ground had that exclusive feel of majesty and rarefied air. I don’t know if anyone remembers the brand, new red cricket ball and bats and new yellow wickets, which looked so massive to me at age five. This was part of Papaji’s unsuccessful attempt to introduce cricket that sunny day. All that I remember is that he was wearing cream trousers and shirt, and bowling the shiny red ball with a smile … I have no idea who was at the wickets!

Mansoor: I remember the new, red shining cricket ball and the smell of varnish.

At this point my sister Huma couldn’t help but comment “Your recollection in such detail – is rather unnerving – I can’t even recall where I put my keys this morning!”

Suroosh: Well, Huma, recollection of the past and the question of memory can be quite tricky. I may have a vivid memory of distant events in the past, but when it comes to the present, sometimes I can’t tell whether or not I took the medicine I was supposed to after meals! It’s perhaps no different from forgetting where you put your keys!

In some ways memory remains something of a mystery. In the 1970s, Dr. Penfield, a neurosurgeon at McGill University found that when certain parts of the brain of some of his patients were stimulated with electrodes, the patients’ recall of distant memories, including childhood, was astounding. They recalled even the smells and sounds of the moment, like Mamu Mansoor did in recalling the fresh varnish of the brand-new cricket ball when he was six.

As for Dr. Penfield, it remains a mystery as to why some people had such vivid recall of the past, as if they were actually reliving that moment when a part of their brain was stimulated, while others remained indifferent.

In any case, childhood memories are often enduring, and that’s why Papaji virtually knew by heart whatever he read of Rumi and Iqbal, and that remained with him to the very end!

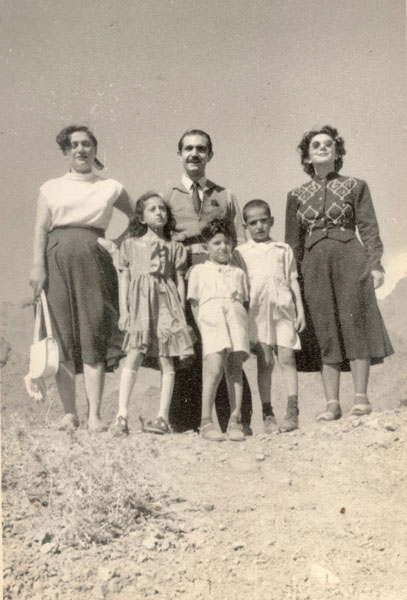

Aamanieh Hill, 1952 (L to R): (Adults) Amelia, George, Dr.Kazimi (Kids) Nahid, Suroosh, Mansoor

The memory of Papaji was associated with sports for a reason. He not only taught himself tennis (being from a very humble background he used a ball made of rags), but also turned into a fantastic coach eventually rubbing shoulders with Iran’s royal family on the courts.

Nahid: I remember after our first visit, we kept wanting to go back again. However, the nearest we got there was a visit to another hilltop.

Suroosh: In this picture I think we are standing atop the Amanieh hill with Amelia and her husband George. Both of them were Armenians and very close family friends.

Nahid: George was a very handsome man. Amelia very kind and soft.

Kalim: Dr. Kazimi’s mother was Russian, she was our closest family friend.

Nahid: Dr. Kazimi was an angel in human form. I remember she gathered all the bones when she came for dinner and distributed them to stray dogs on the streets. May she rest in peace.

Suroosh: Mansoor and I are not too happy with the sun; though Nahid seems quite content with her reddish-pink taffeta frock which had a beautiful ‘Phumman’ (frill) in front!

Kilosh Frocks, 1954: Tanvir and Nahid (sitting on floor)

Nahid: Our outfits were always credited to our Ammi ji and her astute eye and taste of what was proper and appropriate.

Tanvir: Yes she was amazing. A woman, who took care of six children, with Papaji and throwing grand parties. She also knitted and tailored. The dress we sisters are wearing was made by her, God bless her. It was Eid in Tehran.

Nahid: She was always content and full of gratitude. My dress was red and gold and Tanvir’s golden and cream.

Tanvir: The cut of these frocks is called ‘Kilosh’ in Farsi (Persian).

Nahid: They are cut on the bias like Lehngas.

Manuchehri School, 1951: Nahid in 4th row right

The black and white of the pictures does not stop my mother’s memories from flooding back in Technicolor. Here she is seated on the floor with her sister Tanvir, their dresses spread out for full effect, to display the designer skills of Nani Ami.

Mansoor with the mandatory shaven head for primary school, remembers the names of the schools, which leads to an interesting passage.

Tanvir: Nahid in fourth row.

Mansoor: This looks like Dabestane Manuchehri. I studied there and in Ferdowsi in the early ’50s, perhaps ’52 to ’55, before we moved back to Pakistan.

Nahid: I don’t remember when this photo was taken. It has vanished from my memory!

Kalim Irfani: I too went to Manuchehri and had a most wonderful young Math teacher who for the first time opened my eyes to start comprehending the mysteries of the subject for the rest of my life! I will always remain indebted to him.

Tanvir: Dabestan e Manuchehri was at walking distance from our Pa’yendeh house in Tehran.

Kalim Irfani: At the Pa’yendeh house during the time of the overthrow of Mossadegh, I remember seeing plumes of smoke of bombs going up in the city center and southern Tehran.

Mossadegh, the only democratically elected Prime Minister in Iran who nationalized oil and was overthrown in a coup. As the family lore goes, Papa ji had visited him when he was in power and recited a verse that he had greatly appreciated. Later at Mossadegh’s trial he found it hard to look at him standing in the dock.

Lal Ghar, 1949 (L to R): Nani Fehmida, Shirin with baby, Kalim, Suroosh (carried by Rajab Ali),

Lal Ghar, 1949 (L to R): Nani Fehmida, Shirin with baby, Kalim, Suroosh (carried by Rajab Ali),

Mansoor (hands in pockets), Nahid, Naim, Tanvir, Batool Khanum (extreme right)

The beautiful reflections in the ‘hauz’ in the Esfehan photo above are visible in a number of photos. Clearly, Papaji noticed these and the hauz was one of his favorite spots to take pictures. But nothing could have prepared one for the stories that emerged from the above photo.

Mansoor: Is the lady on extreme right Batool Khanum? If yes, she was the wet nurse who breast fed me in Mashhad as Ammi was weak and unwell.

Tanvir: Yes, she had a newborn son your age.

Mansoor: I remember around this time, Batool Khanum was lactating and would entertain us kids by letting out a stream of milk to our amazement and enjoyment.

Nahid: I had completely forgotten Batool Khanum’s unique entertainment. That is very funny!

Kalim: The man at the back might be Rajab Ali who was probably, Ali Asghar’s brother, who died long ago in a roof collapse during heavy snow fall around Mashhad, close to Tehran. Both used to recite Rostam o Sohrab’s epic story (this was from the Persian epic Shahnameh written by Firdowsi in the 10th century) often. I was very fascinated by the tragic battle between father and son, and Rostam realizing too late that he had killed his own son Sohrab. That used to make me very sad!

The ‘missing’ photographer from the above pictures, Papaji, finally makes an appearance in photos most probably taken with a self-timer. He was self-taught.

Kalim: Like with cricket, Papaji was a compulsive ‘teacher,’ and he did the same with photography. He always emphasized the importance of the aperture and shutter speed (in those earlier days of analog photography) and of course a precise focus and the overall frame of the ‘subject’!

Unknowingly we absorbed many of his instructions to develop an eye for photography.

Papaji Irfani, mid 1950s

Papaji Irfani, mid 1950s

Garden, 1952 (L to R): (Back row) Nani Fehmida, Tanvir, Naim, Kalim (Front row) Nahid, Suroosh,

Mansoor (with Papaji’s empty frames)

Mansoor: Papaji used to replace his own glasses with this empty frame without lenses to avoid light being reflected from them. I seem to be making good use of them now in the pandemic when we are all on the screen!

Kalim: I remember those ‘fake’ glasses. They usually came handy for occasions when he was being photographed! Mansoor loved them too as a child!

Mansoor is wearing the same empty frame glasses in the picture of all six children with their mother.

Papaji Irfani and Nani Ami Fehmida, 1959

Papaji Irfani and Nani Ami Fehmida, 1959

Mansoor: The painting on the wall is the artist’s depiction of a Rubai written by Papaji, a few verses of which that I recollect are “Nagahan az asman amad farood, Dilbari zeba tar az bood o nabood, Ismay oo az bahr e man Iran bowad, Ism e janan khobtar az jan bowad”. (In a blink she descended from the heavens, A beauty beyond description, For me her name is “Iran,” The name of one’s beloved is more precious than one’s own life.)

Nahid: “Ishq ra hafsad par ast va her parri Az faraz e arsh ta teht al sara.” (Love has seven hundred wings and each feather goes from the earth to the limits of the sky.)

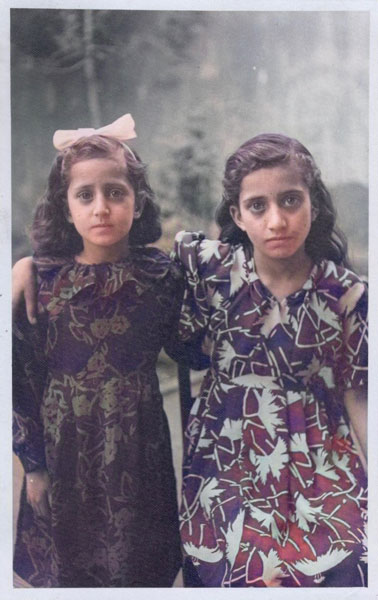

Nahid and Tanvir, 1948

Nahid and Tanvir, 1948

And a final twist to the WhatsApp tale. When the picture above was shared, I decided to put the vivid Irfani memory to test: ‘What were the colors of the frocks?’ To which my aunt Tanvir responded, ‘Can’t remember but not black.’ On a whim, I put the picture through a colorizing app and posted the result. The reaction was electric.

Nahid and Tanvir, 1948 (Re-colored, 2021)

Farjad: The computer thinks these were the colors!

Tanvir: The computer is right!

Suroosh: Whatever the computer thinks, it has certainly made a great creative leap over the decades and brought to life the colors of life in their infinite diversity!

Mansoor: Wow wow!

Nahid: Speechless!

In the late sixties the family returned from Iran to Pakistan. On an ill-fated night a thief broke into the house and made away with a few suitcases. One of them had all the film negatives of Papaji’s life’s work. The Irfani siblings still shake their heads in dismay recalling this enormous loss, but they did continue with Papaji’s training in their own way. My own fledgling attempts at photography got a boost when my mother taught me readymade formulas of f-stops and aperture for outdoors and indoors using her Minolta to get some amazing results.

As I write these words, the realization strikes me that it was exactly twelve months ago that the pandemic forced us to share these photos. In the end, the green eyes of my mother and aunt in the colorized picture, staring at all of us in innocence is a befitting end to this journey. For a brief moment we have all shared the same living, breathing past.

Copyright © 2021, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Farjad Nabi was invited to write this essay for PhotoSouthAsia by our Guest Editor, Sabeena Gadihoke. We encourage you to begin with Gadihoke's introduction, The Family and the Self in the Time of the Pandemic, and to also read Gadihoke's other invited essayists:

Sohail Akbar: Two Archives

Surayanandini Narain: Home Reimagined: Photographic Archives of 2020

Copyright © Farjad Nabi

Copyright © Farjad Nabi

Farjad Nabi is a Lahore based writer who learned the basics of photography on a vintage Yashica using 120mm film. Looking back, the ten exposures that film roll allowed were much more deeply satisfying than the unlimited clicks he takes on his smartphone nowadays. He trained in the developing and printing of black-and-white film at the National College of Arts, followed by a stint as a photo journalist for various publications, including Himal South Asia. Nabi ventured into the moving image with the experimental film Nusrat has Left the Building…But When? His debut feature film is Zinda Bhaag, co-written and co-directed with Meenu Gaur. As a playwright Nabi has written a number of stage plays in Punjabi.

20 November