Located on the outskirts of erstwhile Bombay in Thane, every weekend in the late eighties, my parents ritually took us to the neighborhood theater that customarily staged Marathi plays from different parts of Maharashtra. I would enthusiastically wait for the curtain to rise – an elaborate handmade tapestry that would unravel a plethora of stories. The cool breeze from the air-conditioning and the well-lit stage made the entire experience of viewing riveting, but instead of the performances, I started observing set designs, the way walls of a make-believe home with its cardboard cut-out windows peered into a fictitious outside. It is here that I got intrigued about the relationship between the inside-outside and the manner in which these make-believe worlds were built.

Here, the proscenium frames a narrative. What intrigues me is the staging of a narrative, the frame in which a plot is set, where the background doesn’t just remain as a backdrop but carries an ideological charge. Where the mise-en-scène transforms itself into a conceptual framework, as is vividly noticeable in the film Stalker (1979; Andrei Tarkovsky), that pierces deeper into the Soviet architectural unconscious [1]. Filmed in a disused and rotting power station, which becomes the zone [2], it portrays a forbidden landscape where the Stalker leads a writer and a scientist in pursuit of the hidden truth. The decaying concrete tunnels, fetid pools, dilapidated bunkers, and peeling walls of a perishing socialist society provide an instant iconography of a dreadful impending future. The last scene is premonitory – the Stalker with his family walk on a muddy beach in front of a nuclear power station that looks like an intimation of the Chernobyl disaster that was to befall six years later.

Place is a geographical entity, that can be reflected upon through imagination, envisioned either within this world or located somewhere in outer space, or as a site within a psychological map of one’s mind; it can be drawn through references and cues from history, mythology, or memories. When laced with nostalgia, it can denote longing; yearning can imply distance or suggest dislocation and displacement either by choice or force. Alienation is often a result of such movements. But then what is homelessness? Is it a condition of our time where we are all refugees or even tourists in transit, in-between, neither here nor there? Ever uncertain of our location?

For a solo show titled Local Time at Experimenter, Kolkata in 2012, I tried to draw upon the notion of time in relation to a place. The Russian literary critic, Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975), articulated the notion of time and space in his concept of the Chronotope [3] as “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature.” What intrigues me is “how our sense of self and history, is also a sense of our time and place” rooted in specificity. For Two Points of View (2012), I collaborated with an artist-friend Dhrupadi Noor from Kolkata to document (through a series of photographs) the sky from Kolkata and Mumbai, to underline the unobserved time lag that exists between the two states. Commencing from sunrise in Kolkata to sunset in Mumbai, we photographed the sky hourly from the same spot in the hope to build some kind of an indiscernible link between the two vantage points, through the act of gazing and documenting it was an attempt to make an inscription through time and place.

A photographic documentation of the sky from Mumbai and from Kolkata

on 9.9.2012 from 5:27 am to 6:48 pm; Photographs of the Mumbai sky courtesy Prajakta Potnis;

photographs of the Kolkata sky courtesy Dhrupadi Wahshat Gosh.

The self and the human body find recurrence as a site of engagement and exploration throughout art history. Furthermore, feminist art managed to subvert representations of the idealized female body as an unquestioned motif in art. The practice of speaking the unspeakable of making visible that which should remain hidden has been central to a lot of twentieth century feminist art. Mona Hatoum in Corps étranger (1994) [4] sent a camera literally exploring the mysterious insides of her body. The video was projected onto a gallery floor in a small cylindrical structure accompanied by heart murmurs and breathing sounds confronting the viewer directly; the video installation [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qsci0WAd_Lk] manages to subvert the objectifying heterosexual male gaze turning the inside out while consecutively tackling the subject of surveillance to an extreme level of invasiveness.

The thought of a foreign substance colonizing and disrupting lives has concerned me ever since I saw my mother’s terminated uterus full of fibroids, lying on a petri dish next to her hospital bed. An unwarranted growth that had stealthily infested her body without leaving any evidence of it outside, left me perturbed. I started to ponder over the fragility of our body and it being vulnerable to imperceptible elements. In Porous Walls (2008), I explored the idea of contamination within everyday domestic objects that seemed to have given to outgrowths and resultant decay; I used mustard seeds and beads to signify these outgrowths gradually taking over our lives as these hyperobjects [5] laid patiently on meticulously carved granite platforms that were reminiscent of a domestic kitchen.

(detail) from The Porous Wall series, plastic beads and mustard seeds

(detail) from The Porous Wall series, plastic beads and mustard seeds

adhered onto found objects, carved granite platforms on metal stands,

dimensions of each platform: H26.5″ x W24″ x L 46″ (2008)

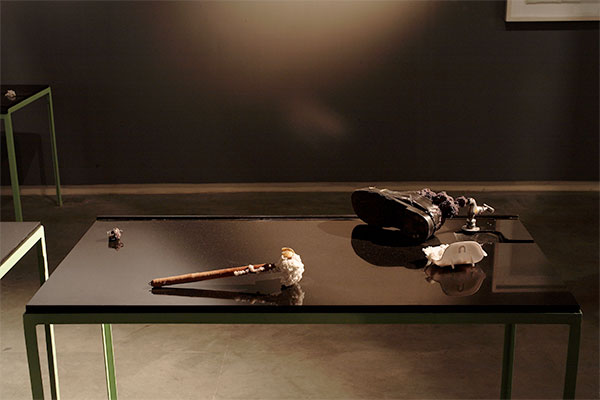

(detail) In a Body Without Organs (2020)

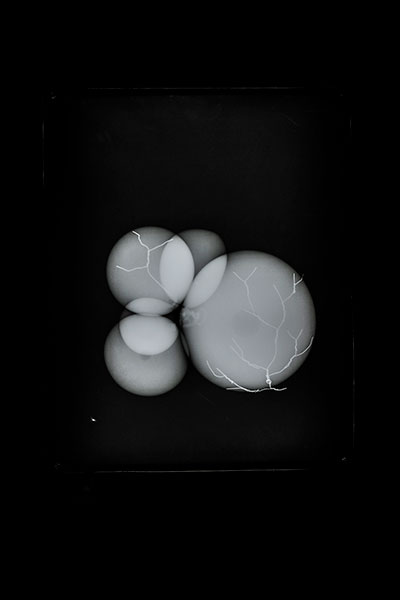

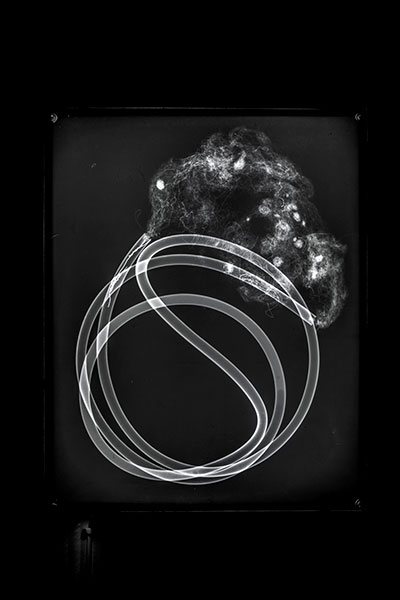

At Project 88, Mumbai, I contemplate on an overburdened laborers body in relation to a capitalist state. A series of works within the show, titled He Woke Up with Seeds in His Lungs (2019-2020), are a set of X-ray films seen through backlit light boxes of found objects constructed or sculpted together to resonate a body or an organ that turns host to a foreign element. Interior vistas of the body appear as electromagnetic rays passing through various tissues and surfaces creating abstracted form of the mundane familiar object. The process of developing X-rays is quite similar to developing films in a darkroom – images slowly appear as the film gets exposed, unlike a painting where an image is built through the process of layering paint. The idea of exploring the medium of radiology came to me while researching and rummaging through some chest X-rays of a family member who had suffered lung infection from working in a soap factory for life.

He Woke Up with Seeds in his Lungs 6,

He Woke Up with Seeds in his Lungs 6,

X-ray film in LED light box, 12 x 15 inches (2020)

It is critical within my practice to assert the voice of an individual, to reflect on how top-down policies affect a life. In an attempt to negotiate through the socio-political minefield vis-a-vis the personal, the domestic space takes on the role of a protagonist. The cavities of everyday domestic appliances with their sterile interiority exudes a sense of other worldliness, which could also be a result of the materials and technologies developed mainly as war inventions. It is interesting to observe their percolation within the realm of the domestic and especially the kitchen. This helps, I believe, to bridge the otherness divide by turning the social concerns into a deeply personal inquiry.

He Woke Up with Seeds in his Lungs 6,

He Woke Up with Seeds in his Lungs 6,

X-ray film in LED light box, 12″ x 15″ (2020)

The inside of a refrigerator, for example, a sterile temperature-controlled space that expands time by delaying the process of decay. Its captivating light has a sense of the familiar and is reminiscent of the inside of a mall or an airport where the sense of time and place is suspended indefinitely. These “non-places” as Marc Auge [6] calls them, follow a certain kind of archetype as the inside of these sterile spaces exuberate an antiseptic character that is disconnected from the local / outside. The anodyne and anonymous solitude of these non-places offers the transitory occupant the illusion of being part of some grand global scheme: a fugitive glimpse of a utopian city-world.

Escalators, a visibly common feature in these non-places offer the experience of automating and catalyzing the process of arriving, leaving, ascending, or descending. In a time capsule of departures, arrivals, and travels, all the strangeness is somehow to be withheld by the characteristic homogeneity of these spaces designed to camouflage the alienation that globalization is suspected to bring along.

Capsule I, Light box with aluminum frame, 72″ x 120″ (2018).

Collection of The Bhau Daji Lad Museum and Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

Capsule III, Print on hahnemuhle bamboo paper, 37″ x 60″ (2012)

In an attempt to transform the site of the freezer into a space that could resonate a corporeal site of a memory bank, I keep returning to an interview of Boris Groys where he states, “… memory functions as a freezer …” Is it possible then, to actually sculpt or carve a physiological scape? By appropriating found film slides from the personal archives of an unknown tourist (that I unearthed in a quaint market in Berlin in 2014), I hoped to travel back in time to the various sites visited by this tourist. By projecting these found landscapes onto the walls of the freezer, I tried to open up one of the walls to create a space within a space, and in some instances carve a window within this enclosed environment quite similar to the wallpapers of snow clad mountains found in living rooms of middle class homes especially in the early 1990s. These are images of elsewhere, these unattainable landscapes that could have been only reimagined through memory. By freezing them, I am hoping to go back in time, in a naïve attempt to conserve these sites from aging.

Zone, Light box, 9″x 12″ (2018)

[2] https://strelkamag.com/en/article/post-stalker-notes-on-post-industrial-environments-and-aesthetics

[3] Chronotope: In literary theory and philosophy of language, the chronotope is how configurations of time and space are represented in language and discourse.

[4] Mona Hatoum Corps étranger http://www.newmedia-arorg/cgi-bin/show-oeu.asp?ID=150000000007761&lg=GBR

[5] https://muse.jhu.edu/book/27131

[6] https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100237780

https://mu.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/153-159-Prajakta-Potnis-Reading-an-Art-Show.pdf

https://www.firstpost.com/long-reads/opening-door-prajakta-potnis-6880181.html

Copyright © 2022, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Prajakta Potnis was invited to write this essay for PhotoSouthAsia by our Guest Editor, Sharbendu De. We encourage you to begin with De's introduction, Against Capturing - in a World of Ideas, and to also read De's other invited essayists:

Ravi Agarwal: The Entangled Image

Soumya Sankar Bose: Where an Improbable Reality Meets Fiction

Photograph © Prajakta Potnis

Photograph © Prajakta Potnis

Prajakta Potnis has extensively shown her works since 2001 nationally and internationally. Her solo shows include: A Body Without Organs and When the Wind Blows at Project 88, Mumbai (2020; 2016), Kitchen Debate, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin (2014), Local Time at Experimenter, Kolkata (2012), Membranes and Margins at Em gallery, South Korea (2008) and Time Lapse, Porous Walls and Walls in Between at The Guild Art Gallery, Mumbai (2008, 2006).

In 2018, she participated in Facing India: India at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg. Her work was part of A Tripoli Agreement curated by Renan Laru-an in collaboration with Air Arabia and The Sharjah Art foundation. She won the Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Grant for Photography (2016-17). Her works have been exhibited in the 11th Gwangju Biennale (2016) curated by Maria Lind, Kochi -Muziris Biennale (2014) curated by Jitish Kallat, Kadist Art Foundation, Paris and Clark House Initiative, Mumbai. In 2011, her works were part of the travelling exhibition titled Indian Highway IV, Mac Lyon Museum of Contemporary Art Lyon, France, Indian Highway III at the Herning Museum of Contemporary Art, Denmark (2010) and Indian Highway II at the Astrup Fearnley Museum, Norway (2010).

Her selected biographies include: Facing India, Ed. Ralf Beil, Uta Ruhkamp (Hatje Cantz, 2018), Store in a Cool and Dry Place (Verlag Kettler, 2015) supported by KFW Stiftung and Kunsterhaus Bethanien, I’m Not There: New Art from Asia ed. Cecilia Alemani (The Gwangju Biennale, 2010), Younger than Jesus: Artist Directory co-published by Phaidon Press Limited, London and New Museum, New York (2009).

20 November