Photography is simultaneously the documentary evidence and the archival record of such transactions. Because the camera is literally an archiving machine, every photograph, every film is a priori an archival object.

~ Okwui Enwezor, 2008[1]

Traumatic events fuel memories for present and future generations, creating the material for archives that build human history. In the context of the Jewish Holocaust, Marianne Hirsch has written extensively on remembrance being aided by photographic archives of survivors.[2] She has called this “postmemory” referring to memories that are transferred via images to those who have not actually witnessed the trauma. The COVID-19 pandemic confronts us with the possible loss of a massive potential archive from the year, 2020. Yet, it has also created the circumstances for postmemory in the making where the image archive of this moment is poised to inform the future of the traumas suffered today. As such, photography has responded urgently, even as the pandemic has cloistered every photographer, other than the press employee, under global lockdown. The figure in charge of visually documenting this transformation has been reminded of her own vulnerabilities as she too stays home, described by one as a “bird whose wings had been clipped.”[3] Physical mobility, so far inalienable to the practitioner’s operational reality, lies suspended.

Even as the SLR lies unused and gathers dust, the Smartphone and webcam have offered new opportunities for photography that are congruent with the current condition of stasis. The slowing of time and motion has allowed for an alternative image archive to emerge, which collates the interior rather than the exterior domain for its subject matter. The video call and the WhatsApp photos taken on the hand-held phone camera have allowed access into homes and private spaces, and into lives that were secondary to a fast-moving, extrovert world. Dissemination of imagery on digital fora has enlivened new networks of knowledge, empathy, and action. This essay looks at virtually available photographic works by Sumiko Murgai Nanda and Maryam Eisler that comprise the growing archive of pandemic imagery. It takes into account images produced by them during the summer of 2020, which have developed into online projects. Their locations in different parts of the world is immaterial to their work, which has taken shape entirely online. Towards the end of the essay, their archives are contrasted with a tangible photographic exhibition by photographer-artist Moutushi Chakraborty, which preceded the COVID breakout in India by a matter of weeks. Given that all three photographers address the idea of home and family in times of transformation, a foregrounding of medium and contexts of reception provides intriguing comparisons of images from what will be a historic year for humanity.

Mediated by digital technologies, it is suggested that postmemory has transitioned into ‘connective memory,’ where digital networks of viewership help build alliances. Andrew Hoskins dwells on the ‘connective turn’ that memory has taken in the digital age. Along with José van Dijck, Hoskins argues that in the digital realm, memory is neither collective nor re-collective, but is instead structured by digital networks, and constituted “through the flux of contacts between people and digital technologies and media.”[4] Memory, they argue, is constituted not only through individuals and social institutions, but also through technological media such as digital photography and its virtual networks. Given that COVID-19 has urged state authorities everywhere to implement lockdowns, the idea of visualizing home has indeed become connective, albeit varied in the actual manifestations of lived domesticities and uneven access to technologies.

Much like a still version of the Netflix original short films series titled Homemade, photographers everywhere have culled narratives that in these changed times refer to an unseen present and a transformed future.[5] The home has always been there, but we did not live like we do now. This juxtaposition of past / present has been of interest to imagemakers such as Sumiko and Maryam. Describing her current predicament of being a photographer under lockdown, Sumiko, a professional fashion photographer who undertakes personal projects in the genre of street photography, has conceived a visual project titled Coro – equalizer with portraits of people from affluent backgrounds as they isolate from the world in their homes.[6] In this ongoing project she has virtually documented more than 40 families globally. She regards this as a collaborative project, as these people, mostly first-time acquaintances, share their transformed lives under lockdown through the arrangement of a photographic portrait. Together with Sumiko, the families stage themselves over a Zoom or WhatsApp call while being directed by her in using gestures, postures, and settings that best express their experience of the lockdown. Vogue magazine first published this work online on its Instagram account.[7]

Photo: Sumiko Murgai Nanda

Photo: Sumiko Murgai Nanda

Sonia and Hamid, Portugal. Coro-Equalizer: my phone project, 2020

Photo: Sumiko Murgai Nanda

Photo: Sumiko Murgai Nanda

Jose, Mexico. Coro-Equalizer: my phone project, 2020

Photo: Sumiko Murgai Nanda

Photo: Sumiko Murgai Nanda

Tikari Family, Gurugram. Coro-Equalizer: my phone project, 2020

In a similar project, British photographer Maryam Eisler looks at her favorite artists under lockdown in the series titled: Confined Artists – Free Spirits: Photographs from Lockdown for the latest issue of Lux magazine.[8] Each portrait is accompanied by an individual reflection on the lockdown rather than articulating familial adjustments. Having recently concluded this project with 163 artists from over the world, Maryam has devised a visually dense archive and a collaborative practice to explore inner worlds / minds in a moment of crisis. These professionally diverse, upper middle-class subjects use digital technology and the wide frame to look inwards in more self-reflexive ways as they perform rituals of the everyday, rather than engaging with the world outside. In contrast, Maryam’s artists appear in a standard format, tightly framed by the camera, excluding all but the artist’s own figure. They reflect on matters of global importance beyond the home, such as the concurrent political event of the Black Lives Matter movement. In fact, their domesticity has little to do with family, and more to do with individual vocality as they articulate poetic responses to the pandemic.

Maryam Eisler, 2020.

Tom Sachs. Series: Confined Artists – Free Spirits: Photographs from Lockdown. First published in LUX Magazine.

Maryam Eisler, 2020.

Fahamu Pecou. Series: Confined Artists – Free Spirits: Photographs from Lockdown. First published in LUX Magazine.

Maryam Eisler, 2020.

Shirin Neshat. Series: Confined Artists – Free Spirits: Photographs from Lockdown. First published in LUX Magazine.

Interestingly, the works of both photographers have been shown in online fora for publications like Lux and Vogue that focus on an elite lifestyle indicating that even home, or indeed picture-worthy domestic living, is a luxury. Such archives exist on the internet alongside many other bodies of work that focus on the less privileged. Among these were press photographs that tracked the exodus of migrant workers towards rural India, as they grappled with reaching ‘home’ and staying ‘safe’ during the pandemic. Another online exhibition, titled Through Her Lens and supported by Zubaan and the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, featured the work of several women photographers who sought to portray feminine preoccupations with domesticity in the northeastern states of India. The images were stark, drawing attention to incremental labor, lack of leisure, and the overwhelming materiality of domestic innards during the pandemic.[9] As Enwezor articulates in the epitaph to this essay, every photograph anticipates an archive to be built in retrospect to the event in question, all the while keeping the future in mind. The archives of 2020 collapse these temporal differences, as event, image, and reception take place instantaneously over the digital medium. COVID-19 is perhaps the greatest humanitarian crisis to have hit the world since the invention of the internet, and its archival presence has hence been novel too. People across the world suffering under the uneven unfolding of the pandemic have made themselves visible to the camera as digital networks of communication have penetrated deeply. There is a blurring of the public and the private realms in the virtual space, even as the pandemic seeks to physically harden the same lines. We have entered homes and met families which otherwise would have remained distant and yet these remain virtual dialogs unaccompanied by the physicality of travel or tactility. The aforementioned photographers and their projects have growing archives on multiple online fora that have taken shape because of our unusual circumstances – and may actually change once the virus has been arrested.

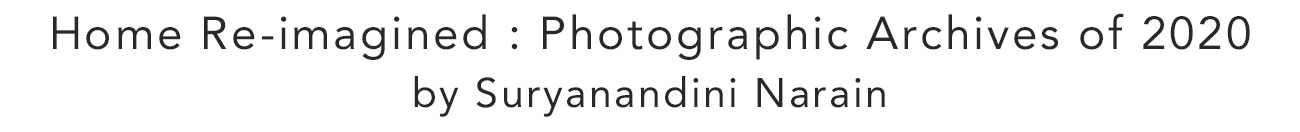

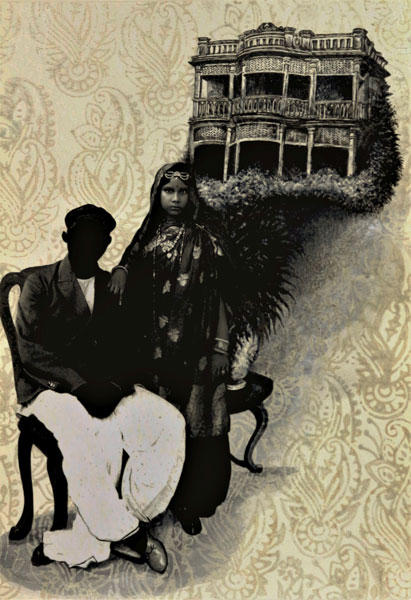

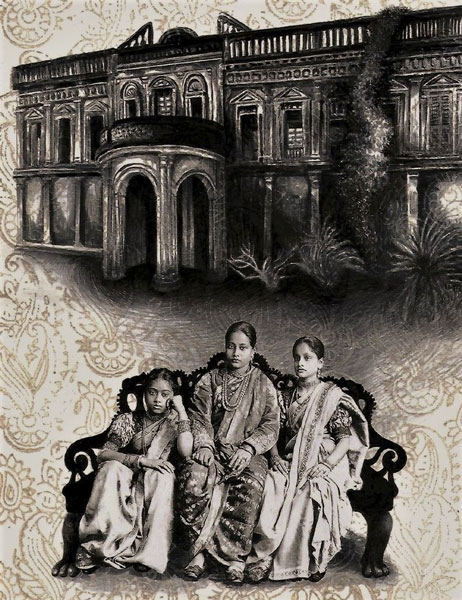

What might 2020’s photographs have looked like had the virus not appeared? Would the images have been fresh or repetitive, working within the same genre classifications as they always have? Has mobility indeed been the enabler for photographic imagination or is that an overstatement when it comes to the subject of home, rooted in physical and metaphorical stasis? I would like to conclude with a brief discussion of an offline exhibition that was shown a few months before the pandemic. Moutushi Chakraborty’s photographic series, The Homeland, was exhibited at the India International Centre in New Delhi between the 24th of December 2019 and 3rd of January 2020. As one of the final pre-pandemic photographic exhibitions in New Delhi, it tapped an alternative imaginary of home, displacement, and loss. Moutushi’s archive imagined a lost homeland from pre-Partition Bangladesh. The artist did not travel to the land of which she inherited second or third generation postmemories, but reconfigured found images of her family and strangers in fictional tableaus. Moutushi embellished orphaned images from forgotten histories with paint, thread, and charcoal, thus recasting them against homes imagined for them. The Homeland is an archive in the imagination of an author who chooses to stay put, while rearranging visual elements such as people, buildings, items of everyday use, on the material surface of the image. The trauma of the Partition of 1947 lurks on the edges of these frames, a horror only anticipated or experienced by the photographed subjects, internalized and archived by those who feel the aftershocks of displacement, such as the artist herself. Her work is suggestive of the kinds of archives which COVID-19’s impact may create decades later, photographically and otherwise, through the frameworks of postmemory and connective memory. This remains a body of work with heightened materiality, flagging the beginning of a year that would see a marked transition into virtual photographic exhibitions.

Moutushi Chakraborty

Moutushi Chakraborty

Homeland 2. Collage, ink, and acrylic on Fabriano paper, 9×11 inches

Moutushi Chakraborty

Moutushi Chakraborty

Homeland 8. Collage and acrylic on Fabriano paper, 9×11 inches

Moutushi Chakraborty

Moutushi Chakraborty

Homeland 12. Collage, thread, ink, and acrylic on Fabriano paper, 9×11 inches

Moutushi’s rearrangement of visual elements – such as the colonial bungalow, the woman in a Brahmika sari, the block printed background, and the toy rocking horse – is in the form of a collage. The intervention occurs postproduction – manually, digitally, and from within the image domain, as existing archival material is reconfigured into new narratives of desire. On the other hand, Sumiko’s placement of people, pets, furniture, and the phone camera as a viewing device has taken place at a pre-photographic moment. She directs her subjects into positioning themselves and their paraphernalia, communicating their situation through a tableau of familial intimacy. Time works in different ways for either photographer, but the pastness of Partition in Moutushi’s work, or the ongoing pandemic informing Sumiko’s work have an equal sense of palpability. Both archives foreground the photographer’s agency, inflecting the frame with her version of how families should or could or wish to appear. The opening up of the home is envisaged by Moutushi as toys, patterned wallpaper, and family postures outside the bungalow facade, while Sumiko’s phone camera zooms into the drawing rooms and bedrooms of her subjects, as they eat, work, exercise, and relax. While Moutushi marks her images with artistic interventions of the brush, in Sumiko and Maryam’s works the presence of the photographer is made literal, as their own faces appear to peer through ‘windows’ on the screen, framed along with their subjects. There is an intricate intersection of gazes between the photographer, subject, and unseen viewer in these frames, as if caught mid-sentence and in dialog with each other. The individuals and families in Sumiko and Maryam’s works wish to be seen, inviting viewers into their personal realms, hoping to be archived for remembrance at a time when accelerated mortality at the hands of COVID-19 has mercilessly reduced lives to a mere statistic. Finally, what is the nature of communication with which these points of visual participation are entrusted? In Maryam’s words, “it is my hope, that these images and accompanying poetry, reveal very personal, delicate and emotional moments; honest and forthright, direct and inspiring, intermingled with the pain of sorrow borne by each one of us, for threats new and unforeseen. But most importantly, it is my sincere belief that these are messages of hope and renewal.”[10]

__________

[1] Okwui Enwezor, “Archive Fever: Photography between History and the Monument,” published with the exhibition Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, International Centre for Photography, Steidl, 2008

[2] Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Post Memory, USA: Harvard University Press, 1997

[3] Sumiko Murgai Nanda, artist’s statement shared privately, May.2020

[4] Andrew Hoskins, “Media, Memory, Metaphor: Remembering the Connective Turn,” Parallax, Nov.2011. Hoskins and van Dijck refer to Maurice Halbawch’s definition of “collective memory” (1925) as the knowledge which can be constructed, shared, and passed on by large and small social groups.

[5] Homemade on Netflix comprises the work of 17 well known filmmakers responding to COVID-19 with short films on the experience of self-isolation. First episode: 30.Jun.2020

[6] www.instagram.com/p/CBphJ9yBAkj/

[7] www.instagram.com/p/CBphJ9yBAkj/?hl=en, 20.Jun.2020

[8] www.lux-mag.com/confined-artists-free-spirits-2020/

[9] It might be worthwhile here to make a brief reference to another online exhibition organized by the royal family in Britain in collaboration with the National Portrait gallery. Titled “Hold Still”, the show sought to re-imagine relationships under lockdown, all within a somewhat effulgent positivity that was timed with the then decline in viral cases in the UK, as people began to leave home for work, travel and leisure. The contest was open to the public, and the best 100 images were selected by a panel headed by the Duchess of Cambridge. The intention behind archiving or indeed museumizing the images of this project was to depict the indomitability of the human spirit, but ironically it also seemed to deny the sense of grief that naturally accompanies trauma.

[10] Maryam Eisler, 10.Apr.2020, London; www.lux-mag.com/confined-artists-free-spirits-2020/

Copyright © 2021, PhotoSouthAsia. All Rights Reserved.

Surayanandini Narain was invited to write this essay for PhotoSouthAsia by our Guest Editor, Sabeena Gadihoke. We encourage you to begin with Gadihoke's introduction, The Family and the Self in the Time of the Pandemic, and to also read Gadihoke's other invited essayists:

Sohail Akbar: Two Archives

Farjad Nabi: 700 Wings of Love

Photograph © Suryanandini Narain

Photograph © Suryanandini Narain

Surayanandini Narain is Assistant Professor of Visual Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her doctoral thesis addressed the feminine figure in family photographs from Delhi. A recipient of scholarships from the Ford Foundation, INLAKS and ICSSR, Narain has also been involved as an assistant editor for various volumes of Marg. She teaches courses on Indian visual culture, photography, aesthetic theory and critical writing. Narain also has M Phil and Doctoral research students working on graphic novels, digital feminism, documentary photography, queer theory and bazaar art.

20 November